2 MB

Key Takeaways

- Europe must urgently build autonomous defense capabilities to make sure it can protect itself and ease the pressure on the US. The EU can no longer be fully dependent on US security guarantees. Russia’s war on Ukraine and Washington’s pivot to Asia and Middle East have made a post-American European security order both more likely and more urgent.

- Ukraine is not a burden but a critical contributor to European defense. With a resilient and rapidly scaling defense sector, especially with regard artillery, ammunition, drones, and joint ventures with European counterparts. Ukraine is becoming an industrial and operational backbone for European security.

- The EU has developed the right strategic documents, but faces real implementation challenges. From the Strategic Compass to the ReArm Europe Plan and SAFE, the EU has frameworks in place, yet it still faces legal, financial, and political hurdles to achieving defense integration at scale.

- Closer EU–Ukraine defense industrial cooperation is a strategic win for the US as well and, therefore, must be supported by American decision-makers. Greater EU self-sufficiency enables Washington to rebalance toward the Indo-Pacific without leaving Europe vulnerable. Supporting this process is a strategic investment for US decision-makers and America’s global interests.

- A new Road Map is needed. A jointly agreed transatlantic Road Map between the EU, US (NATO), Ukraine, and other close partners to clarify burden-sharing arrangements, timeline goals, and defense production responsibilities for the coming decade. If a significant US retreat from Europe is to take place, it should be well-planned, mutually agreed upon, gradual, and organized.

Introduction: Why Europe Must Build Defence Capacity amid US Rebalancing and Russia’s War

The question of building European defence is as old as the process of European integration itself. What began as a peace-oriented project after World War II to guarantee stability on the continent, the European Communities and later the European Union (EU) were designed to institutionalize peace. Initially, the European project focused on intertwining and integrating national economies and key sectors, including coal and steel relevant to military production, in order to make the outbreak of another war less plausible. Security, including the nuclear umbrella, was mostly provided by the United States (US).

During the Cold War, the EU was able to concentrate on developing non-defence common policies, essentially adopting a low-key security posture grounded and instead leveraging its economic and normative power, while largely outsourcing its defense and security to the US and NATO.

Despite recurring proposals to establish a European Defence Union (EDU), that is, to reduce Europe’s dependence on US security guarantees, such initiatives consistently faced pushback from both within Europe and, paradoxically, from Washington itself. US policymakers often cited the risk of duplicating NATO’s functions. This long-standing miscommunication between the US and Europe, combined with a lack of forward-looking strategic planning and trust, led to the consistently shrinking attention to European defence. Following the Cold War, and in the absence of a perceived immediate military threat from Russia, European defence budgets declined, armed forces stagnated, and strategic focus on conventional security steadily diminished.

Today, however, the imperative to build European defence, whether through the EDU, a broader EU strategic autonomy, or a strengthened European pillar within NATO, has become more urgent than ever. Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine has reintroduced a direct military threat to Europe. Not to mention the fact that NATO’s Secretary General Mark Rutte recently stated that Russia could attack a NATO member state within the next five years due to its increasing domestic production of military capabilities, and such a possibility is also confirmed by several European intelligence services, including Germany’s. Simultaneously, the shifting global balance of power has prompted the US to rebalance its security commitments. Washington now faces overstretched resources due to the tensions in the Middle East and the challenge of containing its primary strategic competitor: China.

This analysis outlines the key developments shaping the reconstruction of Europe’s security architecture in the context of potential US disengagement from European defence and its reorientation toward Asia. Some analysts already describe this moment as pivotal, one in which the EU must prepare for a so-called post-American European security order.

Taking into account Russia’s ongoing aggression against Ukraine and the Kremlin’s reluctance to engage in diplomacy meaningfully, even amid US President Donald Trump’s attempts to push for negotiations, this paper explores how Europe, together with Ukraine, can navigate the enduring challenges of war and waning US engagement, in order to achieve a greater degree of autonomy and continue providing sustained support to Kyiv, while stressing the need for Americans to stay in the loop.

Evolving Frameworks for European Defence: From Debate to a Comprehensive Long-Term Strategy?

As mentioned previously, long-standing tensions and misunderstandings between Europe and the US regarding the need for Europe to do more to ensure its own defence have significantly impacted the state of affairs in this domain. These dynamics have, in fact, slowed down the EU’s potential to meaningfully embrace defence integration. On the one hand, the US has long encouraged Europe to ease pressure on American resources by building up its own defence capabilities and meeting NATO’s 2% GDP spending on defence target. On the other hand, Washington has often criticized European governments for encroaching on NATO’s territory whenever concrete initiatives were proposed. This ambivalence contributed to significant budget cuts across European militaries, slowed domestic production, weakened defence infrastructure, and made much of it outdated and unfit for rapid deployment. As a result, the EU lost momentum in developing a stronger defence and security posture between 1992 and the early 2000s. Another issue here is the persistent scepticism among European publics and policymakers about increasing defence spending, even as a major war unfolds at the EU’s doorstep.

In the current transatlantic reality, Washington has set a course to reduce its involvement in European security and intends to significantly limit its military support for Ukraine, most likely to preserve its own defence stockpiles and capabilities for its pivot towards Asia. The American vision is grounded in a willingness to be better prepared for a potential outbreak of conflict in the Indo-Pacific, particularly over Taiwan. Under such circumstances, the NATO 2% of GDP defence spending benchmark no longer seems sufficient to guarantee Europe’s security. A more comprehensive, consistent, well-planned, and well-communicated strategy is urgently needed to enable European governments to succeed in the domain of defence and security.

This is essential for several reasons. First, the EU must find ways to ensure its own security in the face of declining US commitment to Europe. Second, the EU must be ready to fully or significantly sustain Ukraine militarily, especially since diplomatic solutions remain elusive. Third, one of the key lessons from Russia’s war against Ukraine is the danger of overreliance on external suppliers and even most trusted partners. These supply chains may be vulnerable or constrained in wartime. Therefore, the EU must ramp up domestic production, revitalize its defence-industrial base, and ensure that joint procurement, manufacturing, and interoperability mechanisms are fully in place.

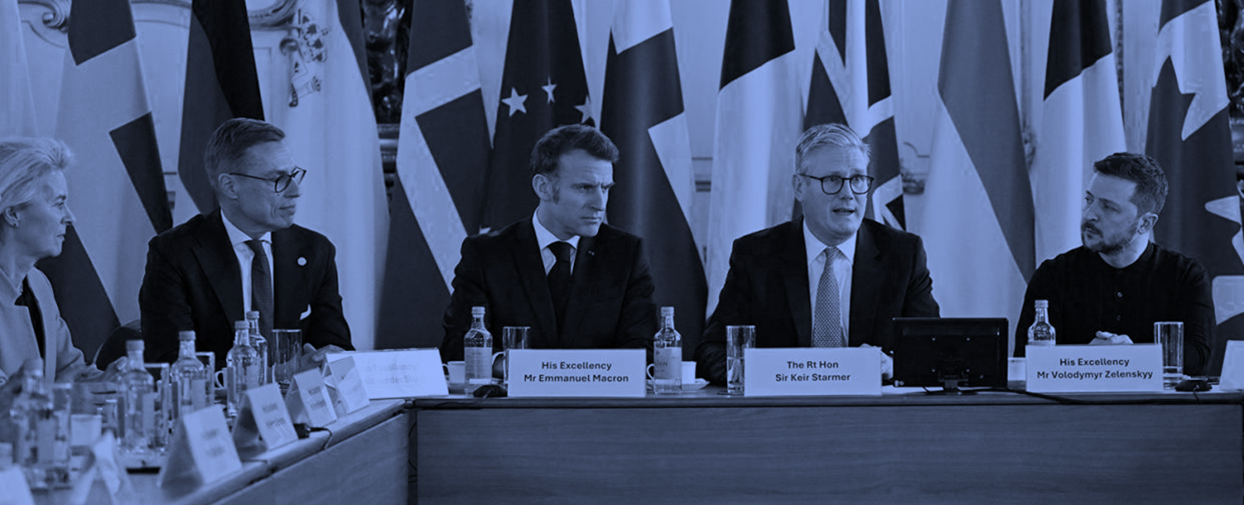

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the EU has undergone a number of meaningful transformations. The tone and emphasis set by the leaders of the EU institutions, such as, for instance, Ursula von der Leyen’s vision for a geopolitical Commission, have stressed the imperative for the EU to act as a global security actor, a defender of peace, freedom, and democracy, and a long-term security partner to Ukraine.

In parallel, broad debate among EU Member States, institutions, and the wider public has led to the adoption of several crucial frameworks and strategies aimed at guiding the Union’s transition toward a more robust defence posture. Nevertheless, the EU’s efforts to build a common European defence still face serious legal, political, and technical challenges. These include, most notably, the tension between the national prerogative over defence matters (enshrined in Article 4.2 of the Treaty on European Union) and the intergovernmental nature of EU defence policy, which requires consensus among all 27 Member States. This process is often too slow and politically constrained, particularly when it comes to decision-making during times of crisis.

Among the most important strategic documents adopted since February 2022 is A Strategic Compass for Security and Defence. This marked the first major step toward positioning the EU as a credible global security provider. It lays out a shared strategic assessment of threats, a common strategic culture, and the steps necessary to strengthen the EU’s defence and security capabilities by 2030.

From Vision to Action: Tools, Priorities, and the Politics of Implementation

To support defence-industrial capacity, the adoption of the European Defence Industrial Strategy (EDIS) organisiert und wird gemeinsam mit der European Defence Industry Programme (EDIP) has been pivotal. These initiatives set long-term goals to promote joint defence procurement, boost intra-EU defence trade, and support the broader vision of “producing and buying European.”

One of the most recent and influential documents is the White Paper for European Defence – Readiness 2030, introduced by the new leadership of the European Commission: High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Kaja Kallas and Commissioner for Defence and Space Andrius Kubilius. This White Paper incentivizes capability development in response to both short- and long-term threats. It also reflects the reality of Russia’s continued aggression and the potential risk of its military success amid waning US engagement. It calls for stronger collaboration among EU Member States, greater joint procurement, and deeper cooperation with European defence industries through aggregated demand and long-term contracts.

The document also underlines the importance of international partnerships and, in particular, close coordination with the United States, United Kingdom, Norway, Canada, Türkiye, and other like-minded countries in the EU’s neighborhood, including Ukraine. It also extends to strategic Indo-Pacific partners such as Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. In addition, it highlights the critical role of NATO–EU coordination in strengthening European security, and makes clear that EU-level efforts can help NATO’s European members meet defence goals set by the Alliance.

Crucially, the White Paper identifies seven priority areas for further capability development:

- Air and missile defence

- Artillery systems

- Ammunition and missiles

- Drones and anti-drone systems

- Military mobility

- AI, quantum, cyber, and electronic warfare

- Strategic enablers and critical infrastructure protection, including strategic airlift, air-to-air refuelling, maritime domain awareness, and space asset protection

Many of these priorities are informed by lessons learned from Ukraine’s wartime needs and the EU’s recognition that it must reduce dependence on US-provided capabilities. While this ambition is commendable and well-intentioned, a full replacement of US capabilities in the short- to mid-term is neither realistic nor feasible.

According to the International Institute for Strategic Studies report “Defending Europe Without the United States: Costs and Consequences”, the EU would need to spend at least $1 trillion to replace key assets currently provided by the US through NATO. Such a transformation faces immense obstacles, to start with the lack of available funding, insufficient political will, and divergent security perceptions across EU Member States. These conditions explain why, in light of both legal limitations and national sovereignty vs security, the EU may need to rely on “coalitions of the willing” to begin partially replacing US-provided capabilities.

Among the seven capability areas outlined in the White Paper, certain strategic enablers could be prioritized for phased replacement. Financing this step could be supported through new EU instruments introduced under the ReArm Europe Plan, innovative financial tools, and loan mechanisms such as the newly adopted Security Action for Europe (SAFE). This effort is also supported by the creation of the EU–Ukraine Task Force on Defence Industrial Cooperation.

Overall, the EU’s evolving defence and security architecture provides a solid framework to reduce its dependency on US commitments and rebalance burden-sharing across the transatlantic space. However, good strategies do not always translate into implementation. Many of the challenges outlined above remain unresolved. Therefore, there is a strong need to develop a collaborative and unifying Comprehensive Road Map endorsed by the EU, NATO, the US, and their partners. This document should define how all these important actors can jointly navigate the shifting power dynamics between the US and China while maintaining the pressure on Russia and supporting Ukraine. Such a Road Map should also incorporate the perspectives and contributions of key partners-particularly Ukraine, the UK, Norway, and Türkiye.

The EU’s evolving defence architecture offers a pathway not to replace the United States, but to recalibrate the transatlantic partnership around a more resilient and capable Europe. This shift would allow Washington to responsibly rebalance toward other regions without jeopardizing NATO’s eastern flank. If the US recognizes and supports Europe’s current trajectory into the defence domain, it can help stabilize transatlantic relations and avoid chaos in European security, particularly in the event of a sudden, uncoordinated US withdrawal from the continent. Moreover, deeper EU–Ukraine integration in defence production and operational planning could unlock opportunities for US industry as well and strengthen allied deterrence across both European, the Middle East, Indo-Pacific theatres, and elsewhere. For American policymakers, supporting this evolution is not a concession-it is a strategic investment in the future of a stronger, more sustainable transatlantic partnership.

The next section of this analysis explores Ukraine’s evolving role in European defence, the benefits of closer EU–Ukraine defence cooperation, and the ways in which joint production and integration could help the EU make real progress toward strategic autonomy while still preserving the central role of the US in European security.

Ukraine as the Vanguard of European Defence: Integration, Innovation, and the Strategic Resilience of Its Defence Sector

Ukraine’s integration into various defence-oriented cooperation formats, alongside other non-EU states, represents a crucial milestone and strategic necessity in the effort to build a common European defence, manufacturing base, and joint procurement ecosystem. In this context, Ukraine is not merely a beneficiary but an active contributor to a more secure and protected European and transatlantic space. This is largely thanks to the vibrant, resilient, and increasingly innovative defence sector it has built throughout Russia’s full-scale invasion.

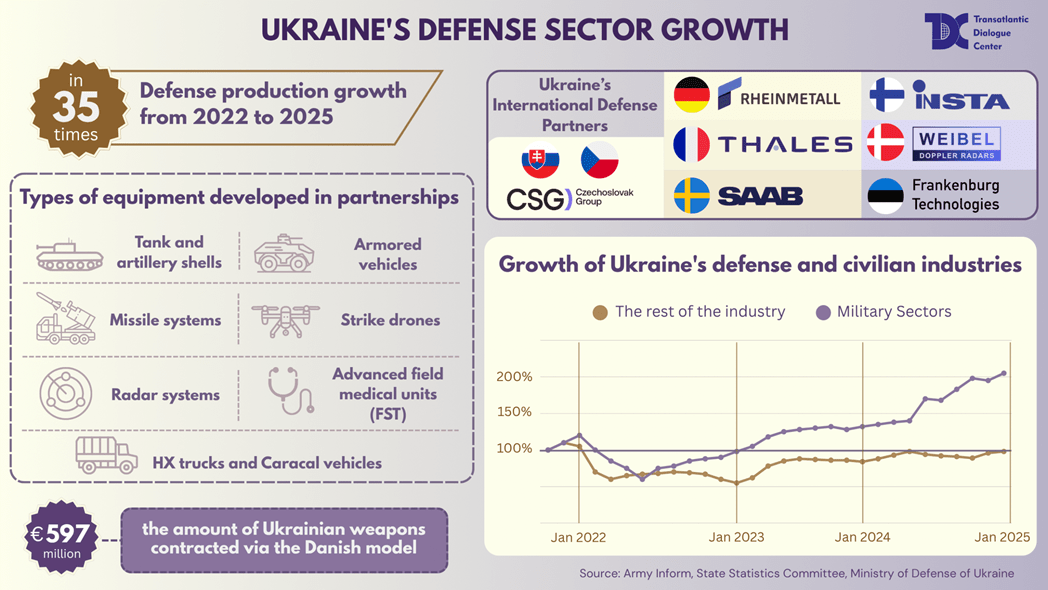

While not without challenges, Ukraine’s defence sector has demonstrated consistent growth and tangible potential to further ramp up its capacity. For example, defence production has grown 35 times between 2022 and 2025. This scale-up has been driven by two key factors: the sustained demands of high-intensity warfare and the uncertainty created by the limited capacity of Europe’s defence industry to meet Ukraine’s wartime needs, as well as the experience of stalled military aid in the US Congress in 2024.

Russia’s war against Ukraine has made clear that quantity does not always equate to quality, but quantity still has a decisive effect on the battlefield. In this regard, Ukraine achieved critical results between 2023 and 2024 in the domestic production of mortar and artillery ammunition, ranging from 60mm to 155mm calibres. Output grew from 1 million to 2.5 million rounds annually, representing a 150% increase by 2024.

Drone production has also grown steadily. As of October 2024, President Volodymyr Zelenskyi announced that Ukraine’s defence sector had surpassed 2 million drones produced annually, with a new target of 4 million drones set. This is a solid achievement, particularly considering that Ukrainian drones are constantly being upgraded for better protection against electronic warfare, extended range, and overall battlefield performance. These improvements allow drones to complement and, in some cases, replace long-range missile capabilities-while remaining cheaper and more adaptable.

Importantly, the progress is not limited to aerial drones. Ukraine has also significantly advanced the design and deployment of maritime drones, which have repeatedly proven their effectiveness in asymmetric warfare. These capabilities are relevant not only to Ukraine, but also to Europe and the US in light of their broader military engagements and deterrence strategies-especially in scenarios such as a potential conflict over Taiwan.

In terms of artillery platforms, Ukraine is approaching the point at which it can meet its own front-line requirements, thanks to the 2S22 Bohdana-Ukraine’s first NATO-calibre (155mm) self-propelled howitzer. Monthly production increased from approximately six units in 2023 to over twenty units per month by 2025.

The continued success of Ukraine’s defence-industrial expansion hinges on additional financing, which is precisely where the EU (and potentially the US) can step up. The Union’s evolving defence cooperation frameworks and mechanisms can not only support Ukraine’s domestic production but also bring Ukraine closer to the EU in the defence domain-while simultaneously contributing to Ukraine’s post-war recovery and long-term economic growth.

Deepening EU–Ukraine cooperation would allow both sides to reduce dependency on the US supply. This goal aligns with the EU’s defence priorities laid out in the White Paper for European Defence – Readiness 2030, and benefits from the growing interest of European defence firms in establishing joint ventures with Ukrainian enterprises.

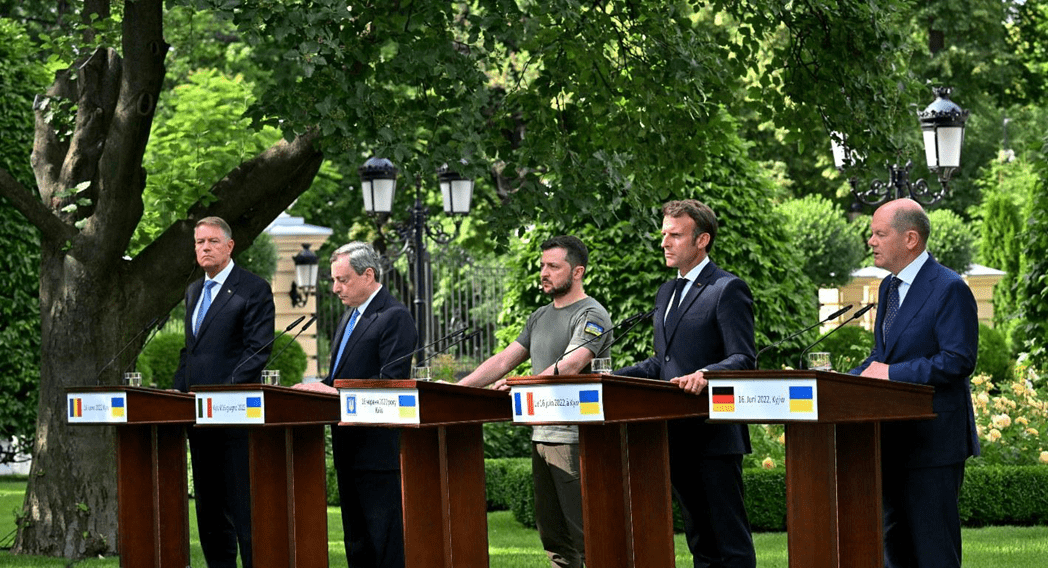

For example, Rheinmetall und Czechoslovak Group (CSG) are collaborating with Ukrainian companies to jointly produce 155mm artillery shells in Ukraine. Similarly, Germany’s Krauss-Maffei Wegmann (KMW) and France’s Nexter Systems are working with Ukrainian partners to provide maintenance, spare parts, and local production of systems such as the CAESAR and PzH 2000 howitzers. These examples highlight how European industry is increasingly engaged in bolstering Ukraine’s defence capacity-and how this, in turn, strengthens European defence.

Given mutual interests in advancing cooperation between Ukrainian and European defence industries, and with new EU frameworks allowing for more active Ukrainian participation in EU defence-related projects, the EU should seize this opportunity.

Still, notable challenges remain-particularly the gap between Ukraine’s immediate wartime needs and the EU’s longer-term rearmament goals. Additional hurdles include financing constraints, legal barriers, and technical obstacles that may delay joint manufacturing and procurement efforts.

This is where the US could play a pivotal role. If Washington actively participates in EU–Ukraine defence integration discussions-and is willing to provide financial contributions, leveraging its budgetary flexibility relative to the EU-27-it could become a decisive enabler of common European defence. In such a scenario, the EU and Ukraine would need to take care of the rest: coordination, legal harmonization, planning, logistics, and ensuring the security of supply chains.

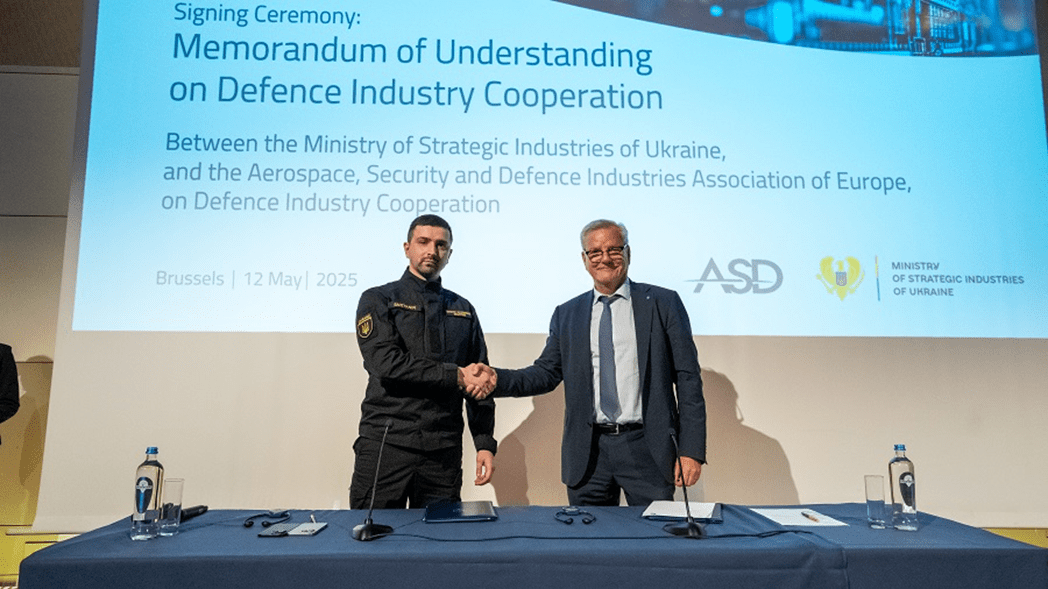

Importantly, institutional mechanisms for such collaboration already exist. Ukrainian and European defence industry representatives regularly exchange information and best practices, often facilitated by NGOs and advocacy groups. These civil society actors play an essential role in organizing visits, building mutual understanding, and enabling practical cooperation.

At the institutional level, the European Defence Agency (EDA) plays a unique and increasingly strategic role. It serves as a key facilitator and matchmaker-bringing together EU defence industries and Ukraine’s defence sector to coordinate joint procurement, integrate Ukraine into EU defence R&D programs, and support innovation through the EU Defence Innovation Office (EUDIO) in Kyiv. The EDA also addresses potential administrative and regulatory issues related to Ukraine’s participation in European projects.

One illustrative example of this role was the EU–Ukraine Defence Industries Forum, co-organized in May 2024 by the EDA, European Commission, and European External Action Service (EEAS). The forum convened key stakeholders, including HR/VP Josep Borrell and senior Ukrainian officials, and enabled direct dialogue between EU and Ukrainian defence industry representatives.

In this light, EU–Ukraine cooperation in defence is not simply a support mechanism for Ukraine-it has become a cornerstone of the broader effort to build European defence and military readiness. This partnership strengthens the security of the entire continent and positions Ukraine as a strategic asset in shaping Europe’s evolving security order.

The US must remain present in the European security architecture and actively support the integration of Ukraine’s defence sector into EU frameworks. Despite shifting global priorities, Washington has compelling reasons to maintain its role in Europe, at least in the short to mid-term, while continuing to incentivize the development of a common European defence. Doing so will help deter China and other potential adversaries, while ensuring that Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is not rewarded and that the transatlantic alliance remains strategically cohesive in the face of current and future challenges.

Conclusions: Towards a Post-American European Security Order

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine and the US’ ongoing pivot to Asia have placed Europe in a difficult position. Historically, views on strengthening European defence have varied on both sides of the Atlantic, evolving alongside shifting geopolitical conditions and power balances. The return of high-intensity war has reintroduced hard (military) security to Europe’s agenda, while the prospect of partial US disengagement has only reinforced the urgency of developing a common European defence and the capabilities required for Europe to protect itself.

What is currently unfolding in transatlantic security can rightfully be described as a transition to a post-American European security order. “Post-American” in this context does not suggest a total US withdrawal from Europe or the dissolution of NATO. Rather, it signals the acceleration of Washington’s strategic refocus on the Indo-Pacific and a shifting of defence responsibilities to European allies.

Ongoing tensions and mutual criticisms between Europe and the US are counterproductive. They risk weakening the transatlantic bond and handing a strategic advantage to adversaries like Russia and China, both of whom seek to sow discord among allied democracies. What is needed instead is deeper EU–US communication and coordinated planning around specific milestones, deliverables, and timelines for responsibly rebalancing America’s military footprint. These conversations must include Ukraine, which is not only a key frontline state but also a growing partner in European defence production and strategic planning. Ukraine’s integration into these efforts would enhance European military readiness, foster greater strategic autonomy, and strengthen the European pillar within NATO, an essential element of democratic resilience and continental security.

The foundations for the EU to become a more geopolitical and security-oriented actor are now in place. But transforming strategic ambitions into operational outcomes will require clear alignment among the US, the EU, and key partners like Ukraine. To that end, a Comprehensive Road Map outlining a division of labor for European defence development is urgently needed.

The upcoming NATO Summit in The Hague could prove pivotal. It offers an opportunity to present concrete proposals for advancing this new defence agenda and could serve as a test of whether Brussels and Washington are capable of narrowing differences and rebuilding strategic consensus. An updated Joint Declaration on EU–NATO Cooperation could serve as the vehicle to launch this much-needed Road Map.

EU leadership appears to be serious and ready to step up. In her Aachen speech, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen emphasized that Europe must craft a new form of Pax Europaea for the 21st century-one that is shaped and safeguarded by Europeans themselves. While she acknowledged NATO’s and the transatlantic alliance’s historic role in providing Europe’s security, she also declared that the era of peace dividends is over. Speaking at the European Defence and Security Summit on 10 June 2025, Commissioner Andrius Kubilius underscored that while the EU is not at war, it acts in times of war. The EU, he argued, must build up its defence readiness, revitalise its defence industry, and help construct a new European security architecture.

If the EU fails to meet its goals for defence preparedness or proves unable to sustain support for Ukraine in repelling Russian aggression, the consequences could be severe. An impulsive, uncoordinated, and chaotic US retreat from European security would harm both sides of the Atlantic. The EU, NATO, Ukraine, and other like-minded partners must therefore set aside secondary differences and cooperate on building a shared vision for the post-American European security order. If they do not, that order will be shaped instead by Russia and its allies, and Europe, if this scenario materializes, may face decades of instability, coercion, and conflict.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations with which the authors may be associated.

This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. It’s content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.