516 KB

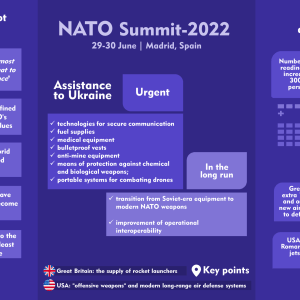

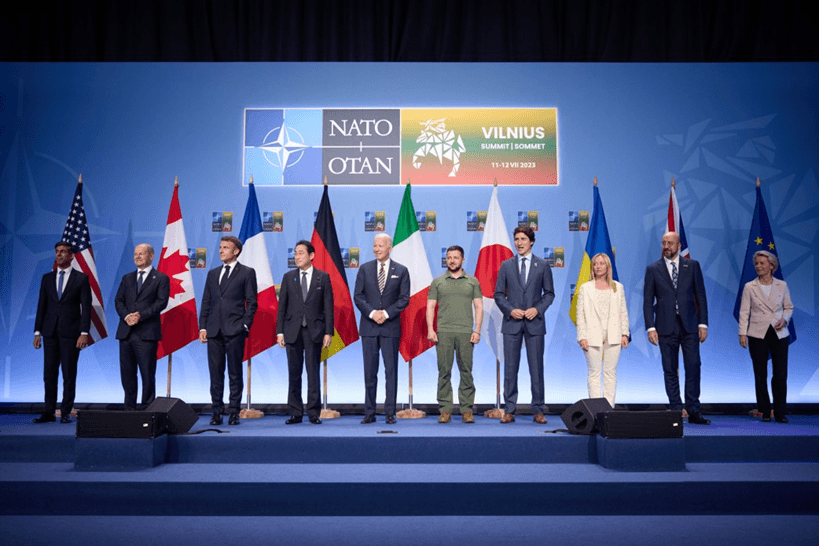

Leading up to the most recent NATO Summit in Vilnius, the informational hailstorm has been covering not only Ukrainian but global media. They were constantly coming back to one question – will Ukraine be accepted or invited to NATO this time? This dilemma was evident after the Ukrainian Presidential Office decided to file an official application to NATO in 2022, at the brink of Russian aggression. Up till a few hours before the start of the Summit’s official part, President Zelenskyi was neither confirming nor denying his arrival in the Lithuanian capital, at the same time demanding an invitation for membership. However, despite bringing some good practical results, such as new weapon supplies and a G7 Declaration that featured the long-awaited security guarantees for Ukraine, a highly anticipated event did not clear out many issues but instead sparked numerous controversies regarding the Ukrainian diplomatic strategy, contemporary media landscape, military power, and future of the NATO itself. Discover how did the Vilnius Summit become a reflection of the bumpy road that Ukraine is going through in its aspiration to become a full NATO member, which hints did it give to make this road a bit easier, and how it gave the long-sought answers for other important questions.

A train “Ukraine-NATO” that has not stopped yet

It is not that easy to transform from a country that is a part of the core competitor of NATO (that picked such a role for itself) to a country that embraces something that was considered to be your enemy. Opponents of this statement argue that the example of Poland, Hungary, Czechia, Slovakia, and even Albania contradict it as these states were in a similar situation. While there may be some truth to this, it’s also not completely accurate.

Natalia Vitrenko. “A woman who will save

Ukraine. Against poverty, lawlessness, lack

of spirituality, unemployment, Nazism, paid

medicine, crime, land sales, US colony.”

During the Soviet times, NATO was a trigger word for Ukrainians. It is difficult to reinvent itself and dust off everyday repetitions of how bad the West is, with NATO being regarded as the full embodiment of the West, and how every single Western person wants to destroy everybody in the Soviet Union. This process of metamorphosis, together with other important sociopolitical processes, such as the transformation of education and the media landscape, takes a long time, but it can bring good long-term results. It could happen gradually, but there were some events that sped this up… sparked by Russia.

Paradoxically, Russia’s vigorous reaction to NATO expansion to the East and paranoid fear of the military bloc on its borders followed by the attempts to “protect Ukraine” from it became the ones responsible for Ukraine becoming closer to the West than ever before. Two revolutions in 2004 and 2014 respectively, which both have a Russian root cause, created a wave of (sometimes too) high hopes among Ukrainians. They realized their need and readiness for NATO (even if not all of them and everywhere in the country) sooner than some NATO Member States’ leaders. Yet, at the same time, up till 2014, Russia was spreading the narrative about NATO taking over the residential blocks in Ukrainian cities and their gardens at summer houses. And despite always admiring the West and listening to the stories of those Ukrainians who have already been there, the fear of the unknown was helping this narrative.

The 2004 Orange Revolution and Ukrainian NATO integration are closely intertwined. In fact, it has been one of the key elements of Ukraine’s former President Viktor Yushchenko’s election campaign and one of those that met the most resistance. The hard security topics were always challenging for Ukrainians, as it is pretty difficult to think about military power and weapons when there is no economic or political stability in your homeland. Leading up to the already infamous 2008 Bucharest NATO Summit, Ukrainians were not entirely mentally ready to join NATO. Comparing the level of awareness about NATO among Ukrainians in 2008 and 2014 and especially now, you can see the evolution, where the starting point was barely knowing anything about the organization, its goals, and what it takes to actually be a Member State. At the same time, high hopes from the Orange Revolution were shattered by the harsh reality of a Ukrainian political interplay between different political groups in pursuit of influence. All of that gave Ukraine a little bit of a wobbling footing for the Summit, where Russia managed to convince the U.S. and Bush Jr. that both Ukraine and Georgia in NATO equal a very risky decision.

In 2010, Viktor Yanukovych, a freshly elected at that time President of Ukraine who was financially and politically backed by the Kremlin, decided to change the destination, trying to embrace neutrality. A neutral status for Ukraine was one of his central campaign promises. In support of it, Yanukovych and his peers were capitalizing on the “NATO horror”. As he tried to say this, it would be better to focus on the economy rather than think about the military. Was it real neutrality, like, for example, in Austria? It is debatable. As the standards for many aspects of the military are the core element of NATO integration, it is definitely fair to say that the Ukrainian military at that time was drifting away from NATO. The arms reduction, the decline in conditions for soldiers, rising corruption, bullying campaigns for “freshmen” of the military draft, issues with gender parity – all of these problems were at their worst during the Yanukovych presidency, and some of them are still lingering as the obstacles on the Ukrainian path to NATO. When Yanukovych’s policies became unbearably Russian, Ukrainians took another leap of faith in a better future with the 2014 Revolution of Dignity.

In 2014, these new hopes helped Petro Poroshenko to get his presidency. He came to power promising to get Ukraine into the EU and NATO topping it all with “finishing the war in two weeks”. When he gained some success in keeping Ukraine on the radar of Western leaders and had some small wins in the course of European integration, all other issues (that were either impossible to tackle for him alone, like Russian aggression) or implementation of reforms (such as modernization of the military complex) were ignored. Indeed, the transformation was happening, but not everywhere, not every time, and not fast enough. All of that, together with other factors such as imperfections in public diplomacy and its efficiency, “lack of fully self-reliant and resilient democratic institutions”, and the worst of them – too big of a focus on creating his own political cult that still damages Ukrainian politics in its most crucial chapter. The very same reasons were making the West skeptical of Ukraine in NATO.

At the beginning of that part, some Warsaw Pact countries were mentioned for a good reason. At times Ukrainian experts present an argument that Ukraine itself is not worse and even, in some terms, better than those countries that are already accepted into NATO. They might hint at the possible prejudice against Ukraine. While this scenario might be one of the possible reasons, we should also keep in mind that the Western lens at this is quite different, and it is similar to the lens they use for Ukrainian integration into the EU. Yes, despite Russia trying to prove otherwise, Ukraine is better at fighting corruption than commonly perceived. Moreover, its progress is not worse than the one in Romania, Bulgaria, and Albania, which are already NATO members. With the current geopolitical trends, certain experts might even perceive Ukraine as NATO Member to be more logical and viable than Hungary.

However, the failed homework of these countries is the reason why NATO is skeptical about Ukraine. As we can see, the rise of far-right politics in Poland and Hungary and the economic instability of Bulgaria and Romania have already created cracks in European security. Yes, the accession of Albania was a risky choice, but it is easier to manage issues in a country as big as Albania than in Ukraine. It is time to understand that Ukraine in NATO is an opportunity for both NATO and Ukraine to become more resilient if the cards are played right. But unfortunately, the West does not present this transparently enough, and all these insecurities tainted the recent Vilnius Summit.

What on earth was in Vilnius?

Even after days passed since that Summit, we still have so many questions. Usually, these summits fly under the radar of the general public, but this time because of the tension over “the Ukrainian case” it looked like a reality show. We had it all – a dramatic commentary, a plot twist, and an ending that leaves everyone arguing whether it was actually a good one.

It was one of the rare occasions where President Zelenskyi could meet all leaders who were interested in helping Ukraine in one place. Stakes were high, and risks were not lower, so it is not surprising that Ukraine chose a risky gambling strategy. It is actually quite traditional for modern diplomacy – try to land on the Moon, so if you fail, you can reach the stars. It seems that this time the Ukrainian team had it in mind – it is acceptable to demand a sharp guarantee that we would be accepted into NATO. After all, the trauma of the Budapest Memorandum still haunts Ukrainians, as it symbolizes diplomatic inefficiency and broken trust for them. To avoid that, Zelenskyi’s team wanted to get something concrete. But again, the lack of willingness to go into the nuance played wrong this time too.

In such challenging times, we tend to understand the complicated processes happening around us through generalization. It is comforting from a psychological point of view. In such a chase, not everything can be generalized and this situation is a perfect example of that.

The idea of giving Ukraine “the golden ticket to NATO” is generally good and has good intentions at its core. However, it is not planned precisely enough. This idea lacks vision, and its justification lacks some more profound understanding. Yes, the Budapest Memorandum is one of the proofs that not every promise is kept in the Western world. But there is one crucial detail – it is not a legally binding document. And there are situations in modern geopolitics when even a legally binding document can be thrown into a trash can. It is indeed painful to give away your nuclear weapons, but would it be more painful to be isolated from the outer world with them?

And what is actually “an invitation” for Ukraine to join NATO? Was there ever any “invitation” of that kind to anyone? What does it mean? Numerous Western leaders repeatedly said that Ukraine would join NATO as soon as the war was over. Simultaneously, people in Ukraine are pumped up for that NATO breakthrough which is needed for…but what is it needed for? Can this “invitation” be a legally binding document? There is really a doubt about it. We might rather have another Budapest Memorandum moment.

It is complicated to calibrate a good strategy for such an event when you have to balance out your messaging for the domestic and foreign audiences, especially when everything is so hyped up for it at home. If Zelenskyi went too soft in Vilnius, he would be criticized for giving up efforts on a battlefield. If Zelenskyi went too harsh, he would risk losing all additional support from the Western partners. If he did not come to the summit at all, he would be ridiculed for ignoring the opportunity and focusing on his demands only. As we can see, the situation itself was definitely a landmine field. The strategy that has been chosen actually worked better at home than abroad, even though initially, it has been tailored to match the American mindset.

The war is a very emotional process, especially when it has been going on for more than nine years. And sometimes, it is hard to process all these emotions in a way that is not damaging to your other activities. Sometimes, politicians are people, too, especially those without a robust political background. At the same time, everything that is charged by intense emotions (no matter if they are positive or negative) is draining energy with time. It is an essential insight for diplomacy, too – the war is emotionally draining for everyone. Especially when it is constantly in the media. For Ukraine, it seems good to always be on display, however, when there is nothing to balance that out, even the smallest misstep can turn into a huge drama. Emotions were the biggest issue with the Vilnius summit. From the psychological perspective, President Zelenskyi charged the situation with emotions when other actors, in that case, wanted to tackle it with a cold head. Imagine a scenario where a child is trying to solve a math problem, and a teacher starts screaming at them, demanding to solve it immediately. Because if they do not, the teacher might not get paid and will have nothing to pay their bills with. This accurately reflects the situation, and it naturally backfired. Sometimes emotions are a very useful and powerful tool, but not when everybody else is trying to calm down in an already very emotional situation.

Still, everything is not as bad as it seems. That summit gave Ukraine the security guarantees that fixate steps that Western partners will do if Russia escalates in the future. It gave more weapons, which is important in the context of the counter-offensive. After all, Ukraine received a guarantee to be accessed to NATO without a Plan of Action for Membership, similarly to Finland. Despite all of that, Minister of Foreign Affairs Dmytro Kuleba stated that the Ukrainian road to NATO became “shorter, but not faster”. But does not it mean that with fewer obstacles it would be easier for it to actually get there? As we can see, this fever dream of a Summit detected some misunderstandings in the Ukrainian approach not only to the Atlantic but also to European integration. How not to get this process further lost in translation?

The current NATO scoreboard

It is a challenging task not to lose sight in the case of the current diffusion between the NATO member states. In fact, they are divided on how to support Ukraine and whether to invite it to join the Alliance. Many of Ukraine’s Western partners, except for a few, have different best-case scenarios in mind for Ukraine, and these are not always NATO membership. In addition to Hungary’s well-known position against Ukraine’s accession to NATO, the United States also has a fairly clear stance on this issue, saying that it is inappropriate for Ukraine to join NATO right now. At the same time, under the influence of the full-scale invasion, countries such as France, Italy, and Germany have become more positive about the idea of Ukraine joining the North Atlantic Alliance than before. However, it is difficult to speak about clear blocks of positions within NATO, except for Poland and the Baltic States, which are unanimously in favor of Ukraine’s accession.

As we can see, the positions and opinions of countries change under the pressure of circumstances and recent developments on the battlefield. Even saying that Germany is more positive than before does not mean the same confident support in statements and actions as the above-mentioned countries. It should be taken into account that Chancellor Scholz is acting very carefully on this issue, and the German Defense Minister stated that Ukraine can count on joining the Alliance and the influx of investments only after the end of the war. So, there is unequivocal support for accession from a group of countries, including Poland and the Baltic states, while other countries are careful in their statements on this issue.

However, it is worth noting that the Allies never agreed on clear goals of the war, nor on how Ukraine should win. Unfortunately, there is also an error on Ukraine’s part. Since January of this year, the Ukrainian counteroffensive has been one of the main topics of discussion. After the transfer of German Leopard 2 tanks to Ukraine, the Ukrainian media space was filled with statements that tanks and infantry fighting vehicles such as Marder, etc. were needed to prepare for a counteroffensive and breakthrough of Russian defenses in the temporarily occupied Ukrainian territories.

In May, Ukrainians and partners were still expecting a counteroffensive, which remained a hot topic in the media. This strategy coexists well with the task of obtaining weapons, but it also created somewhat unrealistic expectations among Western partners. Despite the fact that Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba emphasized that the upcoming operation should not be perceived as a “decisive battle” and shared the opinion that Ukraine may need more than one counteroffensive to liberate all the temporarily occupied territories, this did not help to reduce expectations. For example, in an interview with The Guardian, the Czech president said that a counteroffensive could be the “last chance” this year because it would be difficult for Ukraine to quickly train new troops if the Armed Forces suffer heavy losses if they are not well-prepared for offensive operations, and it would be extremely difficult to re-provision the necessary ammunition and fuel.

At the same time, the Vilnius Summit also confirmed that the strategy of “last chance weapons” is not that efficient in its informational planning. After all, those who communicated those needs from the Ukrainian side were portraying various types of weaponry in a progressive timeline as its last chance, which is technically true, but in terms of diplomacy is not clear enough. Therefore, Europeans became tired of the “last chance” narrative and started to pay less attention to the decisive matter of military help for Ukraine.

Observing the informational approach of the President’s Office to NATO, it is evident that such an approach was targeted solely toward the United States. Unfortunately, it backfires as many representatives of the European and Ukrainian political elites consider this to be a confirmation of the narrative of Russian propaganda about the U.S. being the only real leader in such formats and Europe being only its puppet. How can something that is created only for the American target audience work out in Europe too, if there are a few subregions with different media contexts and cultures? For example, while video appeals of Zelenskyi at Snake Island worked out well for the American audience, Europeans did not get the message very well. It is good to balance out possible risks and implications of the media product the President’s team shares with an international audience. It is even more important to create something that would be palatable for both domestic and international audiences.

Still, the summit in Vilnius did not bring Ukraine an official invitation to join NATO and left open all further scenarios for the development of cooperation with the Alliance. However, it is worth noting that this does not slow down the process of Euro-Atlantic integration for Ukraine, but it also does not speed it up. Although the political objectives set by Kyiv did not work, the task of “getting weapons” worked again at the summit. As early as August, the 11-nation coalition may begin training Ukrainian pilots on F-16 fighter jets. All of that leaves a lingering feeling of chaos and confusion, where answers are needed fast to move on.

How should Ukraine proceed further?

There are many ways to improve the current situation. For instance, as previously mentioned the damage was done by an emotional approach to communications. One more example of this is the debacle between the UK’s Minister of Defense Ben Wallace and Zelenskyi. It appears that actually, the media focused on the emotional part which appeals to the public more, though Wallace’s core message was about the difficulties of getting weapons to Ukraine. Yet the Ukrainian President’s response appeared too emotionally charged. There might have been alternative, perhaps more diplomatic, ways to communicate his message. After all, in his role as the President of a parliamentary-presidential republic, not all matters fall within his direct purview, including the conduct of individuals communicating with Wallace. It would look even better from the perspective of Ukrainian integration into the EU, as it would show the power to delegate in such difficult times.

There seems to be a discrepancy in perceptions when it comes to the provisioning of critically needed weapons to Ukraine. While Kyiv may view the requested aid as a relatively small portion of foreign nations’ capabilities, the reality in these donor countries, particularly those in the West, might be different. For instance, changes in the U.S. military manufacturing sector, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, illustrate the complex interplay between large defense conglomerates and smaller contractors. This complexity, alongside resource and facility constraints, could impact the speed and scale of weapon production and distribution. All of these details have to be taken into consideration while asking the West for more weapons.

But after all of that, a question remains – why does Ukraine need NATO? To answer simply, many in Ukraine see NATO membership as a magic wand able to solve all problems. It is just a vehicle for its aspirations, reforms, and security improvements, like a train that goes to its final destination. While Ukrainians might think that they are ready and deserve membership, it would be good not to put heads too high yet, as there are still some issues in the Ukrainian military complex. We have to reject a mindset where security is only about the military and the military is only about weapons and the number of people. Ukraine needs NATO to improve the situation with the rights of soldiers, the procedures of a military draft, the bureaucracy at the local military centers, the living conditions of the military, their equipment, their knowledge and training, and the situation with the women and LGBTQI+ rights in the army. There is still so much to learn, and NATO can be that helping hand that can push Ukraine toward these improvements. However, the utilization of such aid ultimately rests with the Ukrainian government. It would thus be strategic to remind international counterparts of Ukraine’s need for NATO to progress with the proposed reforms, and of Ukraine’s readiness to swiftly implement these reforms. Negotiations could potentially be smoothed if the dialogue was to incorporate discussions on potential successful outcomes that could arise concurrently with the provision of aid. After all, Ukraine has no desire to let the efforts made and sacrifices endured be in vain.

by Artur Koldomasov, Anastasiia Hatsenko

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors, and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations the authors may be associated with.