Since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Russian soldiers have started deporting residents of the temporarily occupied territories to the Russian Federation.

The Russian military said that since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the total number of “evacuated” Ukrainians is 1,936,911, including 307,000 children. However, it is difficult to name the exact number of deported residents of Ukraine due to the non-transparency of the process, as well as the fact of deliberate inflation of the data.

According to the official information of the Ukrainian government, as of mid-June, 1,2 million to 1,5 million Ukrainians were deported, including about 300,000 children. They are often taken to remote regions of the Russian Federation and issued documents prohibiting them from leaving for two years.

Russia itself calls its actions “evacuation without Ukraine’s participation.” This statement itself confirms the illegality of the actions of the aggressor state and the violation of international humanitarian law.

Forced resettlement of civilians from the occupied territory to the territory of the occupying state is a violation of Article 49 of the 1949 Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War and Article 85 of Additional Protocol 1 to the Geneva Conventions.

Extraction of civilians to the territory of the aggressor country is possible only if their home state does not agree to accept the civilian population (which does not happen in this case, because Ukraine seeks to return its citizens to the territories under its control). The Russian Federation should stop shelling for the duration of the green corridors’ existence, promote their work and cooperate with international organizations that protect the civilian population. Instead, the military of the occupying country deports not only physically people but also creates all the conditions under which citizens of Ukraine in the temporarily occupied territories have no other means of evacuation except through Russia.

“Deporting residents of Mariupol, in general, citizens of Ukraine to the territory of Russia during the war, is not an evacuation. There was no full-fledged evacuation from Mariupol to the territory controlled by Ukraine in the direction of Zaporizhzhia, – Russia blocked it. Despite Ukraine’s constant attempts to ensure such a corridor and evacuation. The only exception is the recent evacuation of people from the Azovstal bomb shelters,” says a charity worker Nataliia Yemchenko.

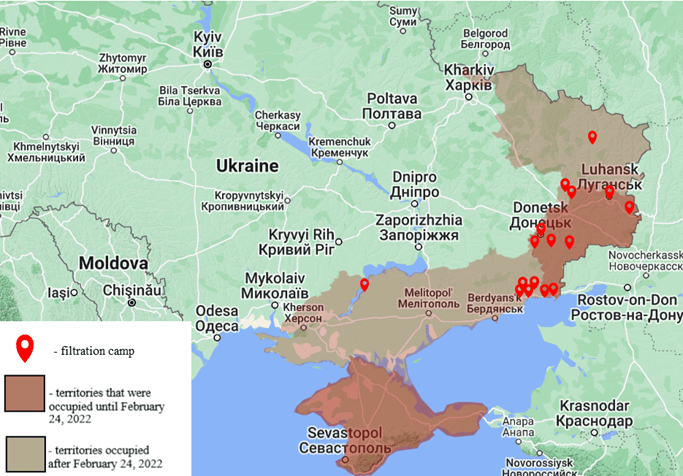

The fact that the “evacuation” is not Russia’s humanitarian mission is supported by the fact that all Ukrainians who were moved out from the war zone pass through the filtration camps created by the Russians on the temporarily occupied territories of Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Ukrainians from the frontline regions occupied after February 24th in particular, Mariupol, Novoazovsk, Manhush, Bezimenne, Donetsk, Luhansk, Kharkiv, Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions are forced to go through the filtration process. After, Ukrainians are forcibly deported to the territory of Russia.

It is reported that the Russians created at least 18 filtration camps, where about a million Ukrainians had to go through “filtration process”. Lots of them may be found near Mariupol, where the filtering measures began at first. There are camps in Manhush, Bezimenne, Kozatske and Nikolske. They are also in the rear of the “DPR” – in Donetsk, Dokuchaievsk, Novoazovsk, Starobeshevo, Amvrosiivka. According to the report of the Defense Intelligence of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine, in the Kherson region, such camp operates in the village of Velyka Lepetykha.

There, people have to live in harsh, unsanitary conditions for several days, during which they are subjected to perquisition, long-hour interrogations, and other examinations, as well as document confiscation. Men are treated especially harshly. They are often separated from the general flow of “refugees” and resettled separately. Men are stripped in search of tattoos that could testify to their belonging to the Azov regiment, hands are examined for calluses from weapons.

Veronika, whose boyfriend got into one of such camps testifies about conditions the following: “There is no opportunity even to wash up. Conditions are completely unsanitary. Absolutely all men have symptoms of SARS, some even have pneumonia. The situation is getting worse every day: three people in Bezymenny camp have an open form of tuberculosis. There are no medicines or doctors. There has already been a fatal case: the man died from the failure to provide medical care! The military stood, watched the man suffocate, and refused to call an ambulance. When the agony was over, they packed the body in a sheet and took it away.”

In the camps the deportees are fingerprinted, photographed in profile and full face, their personal information is put into a special database, phones are connected to computers, merging all the contents (photos, number of subscribers, correspondence in messengers and chats) which are carefully studied. The occupiers are trying to get information about the participants of the Joint Forces Operation and their environment, involvement in the work of the Ukrainian security forces, journalism, and social activism. Often, it is because of any manifestation of civic position that people may not pass the filtration.

Then Ukrainian citizens are taken by bus to the Rostov region in Russia, and from there to places of temporary residence (special camps, dormitories, etc.) in more remote, economically depressed regions. Citizens of Ukraine, taken out of the war zones, were found in 45 regions of the Russian Federation, in the Far East, in the Krasnoyarsk Territory, Chuvashia, Khakassia, Penza, Yaroslavl, Vladimir Regions. There they are forced to obtain Russian passports and get a job through employment centers, after which they are issued a document prohibiting them from leaving Russia for two years.

“This is a real concentration camp only in a modern version. Surveillance cameras are everywhere, they seem to be installed even in the toilet, barbed wire, and machine gunners, who, from time to time, are pulling the shutters. It seemed to me that they were pleased to see how people shied away at these sounds, and they deliberately clicked the shutters to have fun. Rubbish and dirt everywhere. Mom got some kind of infection [there]. She was constantly vomiting,” recalls Tatyana Starykova, who was in the camp in Taganrog.

According to the former Ombudsman for Human Rights in Ukraine Lyudmyla Denisova, Russia has been preparing for the mass deportation of Ukrainians since the beginning of 2022. The Kremlin sent directives to the regions where Ukrainians are now being taken with information on how many camps for deportees are needed and how many people they should accommodate.

The Russian Orthodox Church also participates in the deportation process: it resettles deported people in its churches and monasteries. As the journalists of the Ukrainian edition “Slidstvo.Info” found out, since the beginning of the full-scale Russian invasion, the Ministry of Emergency Situations of the Russian Federation regularly sends reports on the occupied territories and deported Ukrainians to one of the departments of the Russian Orthodox Church. Church members are informed day-by-day about military operations in the occupied territories, as well as about forcibly deported Ukrainian citizens, routes, and times of delivery of people to the Russian Federation. Almost every region where Ukrainians are brought has its own diocese that deals with the issues of displaced people.

Returning to the Motherland may be a difficult task for deported Ukrainians. It depends on whether the occupiers have not taken away the Ukrainian passport or forced the person to sign documents on obtaining refugee status or “asylum from war” during the filtering. If a person was made to choose this status, the passport of a citizen of Ukraine would be taken from them, and a certificate would be issued instead. This ties them to a certain region and a certain job. They will not be able to leave the region officially for at least a year. Theoretically, according to the law, you can refuse the status, and the Russians are obliged to return the passport. But Russia and rule of law are opposite things.

It is possible to return home with a biometric passport. You can leave via Estonia, Georgia, and Latvia, by air to Istanbul, and then fly to European countries. For those who do not have a foreign passport, the way lies through Moscow, where there is a direct bus route across the Latvian border, as well as one leading to Belarus. But the price of tickets, fear of the unknown, and severe exhaustion from stress force many to stay in Russia, especially elderlies, who are left without means of communication, funds, and hope of having a place to return.