2 MB

Key Takeaways

- The resurfacing of “reverse Kissinger” thinking underscores Washington’s search for leverage, but today’s conditions differ sharply from the 1970s: there is no exploitable Sino-Russian rift.

- Moscow and Beijing are bound by systemic cooperation, joint defense projects, space navigation integration, intelligence sharing, and energy interdependence, which elevate their partnership to historic levels.

- Despite sanctions, Russia sustains trade with China through shadow fleets, barter, yuan-based settlements, and dual-use imports, signaling the rise of alternative financial and technological supply chains.

- For the U.S., pursuing Moscow risks heavy concessions on Ukraine and NATO while undermining trust among allies in Europe and the Indo-Pacific.

- The central strategic dilemma is whether Washington can counter a consolidated Sino-Russian axis without destabilizing its alliance architecture — the foundation of U.S. global influence.

In today’s geopolitical reality, the United States faces a key security challenge: the strategic rapprochement between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation. The partnership between these two countries covers vast territories in Eurasia. It possesses enormous resources and military capabilities, including strategic nuclear weapons, posing a direct threat to the national interests of the United States in the Asia-Pacific region. Therefore, some American experts are considering repeating the success of a similar case, the Soviet-Chinese split of the 1970s. This would prevent excessive rapprochement between the two countries by applying a strategy known as the “reverse Kissinger,” which involves bringing the United States closer to Russia as a counterweight to the greater threat posed by China’s rapid growth in power.

In the context of the US-China confrontation, repeating the success of Kissinger and Nixon by dividing the two Eurasian continental powers seems quite attractive and even necessary, given the weakening role of the West in world politics. However, in today’s reality, adapting Henry Kissinger’s approaches to Russian-Chinese relations is ineffective and risky. Unlike in the 1970s, Russia and China now have the closest ties in history, as evidenced by their close economic, military, and technological cooperation, as well as joint anti-American diplomacy. The US is unable to offer Moscow benefits that would replace its support for China, and concessions to the Kremlin would threaten to destroy the allied security system.

Why Kissinger’s Historical Precedent Will Not Work

First, it is worth understanding the essence of the US-USSR-China triangle in the early 1970s.

Back in the 1960s, relations between the USSR and the PRC underwent a deep crisis due to the conflict between Mao Zedong and Nikita Khrushchev, which resulted in a border skirmish on Damansky Island (1969). Against the backdrop of the Cultural Revolution and deteriorating relations with the USSR, China itself began to express interest in rapprochement with the US.

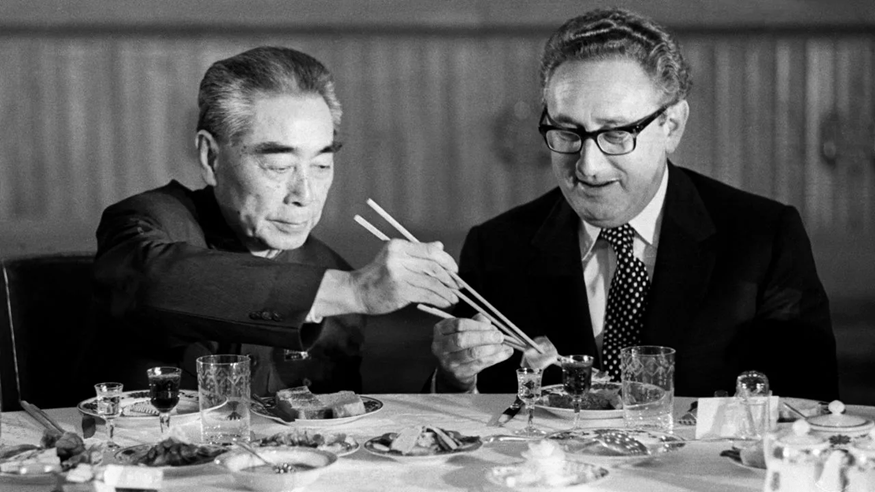

In 1972, the Nixon administration, seeking to prevent the formation of a Eurasian communist bloc, initiated a rapprochement with the PRC, which gave the US additional leverage in its relations with the USSR and, after 1979, led to US-Chinese defense cooperation against the Soviet threat. Kissinger believed that it was always better for the United States to “be closer to either Moscow or Peking[1] than either was to the other.”

In the 1980s, the opening of the Chinese economy provided foreign companies with access to a market of about 900 million consumers and a large, cheap labor force. By creating Special Economic Zones with tax breaks, customs preferences, and simplified procedures, the PRC attracted large-scale investment and production relocation, resulting in significant profits for international businesses.

Kissinger, effectively taking advantage of the existing Soviet-Chinese split, made a successful geopolitical maneuver at the time. His triangular diplomacy opened China to American and international business and created an important partner for the United States in countering Soviet influence. Today, Russian-Chinese relations demonstrate the synchronisation of strategic goals, so there is no internal rift that Washington can exploit.

The Current State Of Russian-Chinese Relations

After the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and Western sanctions, Russia made a so-called “turn to the East.” The contours of this policy were outlined in 2019 in a collection of reports entitled “Towards the Great Ocean” (К Великому Океану) by the Valdai Club, a leading Russian think tank closely linked to the ruling elite, which shapes and articulates the Kremlin’s key foreign policy narratives. Given Asia’s growing role in the global economy and politics, the authors noted the need for Russia to actively integrate with Asian markets, diversify its foreign trade, and participate in regional initiatives. They also highlighted China’s key role as the main driver of Russia’s “turn to the East” and its role in supporting the Russian economy amid Western sanctions. In general, this concept positions Russia as a Euro-Atlantic-Pacific power capable of maintaining its status as a great power in the 21st century through a balanced model of Russia’s global presence and active participation in shaping a new political and economic order in Asia.

The Diplomatic Duo Of Moscow And Beijing

Since 2022, there has been a noticeable intensification of cooperation between Moscow and Beijing. On February 4, 2022, 20 days before the invasion, Putin visited the Chinese leader in Beijing, where a joint statement on “International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development” was published. In this statement, Russia and China presented themselves as dominant world powers. The parties also condemned the expansion of Western-led multilateral institutions such as NATO and AUKUS. At the same time, the countries emphasized the importance of expanding institutions where they have significant influence, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and BRICS. Russia and China utilize the latter to promote new international payment systems and trading currencies, aiming to weaken the dollar’s dominance. The countries announced the creation of a “partnership without borders” and the pooling of efforts to counter the American liberal order.

At the UN, these countries often act as allies, as neither has vetoed a resolution initiated by the other. In most cases, China either supports Russia or abstains from voting on issues that Russia vetoes. Over the past 20 years, Beijing and Moscow have disagreed on voting only once – in November 2024, when Russia blocked a resolution on a ceasefire in Sudan, which China, on the contrary, supported.

On March 21, 2023, during Xi Jinping’s visit to Moscow, the leaders of the two countries signed a joint statement on “deepening comprehensive partnership and strategic cooperation entering a new era,” which defined the level of Russian-Chinese relations as “the highest in history.” China’s diplomatic support for Russia was demonstrated by the Chinese leader’s visit to the parade in Moscow dedicated to the anniversary of the end of World War II on May 8-9, 2025. During the parade, the leaders of both countries promised to counter the influence of the United States. The next meeting is scheduled for September 2025 in China during a parade marking the end of World War II, to which Beijing has announced plans to invite US President Donald Trump.

Given such a high level of political interaction, cemented by numerous strategic agreements, coordinated positions on the international stage, and personal trust between Xi and Putin, the likelihood of a significant political rift between Moscow and Beijing seems extremely low.

Economic Support Despite Pressure

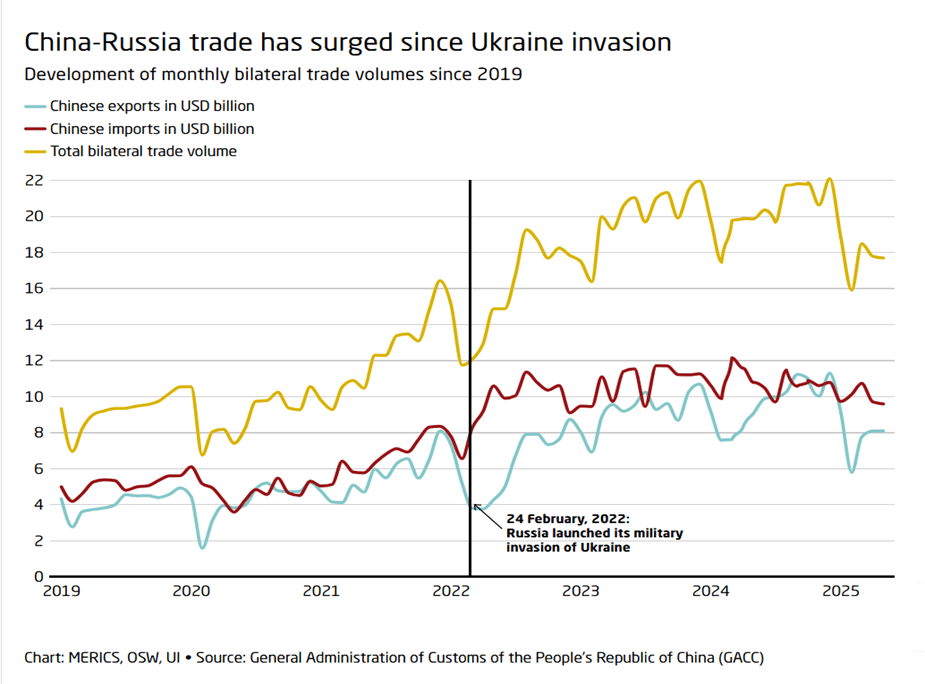

Trade between the countries grew by about a third in 2022–2023, reaching a record high of over $235 billion, and remained at a historic high even despite a slowdown in growth in 2024 due to Western threats of secondary sanctions for cooperation with Russia.

Russia’s energy sector dominates its exports, particularly to China. China has become the largest importer of Russian oil, replacing Europe as the main buyer of the commodity. Crude oil accounted for almost half of Russia’s exports to China in value terms each year from 2021 to 2023. The total value of mineral fuel exports from Russia to China increased significantly between 2021 and 2023, accounting for the majority of Russia’s total exports to China, indicating the growing dependence of Russian energy exports on the Chinese market.

At the same time, Russia accounted for only 19% of China’s crude oil imports, as China prefers to diversify its suppliers (for this reason, Beijing is postponing approval of the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline proposed by Russia). However, due to significantly reduced prices for Russian energy resources, the Russian Federation remains the largest exporter of oil to China, which supports its economy in the context of the exhausting war against Ukraine. Despite Washington’s demands and threats to impose 100% tariffs on Chinese goods, China refuses to stop importing energy from Russia, thereby demonstrating strategic solidarity with Moscow.

China’s exports to Russia also increased after the invasion, but are more diverse. China exported $72.7 billion worth of goods to Russia in 2021, about half of which were electronics and machinery. In 2023, this amount increased to $110 billion, mainly due to the automotive industry: sales of cars, trucks, and other types of transport from China to Russia increased more than fourfold in three years. The vast majority of these imports are ordinary consumer goods or industrial machinery and components. At the same time, Russia actively uses dual-use products supplied from China, such as electronics, machinery, and civilian vehicles, for military purposes in Ukraine.

Therefore, it can be argued that economic cooperation with China, despite the asymmetry, it supplies the Russian population with consumer goods, sustains the economy with critical finances, and equips the military with essential technologies for waging war against Ukraine.

However, economic cooperation is still far from being a “boundless partnership.” International sanctions have complicated China’s economic support for Russia. Three of the four largest state-owned banks in China and 98% of local Chinese banks began to refuse financial transactions in yuan with sanctioned Russian institutions after the US announced in December 2023 that it would impose secondary sanctions on financial institutions that facilitate trade with Russia. Since January 2025, Chinese state-owned oil companies have reduced imports of Russian oil due to concerns about secondary US sanctions against the Russian energy sector.

Although Western sanctions have had a significant deterrent effect on the activities of Chinese companies and financial institutions, Moscow and Beijing are still finding ways to circumvent Western sanctions. Russia uses a so-called “shadow fleet” — the practice of transferring Russian oil from sanctioned tankers to non-sanctioned tankers that deliver cargo to Chinese ports. Some Russian oil companies use cryptocurrencies to smooth the conversion of Chinese yuan into Russian rubles, as well as gold, avoiding the use of the dollar. Large Russian banks have created a netting payment system called “China Track” for transactions with China, with the aim of mitigating the risks of secondary sanctions. According to Reuters sources, Russia and China may have started using barter trade, which will allow them to circumvent payment problems, reduce the visibility of bilateral transactions by Western regulators, and limit currency risk.

Thus, it can be argued that Russian-Chinese economic cooperation is extremely beneficial for both sides, and the states seek to maintain it even despite Western sanctions. Under these conditions, the US has no tools to replace the Chinese market and technological support for Moscow without destroying its own sanctions regimes and accepting the geopolitical ambitions of Moscow and Beijing.

Military Cooperation Amid Global Tensions

China has become Russia’s key partner in the military-technical sphere, especially after 2014 and the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. According to EU Special Envoy David O’Sullivan, about 80% of components for the Russian defense industry come from China or Hong Kong. According to US intelligence, in 2023, 90% of microelectronics and nearly 70% of machine tools used by Russia were of Chinese origin.

In January 2025, a journalistic investigation by the Schemes project (Radio Liberty) showed that China had become the largest, and in some cases the only, supplier of critical minerals needed for the production of drones and missiles, such as gallium, germanium, and antimony, which are under Western sanctions. A significant portion of the suppliers is linked to state structures and the CCP. The investigation found that among the main Chinese suppliers of critical chemicals to Russia is Yunnan Lincang Xinyuan Germanium Industry, whose main shareholder and chairman is CCP member Bao Wendong. On January 15, 2025, the US State Department imposed sanctions on Wafangdian Bearing Company, a Chinese state-owned enterprise that allegedly supplies bearings to the Russian transport company Tascom. Cooperation with China is becoming critical for the Kremlin amid high demand for resources in the war against Ukraine and the depletion of the Russian defense industry’s potential.

The countries are also deepening cooperation in the development of weapons. According to Bloomberg, Russian and Chinese companies are developing a strike drone similar to the Iranian Shahed. In September 2024, Reuters, citing sources in European intelligence, reported that Russia was building a factory to produce long-range strike drones in China. According to sources, IEMZ Kupol, a subsidiary of the Russian state-owned arms company Almaz-Antey, has developed and conducted flight tests of a new model of the Harpy-3 (G3) in China with the help of local specialists, which Russia used to attack Ukraine’s military and civilian infrastructure.

The PRC is also actively assisting the Russian Federation with intelligence information. According to US intelligence, China is providing Russia with geospatial intelligence data that is being used both in the war against Ukraine and to monitor NATO troop deployments in Europe. The Russian Ministry of Defense is cooperating with the Chinese companies HEAD Aerospace and Spacety.

China and Russia are also deepening their cooperation in the space sector. In 2022, the Russian space agency Roscosmos and the China Satellite Navigation System Commission signed an agreement on “ensuring complementarity” and synchronization of satellites between the Russian GLONASS system and the Chinese BeiDou system. Improvements in the accuracy and coverage of GLONASS and Beidou could reduce global dependence on GPS, undermining the economic and political influence of the US. The satellites of both systems are also critical for the reconnaissance and navigation of military platforms, from aircraft carriers to ballistic missiles. With their help, China will be able to more effectively determine the location of US aircraft carriers and more accurately target them in the event of a potential conflict, posing a significant threat to US global military security.

In addition, in September 2022, Russia and China signed contracts to deploy Russian GLONASS stations in China and Chinese Beidou stations in Russia, underscoring their deep strategic trust. China benefits from technology exchange with Russia in its desire to surpass the US in space, which will improve the military capabilities of both countries in opposition to the West. Moscow is also interested in cooperating with China in space exploration, especially in light of its failures, as further evidenced by the agreement on joint work on the exploration of the Moon and the creation of a lunar base.

In addition to providing resources, equipment, and technology, the parties conduct regular joint military exercises. The cooperation is based on the “Roadmap for Military Cooperation for 2021-2025” signed in November 2021. It provides for the intensification of strategic exercises, joint patrols, and contacts between the defense ministries of both countries and highlights the strength of the partnership between Moscow and Beijing. Since its signing, the countries have conducted at least 31 joint exercises, including multilateral maneuvers with Iran called “Maritime Security Belt.” In May 2022, the countries conducted a 13-hour joint patrol involving bombers over the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea during then-US President Joseph Biden’s visit to Tokyo for a Quad coalition meeting. This move can be seen as a response by the Russian-Chinese bloc to the strengthening of the US regional partnership with countries in the Indo-Pacific region.

Russia and China also participated in joint naval and air exercises “Northern/Interaction” (2023, 2024) and “Joint Sea” (2022, 2024, 2025) in the Sea of Japan and the East China Sea. In July 2024, the countries conducted their first known joint patrol of strategic bombers with two Tu-95s and two H-6s near Alaska in July 2024, briefly crossing the Alaska Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ).

An analysis of these facts shows that military-technical and intelligence cooperation between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation is strategic and goes beyond situational cooperation. Its systematic, comprehensive nature and coverage of critical areas, from the supply of components for the defense industry and joint development of weapons to the integration of space navigation systems, exchange of intelligence data, and regular large-scale exercises, indicate the formation of a stable security partnership infrastructure. This model of cooperation aims not only to enhance mutual defense capabilities but also to create a long-term counterbalance to the United States and its allies.

Prospects For A “Reverse Kissinger” In Today’s Reality

Why Moscow Will Not Choose Washington

Under these conditions, Moscow is not interested in rapprochement, as the potential benefits of warmer relations with the US do not outweigh the costs of distancing from China. Russia is currently demonstrating increasing dependence on Chinese technology, markets, and military cooperation, which Washington cannot offer in exchange for breaking ties with Beijing. The United States will not replace Chinese contracts for Russian energy, as the country exports more oil than it imports. Western sanctions, despite the possibility of being eased by the Americans, will not be lifted completely due to the position of the Europeans, and US-Russian military cooperation seems impossible due to Russia’s hostility towards the US and and Washington’s lack of interest in Russian military technology.

The United States is unable to offer Russia an alternative equal to Chinese support, which makes the idea of a Russian-American rapprochement strategically unattractive for both sides. Under current conditions, Russia receives from China what the US cannot provide without a substantial revision of its principles: stable economic cooperation despite sanctions, technological and military collaboration, diplomatic cover on the international stage, and, most importantly, acceptance of Russia’s ambitions in the post-Soviet space along with assistance in undermining the global role of the United States itself. Moscow is unlikely to side with the United States in containing China, as it has too many reasons for close cooperation with it.

The US cannot provide Russia with such benefits without destroying its system of alliances in Europe and Asia, which would make any strategic rapprochement extremely costly and politically toxic. Even if Washington were to consider such a scenario, the level of trust between the parties after decades of confrontation, numerous conflicts, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine does not allow for a stable partnership. Thus, given limited resources, conflicting interests, and a deep lack of trust, neither side has a pragmatic incentive for strategic rapprochement.

In addition, the United States is a democratic country where the president is elected every four years and one-third of senators are elected every two years. With this structure of power, US foreign policy could change dramatically with the arrival of a new president who could return to a confrontational course with Moscow. In contrast, Communist China and Putin’s Russia have a rigid vertical power structure that promotes trust between the two leaders. In addition, the CCP’s course is much more stable. With the start of Xi Jinping’s unprecedented third term as head of state, Putin’s view of China as a more reliable partner (including in countering American influence) is confirmed, as its leader also tends toward centralization and usurpation of power in the country.

A possible rapprochement with Russia will require significant concessions from the United States: partial lifting of sanctions, restrictions on military aid to Ukraine, and recognition of Crimea’s “Russian status” of Crimea to the restoration of NATO’s 1997 borders (which the Russians demanded even before the full-scale invasion as security guarantees), when the alliance did not yet include the states of Central Europe. This would mean de facto recognition of Russia’s sphere of influence in Eastern Europe. However, such concessions are insufficient to satisfy Russia’s demands and “pull it away” from China.

First of all, such concessions do not take into account the profound nature of the Sino-Russian strategic partnership, which is based on the desire to reformat the international world order, in the formation of which the United States played a key role. By launching a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia has decisively demonstrated its desire to change the balance of power in the international arena, in which the People’s Republic of China actively supports it, giving Russia confidence in continuing its policy. Sino-Russian cooperation is fully in line with the interests of both countries in their desire to undermine what they see as the excessive influence of the United States. In addition, the Chinese energy market is key for Russia, and the level of military cooperation and the volume of dual-use goods supplies force Russia to remain close to Beijing.

Such flirting with Russia may also be perceived by other actors as a weakness of the US and the West as a whole, which will increase the risk of aggressive actions by Beijing against Taiwan, encourage Russia to test the strength of NATO, and prompt other local actors to push back against American influence in their regions.

Strategic Risks Of The “Reverse Kissinger”

Furthermore, such a policy would destroy trust in the United States as a reliable security partner both for the world at large and for its allies. For NATO members, as well as Indo-Pacific partners such as Japan, South Korea, and Australia, Russia’s concessions will be perceived as the US’s willingness to trade the security of others for illusory strategic gains. This, in turn, will raise concerns among US allies about the willingness and ability of the US to defend their security in the face of external threats, undermine transatlantic unity, and may even lead to restrictions on cooperation (for instance, cessation of intelligence sharing or denial of access to foreign military bases for US military forces).

Moreover, reaching significant compromises with Moscow could lead US allies to believe that Russia is capable of pursuing its aggressive goals and is willing to expend significant resources to do so. Such a signal weakens confidence in the steadfastness of US support and encourages partners to reevaluate their strategic orientations. As a result, this may contribute to a tendency toward a more flexible policy toward Moscow and Beijing, even if such a policy is contrary to US interests.

Replacing time-tested alliances with an attempt to establish cooperation with Russia, which is characterized by instability and unpredictability, is certainly not a policy of realism in the spirit of Kissinger. For decades, the US alliance system has been based on trust and commitments that have stood the test of time: NATO has ensured the security of Europe, while alliances with Japan, South Korea, and Australia have ensured stability in the Asia-Pacific region. Instead, the US risks undermining the trust of those who have supported international stability for decades.

The idea that Russia is capable of replacing or even becoming an alternative partner in this system contradicts the available facts. The Russian Federation has repeatedly demonstrated itself to be an unstable actor: the annexation of Crimea, the war against Ukraine, and nuclear blackmail — all of this has demonstrated Russia’s role as a destabilizer of the international system. Moreover, even those countries that are formally considered its “allies” do not receive adequate support from it. Moscow did not provide substantial assistance to Iran during the US attack on Iranian nuclear facilities, despite the expectations of the Iranian side, or to Armenia, a member of the CSTO, in the new round of conflict with Azerbaijan.

Therefore, focusing on Russia as a potential strategic partner seems unfounded and short-sighted, as it undermines the fundamental principles of proven allied relations, ignores Moscow’s destructive role in the international system, and involves satisfying its geopolitical ambitions at the expense of US interests. Such a strategy could deal a significant blow to the international prestige of the United States as an influential global actor, causing a gradual decline in its role on the world stage and significantly limiting its ability to influence the behavior of other states to realize its national interests.

Conclusion

In the current environment, the “reverse Kissinger” is a risky strategy with high costs and minimal chances of success. The Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China are united not by temporary circumstances, but by a shared vision of a world order without US dominance. The United States, in turn, cannot replace China in providing Russia with support at such a level, which makes Russian-American rapprochement unprofitable for both Russia and the United States. Therefore, exchanging long-standing allies for an unstable and unreliable partner is not a manifestation of pragmatism, but rather a dangerous illusion that ignores the realities of the 21st century.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations with which the authors may be associated.

This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. It’s content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.