629 KB

Death of the Russian Opposition

People closely involved in the XXI-century political research may tell you that an efficient opposition in any country cannot exist without the independent or at least diverse media market on that particular territory. At first glance, it seems modern Russia barely qualifies for that criterion. Many Western opinion-makers say that even though the Russian media market is tightly grasped in the Kremlin’s hands, encompassing everything from political agenda to entertainment, there are still “major” media outlets there with “high-quality” reporting that are oppressed by the Russian government itself with its regularly updated “foreign agent”[1] mechanism. But, as we can see, even despite the enormous political support from the West for the oppositional movements and figures, the most famous oppositional figures in Russia could not make waves and change the current political conjuncture. Furthermore, in the constant pursuit of “the Russian democratic transformation,” the West itself is blind to see that, in case of ascending to power in Moscow, there are no guarantees that the “opposition” will play by the Western rules. Among the endless mantras about the struggle of the Russian opposition, these opinion-makers just forget to see the evidence on the surface. Unfortunately, the diagnosis for the Russian opposition is death. Violent, cruel, and long. And not as recent as you might think.

The Russian opposition did not die in one second, but its death was unseen when it happened, just like the Russian tradition says. The exact day of death is October 7th, 2006, when one of the most prominent figures in Russian journalism, Anna Politkovskaya, was murdered. There are only a few journalists (all of them women, by the way) who came close to the courage and impact of Politkovskaya with her high-quality reporting of both the Chechen wars and the cruelty of the Russian regime in that context. She openly criticized Putin and Kadyrov for their method of targeting civilians during the armed conflict (which became the signature style of the Russian army). But her death did not occur as a result of her murder. It happened when Russia stopped caring about it, and it happened almost immediately.

The extensive and even drowning degree of conformism and carelessness became one of the most defining features of the Russian psyche as we know it. Before her death, Politkovskaya’s materials were highly controversial, and the country was basically tearing itself apart based on whether they do believe her reporting or not. It was a heavy-weighted dilemma for many Russians – to think of a woman describing the atrocities of something your brother or father is doing many kilometers away from you or to be loyal to your country and your governor (or Czar in that case). The intensity and importance of the concept of loyalty for the Russians have their religious roots, as loyalty is one of the core principles of the Christian Russian Orthodox faith concept. And it played Russia the fool in the case of their democratization — only a few people paid attention to the Politkovskaya murder and treated it as seriously as it should have been. It was the watershed moment when the parasite of carelessness infected the whole Russian mentality and became its main feature. People in rural Russia did not care because their lives were already poor and they had to think in advance to survive (and the situation did not change that much). People in megapolis Russia did not care because they did not lose their comfort with that pile of events. Why study if you can pay for your grades? Why care if nothing changes? Why do something if that is not my job? – it became the core mantra of Russian existence.

This is one of the arguments that support the claim that is rarely heard in Europe but loudly voiced by the Russians themselves: mentally, Russia became a part of Chechnya. The media situation is one of the indicators of this in terms of regional censorship and the historical memory of the region as a whole. Chechnya was pioneering among the Federation’s regions in local journalism’s oppression and fear-mongering of those who criticized the local government. When the Kremlin did not withdraw its financial support of the region because of this but build-up its financial support enormously, other regions understood that the key to receiving more money is to oppress to impress the Kremlin, not to liberate.

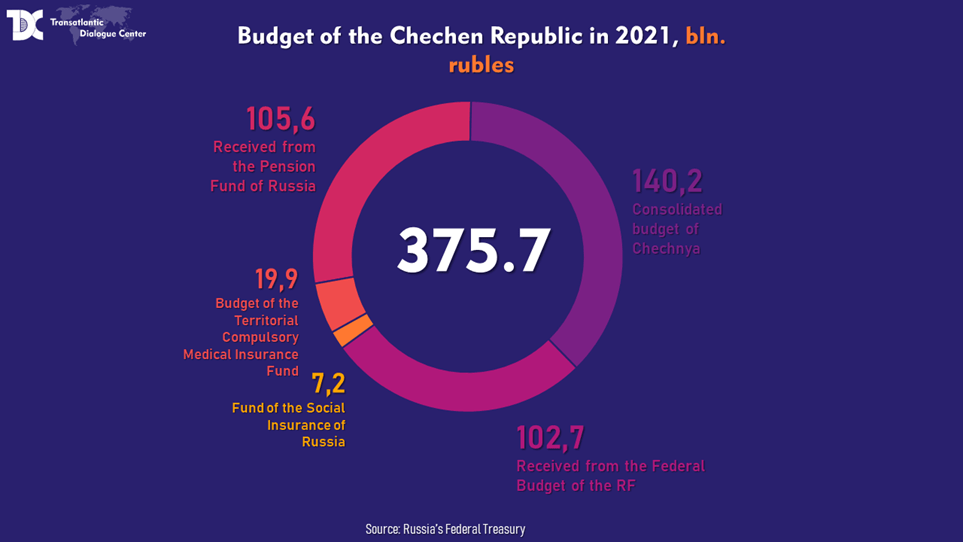

From 2001 to 2016, the Chechen Republic received over 669.3 billion rubles from the federal budget in the form of subsidies, subventions, and grants. For several years now, the republic has been one of the most subsidized (in 2016, only the Republic of Ingushetia received more from the federal budget). But even these numbers may turn out to be understated, as recently head of the Republic Ramzan Kadyrov revealed that in 2021 Chechnya received 10 times more than stated by official data – 375,7 billion rubles compared to the 33,5 billion claimed. Russian economist Sergei Aleksashenko claims in his comment to the ZNAK media outlet that Kadyrov’s statement may be true.

“This amount, it seems to me, was guarded by the Russian budget – by the Ministry of Finance, the Kremlin – as a military secret, in much the same way as spending on the Ministry of Defense, as classified articles. Because, in addition to the subsidies that exist in the Russian federal budget for the Chechen Republic, there are also various other programs that are being implemented on the territory of this republic,” – he said.

Of course, not everybody in Russia is obsessed with ideals like these. Still, ten thousand against 140 million is not a very equal and efficient proportion. Furthermore, the Politkovskaya murder signaled two essential lessons for the Russians – impartial reporting is a threat, and staying alive is the top priority. The Kremlin even extensively monopolized the culture of entertainment on television – the producing and broadcasting TV channels, which are partially or entirely owned by the state, are focused solely on entertaining series, stand-up shows, and sketches (for example, TNT).

There are processes that have definitely prognosticated the death of journalism in Russia – the violent takeover of the NTV, TV6, and TNT TV channels. However, the Politkovskaya murder and later the death of her colleague Nestemirova became the nail in the coffin of Russian journalism at its essence. Yes, it tried to recover with numerous media projects, but all of them became hysterically afraid to take risks and have at least a pint of courage that their late colleagues had.

Afraid to Exist: Modern “Oppositional” Russian Media

Many Europeans love to use such media outlets as Meduza and TV Rain as an excuse for the Russian opposition and support them by different means. The situation with Latvian authorities revoking the license of TV Rain for numerous violations in their broadcast started the empty and useless outcry of not only the European fans of the thought that Russia is European but also the Russian “oppositional” leaders themselves. The crying video of TV Rain’s CEO was the peak of the absurdity of the media noise around the story because the Latvian authorities acted according to the law, and the channel was given a broadcast license in the Netherlands. It was that absurd that instead of some accountability, the mentioned parties involved tried to make people forget that Latvia has always been the country with one of the strictest media laws in the EU. With that in mind, the whole point of TV Rain’s “Latvian crusade” does not make any sense.

If you look closer at the content of both of these outlets, you may find numerous violations of the concept of impartial and independent journalism. For example, in many materials, both Meduza and TV Rain shift the focus toward the Russian vision of the conflict, ignoring the whole range of social and political pretexts. Furthermore, while portraying themselves as impartial sources of information, they tend to present information from a subjective point of view with an intense pattern of victimization of Russia, which is very similar to the Kremlin’s official narrative abroad. Because of that, there is even a conspiracy that the mechanism of “foreign agents” has been created and promoted by the Kremlin to gather more support and notoriety for the “oppositional” media outlets in Europe and the United States.

Yes, there are reliable independent Russian media outlets, such as Current Time, Mediazona, and Novaya Gazeta Evropa. But their reach is not enough to substantially impact the circumstances of Russian reality. At least, it is not available everywhere in Russia in the infrastructural context. Taking into account how big the country is, the idea of a “leading minority” may not work out in Russia. To get real and efficient change, these media outlets must be available to most age groups and regions. Unfortunately, it seems too unrealistic at the moment. But people may ask, “Why do you say so?”

Russian Infrastructure as the Obstacle to the “Opposition”

We may wonder – why things did not work out with the Russian democracy. The answer may be surprising for you – it comes to the Russian infrastructure. Many Europeans forget that Russia is enormously unequal in terms of its development. The gap is so vast that Russia itself could be easily divided into three separate states – the Republic of Moscow & Saint-Petersburg, Chechnya, and Middle Russia. While in Chechnya (specifically its capital, Grozny), the Kremlin rains and pours to tame the region and keep it attached, Moscow and Saint-Petersburg are developed and prosperous because the country’s business is primarily focused in these two cities, and the government is heavily promoting this instead of diversification of the economy. Middle Russia feels like a separate planet compared to these cities – many Russian towns and villages do not have access to gas, tap water, or heating. There is even a large percentage of Russian places where the schools do not even have a properly working public bathroom, let alone private bathrooms with toilets at home.

The Russian “opposition” did not work out because it got drowned in its condescendence and snobbism. Unfortunately, that is a massive trap for the European “intelligentsia” too – they must understand that not everything is decided in huge cities. Protests in Russia will be effective if the entire country, from Krasnodar to Vladivostok, rises up against the regime. But unfortunately, people chasing survival there, especially those with the flare of the Soviet mentality, may care about their own issues more than some guy in Moscow who wants to overthrow the government. And yes, your sandcastles are being completely shattered now – the Russian youth also does not care. Russian pop culture does not care. We are talking about a country with vast natural resources and human potential. But according to the 2020 Levada-Centre survey, only 19% of young Russians care about politics, which is especially interesting when many aspects of life in modern Russia are intoxicated with its political conundrum.

There is one important lesson in all of this to learn – actions create an impact. Instead of trying to somehow prove to middle Russia that it is worth walking the same road with him, Navalny has always been stuck in the vacuum of showing the ugliness of the regime. The situation could be much different if he or other Russian “oppositional” leaders would do some critical infrastructural projects in middle Russia, so people could see the work done themselves. This idea has been supported by the fact that many Russian local governors are using the same technique as a part of their election campaign. Yes, the Russian elections are a theater play where everybody has their roles, and yes, it is absurd to actually work only for the elections and during the campaign, but that is how it works when your village does not have a normal road, and there is a guy who has finally made it.

Instead of working on such projects (including the educational track) in rural Russia, the Russian opposition was talking to itself and its supporters mostly in huge cities. Now, when they need that notoriety to overthrow Putin, they cannot get it because people here either do not recognize these faces or do not want to. It is challenging for a person with knowledge of what modern Russia is to imagine how people in (let us call it) Kemerovo vote for Navalny or Shulman. Some of them may know them but will not vote for them because they are distant (also take into account the culture of hatred against elitism in middle Russia). But it may not even be surprising that some people there do not know these last names.

The necessary fields to work on eventually got lost in the rumble that the Russian “opposition” is constantly going through in pursuit of power. The phenomenon is that funny that one of the candidates who actually tried to play with middle Russia in its election campaign and had a better name recognition there than other oppositional candidates was actually a Russian “Paris Hilton,” Kseniya Sobchak, who has close ties with the Kremlin itself. Another “oppositional” figure that sparks interest in that context is stand-up comedian Maksim Galkin, who is widely popular in rural Russia. However, he barely touches politics in terms of activism and real projects, so it is complicated to imagine him having a significant impact in such circumstances. Still, in a quest for “Russia’s savior,” Europe is looking at Russia with rose-colored glasses, ignoring a middle Russia as a whole. The fact that addressing middle Russia and the usage of an infrastructural approach is working is confirmed by the fact that Russian towns at the border with the EU countries are more skeptical towards the Russian intentions in the war against Ukraine. For instance, Current Time’s documentary series The Dangerous Neighbourhood tells the story of Russian towns on the border with Norway, where both countries developed the Barentsov-Region project. With this in action, Russians from these towns could go to Norway without visas. However, the project has been suspended by Norway because of Russian aggression against Ukraine. Locals express their despair about the Kremlin’s actions in Ukraine, but in comparison with the whole country, it is still not enough.

Conclusions

It is difficult to understand Russia and what can change it sitting in a neat and comfortable German town or Brussels. Many European leaders are throwing a lot of money at people and initiatives that have no impact at all, hoping for a change and expressing their disappointment when it does not happen as planned. Unfortunately, they have to understand – there is no efficient Russian “opposition” at the moment. It cannot exist with the heavily restricted media market, lack of contact with most of the country, and constant conflict inside. Instead of chasing the pursuit of a “perfect democratic Russia,” it is better to work on the “ground zero” level and not hope that everything will change overnight, but to recognize that the process may be complex, surprising, and demanding along the way.

[1] The foreign agent mechanism is a Russian legislation adopted in 2012 that requires noncommercial organizations that receive foreign assistance and that the government deems to be engaged in political activity to be registered, to identify themselves as “foreign agents,” and to submit to audits. It imposes economical and practical punishment on Russian media outlets, which are registered as foreign agents, and share their content publicly without the authorized disclaimer, as well as against personalities, and people who share the content of such media without a disclaimer. The criteria for the selection of those outlets and personalities are vague. The list of media outlets and personalities targeted is created and regularly updated by the Kremlin and includes those who have criticized the Russian government in different ways, including indirect ones.