2 MB

Key Takeaways

- Russia’s Hybrid Warfare: Moscow uses hybrid tactics, including sabotage, cyberattacks, and airspace violations, to test NATO’s resolve while avoiding overt conflict.

- Frequent Airspace Violations: Incidents like drones crashing in Romania, Latvia, and Poland demonstrate persistent Russian provocations.

- Sabotage Operations: Undersea cable disruptions, factory fires, and cyberattacks on NATO members underscore Russia’s capacity to destabilize through unconventional means.

- Ambiguity of Article 5: NATO’s collective defense mechanism is unclear when addressing hybrid threats.

- Member States’ Readiness: Some nations are already taking steps to bolster defenses, including increased military spending and legal frameworks for countering airspace violations.

- Fragmented Responses: The lack of a unified NATO strategy, further compounded by Donald Trump’s ambivalence toward collective defense, places the burden on individual member states and raises concerns about the Alliance’s credibility and long-term deterrence capabilities.

On October 19, 2024, an unidentified flying object was spotted above Romania. On the same night, Ukraine suffered yet another attack by Russia, with Moscow having launched around 98 drones and six missiles in an attempt to weaken the critical infrastructure of Kyiv. This incident comes just one day after a similar occasion on October 18, when targets were detected in the Romanian airspace during another attack by Russia. Even though the objects tend to disappear from the radars before Romanian forces can detect their origin, the happenings of the Russian-Ukrainian war just one border away suggest that most likely, they belong to Moscow.

This is just one example of many – for Romania and other NATO member states. Suspicious flying objects were seen above Germany, an aerial vehicle reported to be Russian crashed in Latvia, and two Belarusian helicopters violated Polish airspace. Even though many of these incidents are brushed off as ‘not intentional,’ they are a warning sign that the Russian threat to NATO might be more serious than it is generally believed.

Countering security threats is a cornerstone of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation, and its founding treaty has a mechanism to support it – namely, Article 5. However, with the limited occasions of its invocation and fears of the Russian-Ukrainian war escalation, it is still unclear whether it will be triggered should the conflict spill over the Ukrainian borders – and whether NATO members even believe it must be. Moreover, in an era where hybrid threats increasingly challenge traditional security paradigms, questions arise about NATO’s readiness to counter them. This article aims to analyze what exactly Article 5 implies, in which cases it can be applied, whether it is sufficient to address hybrid threats effectively, and how member states treat the possibility of invoking this mechanism against Moscow.

Is Russia Threatening NATO?

It would be wrong to claim that the Russo-Ukrainian war is confined strictly to Ukrainian borders. Even though the direct armed attack on NATO territory hasn’t happened, a report by the U.S. Helsinki Commission Staff suggests that Russia has been waging a ‘covert shadow war’ against the alliance since 2022.

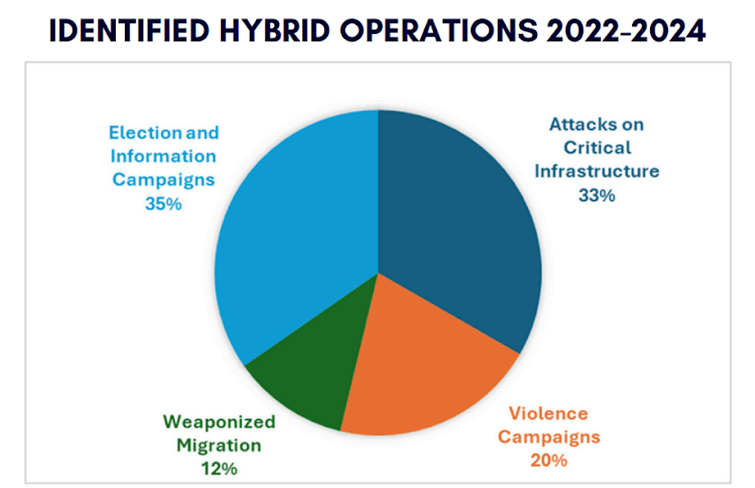

Back in May 2022, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov claimed that NATO was conducting a ‘total hybrid war’ against Russia, apparently comparing Ukraine’s staunch support and sanctions against Russia to hybrid warfare operations. Evidently, Moscow decided to respond to the so-called ‘total hybrid war’ with an actual hybrid war of its own all over the Euro-Atlantic area (see Figure 1).

The report states that there has been a great deal of operations against NATO member states attributed to Russia since 2022. Out of these, about a third were election and information campaigns, and another third were attacks on critical infrastructure. One in ten operations was a weaponized migration campaign (that is, an artificial border crisis), and one in five was a violence campaign (that is, acts of vandalism or terrorism) (see Figure 2). Attacks range from antisemitic graffiti in France and GPS signal disruptions from Kaliningrad to a ransomware attack that disrupted thousands of pharmacies across the US and an attempt by either Russian or Belarussian operatives to bomb a paint factory in southwestern Poland.

Russia is also suspected of being behind some serious sabotage campaigns. These involve a fire in a German factory belonging to defense manufacturer Diehl in Berlin in June 2024 and a fire at one of the largest shopping malls in Warsaw in May 2024. Moreover, in November 2024, the communication cable between Lithuania and Sweden was damaged, reducing internet bandwidth in the area by one-third. Meanwhile, data transmission between Finland and Germany has been completely disrupted due to a similar cable break. That cable was the only direct connection of its kind between Finland and Central Europe, running alongside other critical underwater infrastructure, including gas pipelines and power cables. Both incidents occurred just weeks after the U.S. reported increased Russian military activity around major undersea cables.

Aside from non-traditional threats, Russia (and, at times, Belarus) is also suspected of directly violating the airspace of NATO member states. Some of the cases include the above-mentioned incidents in Romania (with not only unidentified flying objects entering its air, but those identified as Russian, too – including the drone debris crash in Tulcea County), Germany, and Latvia. Some more suspicious occasions can be mentioned, such as the September 2024 occurrence in the Stockholm Arlanda Airport, Sweden. Unidentified drones interfered with the facility, which resulted in planes routed there to change their path and land in other airports. The Swedish police commented that this act might have been intentional, although they ‘cannot answer the purpose.’ Sweden could not identify what flying object it was dealing with, making it problematic to take concrete actions. However, German special services suspect that the drones were the Russian Orlan-10 models, and Latvia went as far as identifying that the object in its air was a Shahed 136-type drone.

And – as if that wasn’t enough – the incidents go even further. In March 2022, the Soviet-era drone (which later turned out to be a TU-141 reconnaissance aircraft) with explosives flew over Romania and Hungary with no reaction from the local forces and crashed in Croatia. It was never confirmed that the aircraft was Russian. According to investigators, there was a red star on its wing painted in blue and yellow, the Ukrainian flag colors. Several months later, in December 2022, Croatian, Romanian, and Hungarian authorities claimed they knew who had launched that drone, but the information was marked as a state secret.

Moscow doesn’t only hold such provocations covertly. Lately, it has been quite explicit in its threats to NATO. On December 16, 2024, Russian Defense Minister Andrei Belousov told the Defense Ministry in a joint meeting with President Vladimir Putin that ‘the Ministry of Defense of Russia must be ready for any development of events, including a possible military conflict with NATO in Europe in the next decade.’ In the same meeting, Putin claimed that the United States, with their ‘weapons and money’ they use to ‘pump the de facto illegitimate ruling regime in Kyiv,’ bring Russia ‘to the red line across which we [Russia] can no longer retreat.’

Russia may not have explicitly launched an armed attack against the territory or forces of NATO countries. This is a smart move – after all, it is complicated to determine whether these provocations fall under Article 5 directly. However, the scope and range of incidents are so broad that the danger they imply cannot be dismissed. With these sabotage activities, Russia appears to be testing NATO. And unfortunately, as long as Moscow doesn’t get an assertive and resolute response, it might take it as a go-ahead to go even further. Right now, its operations might be aimed at causing confusion and showing how far its power and influence can reach. But eventually, upon ensuring no one resists, it might attack NATO more straightforwardly.

Exploring Article 5: Will it Be Enough to Counter the Attack?

Article 5 is famous for its ambiguity which originates in the treaty text itself. The best-known part of the article reads, ‘The Parties agree that an armed attack against one or more of them in Europe or North America shall be considered an attack against them all…’. However, the most important part comes afterward, ‘…and consequently they agree that, if such an armed attack occurs, each of them, in exercise of the right of individual or collective self-defence recognized by Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, will assist the Party or Parties so attacked by taking forthwith, individually and in concert with the other Parties, such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force, to restore and maintain the security of the North Atlantic area’. Thus, Article 5 does not require any member state to deploy its armed forces and immediately strike back. In contrast, the states are only obliged to ‘assist’ the Party or Parties attacked. It is upon member states to determine what the assistance should be – and seeing as the treaty does not provide the exact list, it could mean simply imposing economic sanctions on the aggressor.

Such vagueness was embedded in the founding treaty on purpose. When negotiators were discussing the text of the document in 1948-1949, the United States was hesitant about committing to any military obligations. At the time, many Americans still supported isolationism, which meant not interfering in European affairs.

Additionally, Article 6 further clarifies Article 5. It says, ‘For the purpose of Article 5, an armed attack on one or more of the Parties is deemed to include an armed attack:

- on the territory of any of the Parties in Europe or North America, on the Algerian Departments of France 2, on the territory of Turkey or on the Islands under the jurisdiction of any of the Parties in the North Atlantic area north of the Tropic of Cancer;

- on the forces, vessels, or aircraft of any of the Parties, when in or over these territories or any other area in Europe in which occupation forces of any of the Parties were stationed on the date when the Treaty entered into force or the Mediterranean Sea or the North Atlantic area north of the Tropic of Cancer.’

Therefore, the collective defense mechanism is only triggered when the armed attack has been carried out precisely against the territory of any of the member states or their forces, vessels, or aircraft. Drawing on this wording, the mere act of violating the member states’ airspace by Russian drones does not fall into any of these categories.

Articles 4 & 5 in Action

It is also worth mentioning Article 4, which states that ‘The Parties will consult together whenever, in the opinion of any of them, the territorial integrity, political independence or security of any of the Parties is threatened.’ Essentially, it gives any member state the right to formally invoke this Article by bringing any security issue they find concerning to the discussion table, encouraging other parties to consult.

Unlike Article 5, Article 4 does not imply any commitments other than the need to participate in discussions. Perhaps that is why there have already been seven instances when it was triggered since the beginning of the 21st century. Five of them came from Türkiye, one was initiated by Poland in 2014 as a result of Russia starting a war against Ukraine, and another one resulted in a joint request by Bulgaria, Czechia, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia on February 24, 2022, which were concerned about the full-scale invasion in Ukraine by Russia.

In two cases with Türkiye, consultations ended with NATO agreeing to certain defensive measures, namely Operation Display Deterrence in 2003 and the deployment of Patriot missiles in 2012. Interestingly, the reason for the 2003 instance was the war in neighboring Iraq, and for 2012 – the death of five Turkish residents in the border town of Akçakale because of Syrian shells.

It suggests that Article 4 is even more ambiguous than Article 5. Therefore, much here depends on the political will of the member states and their interpretation of what a threat to security means. After a pretty similar incident happened in Poland in November 2022, the Polish President at the time, Andrzej Duda, excluded the possibility of invoking Article 4. This claim was amplified by the results of the investigation, indicating that the missile killing two Polish residents didn’t belong to Russia but to Ukrainian air defense. ‘There is nothing, absolutely nothing, to suggest that it was an intentional attack on Poland,’ Duda added.

Meanwhile, Article 5 has only ever been invoked once. The request to do so was made unanimously less than 24 hours after the terrorist attacks against the United States by Al-Qaeda on September 11, 2001. NATO did not make a decision immediately. First, they waited to determine that the attacks had come from abroad and fell under Article 5.

In October, after the investigation was completed and the mechanism was triggered, NATO agreed on a package of defensive measures that included two military operations. However, a closer look at the case illustrates the lack of significant obligations under Article 5 quite well. First, in the Eagle Assist operation, an 830-person crew consisted of personnel from 13 NATO countries, while the total number of member states in 2001 was 19. Therefore, some member states did not send forces – and weren’t obligated to do so. Next, it is important to consider that the only time the collective defense mechanism was invoked was when its most powerful and influential member was in danger. This suggests that such a massive move is largely political and thus can only happen if it falls under the national interests of the alliance countries.

NATO’s Response to the Russian Threat: Does it Consider Article 5?

Since 2014, NATO has recognized Russia as a primary threat to its security, marking a dramatic shift from its 2010 Strategic Concept, which emphasized cooperation with Moscow. This change was driven by Russia’s annexation of Crimea and its war of aggression against Ukraine. The 2022 Strategic Concept acknowledges Russia as the “most significant and direct threat” to Euro-Atlantic security, highlighting its use of conventional, cyber, and hybrid tactics, as well as its disregard for international agreements. Despite this, NATO reiterates its commitment to maintaining open channels of communication with Russia to manage risks, prevent escalation, and increase transparency.

It is unclear which ‘channels of communication’ the concept refers to. It could be negotiations and peace treaties – but the issue is that so far, Russia has violated the majority of international treaties it signed. In particular, the Minsk Agreements were neglected by Moscow when it shelled repeatedly at the Donetsk and Luhansk regions – in 2015, they had already been violated more than 4000 times. The Geneva Conventions were dismissed when Russian armed forces engaged in countless war crimes in the war against Ukraine. In 2008, when the ceasefire was negotiated for the war against Georgia, Russia promised to withdraw its forces to the pre-war positions – but failed to fulfill this promise. This tendency doesn’t leave much room for optimism concerning keeping open channels of communication with Moscow.

On the other hand, as the Russian-Ukrainian war hasn’t stopped after two and a half years, NATO leaders’ rhetoric has been less and less optimistic. In December 2024, NATO’s Secretary General Mark Rutte said it was time to ‘shift to a wartime mindset’ because Moscow was ‘preparing for long-term confrontation with Ukraine and with us,’ and member states ‘are not ready for what is coming [their] way in four to five years.’ With this warning, he wanted to emphasize that the alliance needs to ramp up its defense spending significantly because even the 2% mark is not enough. As of now, even that target has not been met by 8 countries, namely Croatia, Portugal, Italy, Canada, Belgium, Luxembourg, Slovenia, and Spain (see Figure 3).

In June 2024, German Defense Minister Boris Pistorius went as far as admitting the prospect of Russia attacking NATO. He noted that while a Russian attack is not likely ‘for now,’ the experts ‘expect a period of five to eight years in which this could be possible.’ He referred to how the 2022 scenario seemed impossible to the West before, but ‘Russia is defying logic’ – therefore, they ‘must be ready for any scenario.’

Finally, in November 2024, German Federal Intelligence Service chief Bruno Kahl spoke at an event of the DGAP think tank in Berlin and said that Russia was likely to build up its hybrid operations and considered Article 5 invocation in response a possibility. He explained, ‘The extensive use of hybrid measures by Russia increases the risk that NATO will eventually consider invoking its Article 5 mutual defense clause. At the same time, the increasing ramp-up of the Russian military potential means a direct military confrontation with NATO becomes one possible option for the Kremlin.’

In his opinion, if Russia attacked one or several NATO countries, it would be unlikely to occupy large territory – rather, he believed it would test the red lines set by the West. In essence, this is what Russia has been doing up to now and what the West has responded to with caution – so will Article 5 actually be invoked in case of a direct, open, and armed attack? The intel chief claimed that high-ranking officials in the Russian defense ministry doubt it. This should be an alarming sign to the Alliance – if it doesn’t step up its defense and show resilience now, Russia will keep further weakening the Euro-Atlantic security.

Individual Member States’ Readiness for a Russian Attack

Fear of a possible Russian attack against NATO has spread among other officials, too. In January 2024, Swedish defense chief Michael Byden stated that all Swedes should mentally prepare for conflict. In Britain, the Army chief at the time, Gen. Patrick Sanders, urged British residents to get ready for a level of mobilization not seen since World War II (even though he was criticized for such a bold claim by his boss later). In Germany, officials believed that Moscow could launch missiles against NATO countries. For this reason, NATO called on the allies to link military planning and civil planning. Royal Netherlands Navy Adm. Rob Bauer, who is the chair of NATO’s Military Committee, explained, ‘Financial institutions have a role to play. Industry has a role to play. We need the right infrastructure in our nations to transport military equipment over roads, over bridges. A bridge has to be able to carry a tank.’ On top of this, NATO will also have to resolve the issue of untangling roads and transportation networks in a war in case tons of people move west while tanks and logistics trains move east.

In the context of Russian drones violating NATO airspace, General James Hecker, the commander of the U.S. Air Forces Europe and NATO Allied Air Command, stressed the need for better air and missile defense systems – he believes there will be more such intrusions in the future. Nevertheless, so far, the reaction of member states to the countless airspace violation incidents has drastically contrasted with the above-mentioned calls to ramp up security in the face of the Russian threat.

Not once have victims of these violations openly admitted that the incidents were purposeful. The responsible state behind the April 2022 drone crash in Croatia was hidden. August 2023 incident with Belarusian helicopters flying above Poland also wasn’t enough for Matthew Miller, Spokesperson for the US Department of State, to claim that the alliance was ready to invoke Article 5. Even Latvia, despite openly disclosing that the drone in its air was Russian, officially downplayed the event. The Defense Minister stated it couldn’t be seen as ‘open military escalation’ and reassured that Latvia wasn’t the intended target of the drone.

Romania, in turn, may have been more decisive – it has reported the incidents as violations of international law. In October 2024, it rushed to raise two F-16 fighter jets and two Spanish F-18s used for air policing missions. Rutte called on Romania to ‘quickly and effectively respond’ to violations of its airspace, stressing that air defense remains a priority for the Alliance. On one occasion, the Shahed drone above Romania was even chased by NATO fighter jets.

At first, the Romanian authorities mentioned that they could not directly shoot down the drones as it was prohibited by Romanian law. The promise for change arrived in December 2024, when Bucharest approved two draft laws establishing protocols for handling and shooting down foreign objects entering its airspace during peacetime. However, they still need to be voted on by Parliament and enacted by the president to come into force.

Lately, Poland has shown more assertiveness towards Russia, too. Even if Miller ruled out the possibility of invoking Article 5 after the Belarusian helicopters incident, Polish Minister of National Defence, Mariusz Błaszczak, requested an escalation in troop presence at the border, along with the deployment of extra forces and equipment, such as attack helicopters. In October 2024, the Polish General made a very bold statement by saying that if Russian troops invade Lithuania, allies will, within the ‘first minute,’ strike all of Russia’s strategic assets located within a 300-kilometer range. He declared that they would ‘strike directly at St. Petersburg.’

Conclusion

It appears that NATO, despite stating it would continue to respond to Russian threats in the 2022 Strategic Concept, has not even started doing so. Nearly all incidents with airspace violations have been officially declared accidents—perhaps under the illusion that this would help avoid escalations. Yet, by actively denying that Article 5 is relevant, NATO misses the main point.

Whether or not Russian drones enter the Allies’ airspace on purpose must not be their main concern – people’s lives should. The Croatia and Poland case clearly demonstrated how easily war can cross borders and bring casualties to those not formally participating in it. The fact that Russian drones keep flying above NATO officials’ heads even after they reassure everyone that Poland, Latvia, or any other state wasn’t a target proves that Moscow cannot be stopped by appeasement. Today, ‘sabotage’ and ‘hybrid’ activities may only target specific facilities – tomorrow, they may bring deaths among the local population. It is unclear how their residents will stay safe if the present inaction continues.

Considering the smart strategy of conducting these operations covertly, if Russia launches an armed attack against NATO, it will be just as subtle. In that case, considering the rhetoric of the high-ranking officials up to now, it is highly unlikely that NATO as an alliance will invoke Article 5. After Trump completes his inauguration as the president of the United States in January, the chances will decrease even more. So far, the Republicans have been far more ambivalent in that regard, unlike Biden. Taking into account that the United States is undeniably a leader in the Alliance, such unclear rhetoric and reluctance to actively participate in the defense of Europe suggest the prospect of invoking Article 5 will be even farther than before.

In contrast, the individual reactions suggest that states neighboring Ukraine might respond to the armed attacks by themselves should they target their territory. Poland, in particular, spends around 4% of its GDP on defense, while Romania is currently taking steps towards being able to shoot down Russian drones. Nevertheless, the question remains: how far will they be ready to go? Will they defend from Russian attacks strictly on their territories, or will they strike back at Russia, as the Polish General declared? Considering how slowly the U.S. was approving the permit for Ukraine to strike targets on Russian soil, obtaining a permit to strike ‘directly at St. Petersburg’ with NATO weapons might be even more complicated.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations the authors may be associated with.