2 MB

Key Takeaways

- Environmental Destruction: Russia’s war has severely damaged Ukraine’s ecosystems, polluting air, water, and soil while accelerating biodiversity loss and climate change. The long-term consequences extend beyond Ukraine’s borders.

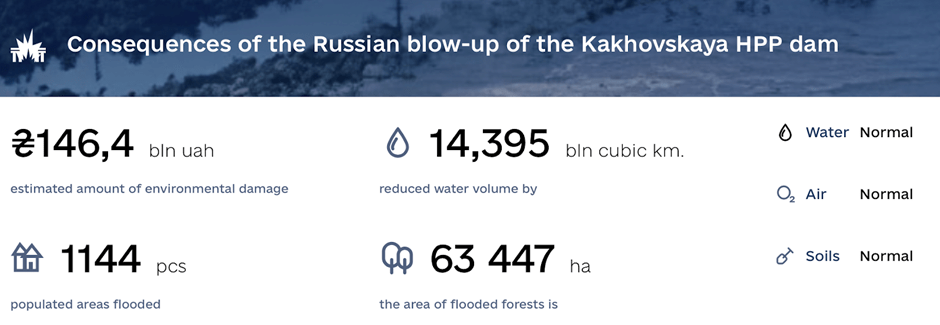

- Kakhovka Dam Disaster: The destruction of the dam caused massive flooding, contaminated water supplies, and disrupted agriculture. The resulting environmental and public health risks continue to grow.

- Landmine Contamination: Ukraine is now one of the most mined countries in the world, with vast agricultural areas rendered unsafe. Demining efforts will take decades and require significant international support.

- War-Related CO2 Emissions: Military activity has dramatically increased greenhouse gas emissions, further worsening climate change. The impact is felt globally.

- Russia’s Climate Manipulation: Moscow has exploited international climate mechanisms, falsely including Crimea’s emissions in UN reports to legitimize its occupation of Ukrainian territories.

- Weak Legal Framework: Ecocide is not recognized as a distinct international crime, limiting accountability for environmental destruction during war. Existing laws fail to address the scale of the damage.

- Ukraine’s Documentation Efforts: Ukraine is systematically recording environmental war crimes and advocating for ecocide to be included in the Rome Statute. These efforts aim to ensure long-term justice and reparations.

- Accountability and Legal Reform: Stronger international legal mechanisms are needed to hold Russia accountable for ecocide, prevent further environmental destruction, and secure compensation for damages.

Air polluted by rocket emissions, soil scarred by mines, forests consumed by flames, and water poisoned by chemicals — this is but a fraction of the environmental devastation brought about by Russia’s aggressive war against Ukraine. Along with blatant atrocities perpetrated against the Ukrainian people, Russia has unleashed unthinkable ecological catastrophes. Though often described as a silent victim of war, Ukrainian nature is on the brink of crying out over its pain and suffering.

War-Driven Exacerbation of the Triple Planetary Crisis

The triple planetary crisis — encompassing biodiversity loss, pollution, and climate change — has already been affecting Ukraine, as elsewhere on Earth. However, Russia’s full-scale invasion has significantly exacerbated the existing environmental issues and has given rise to new ones.

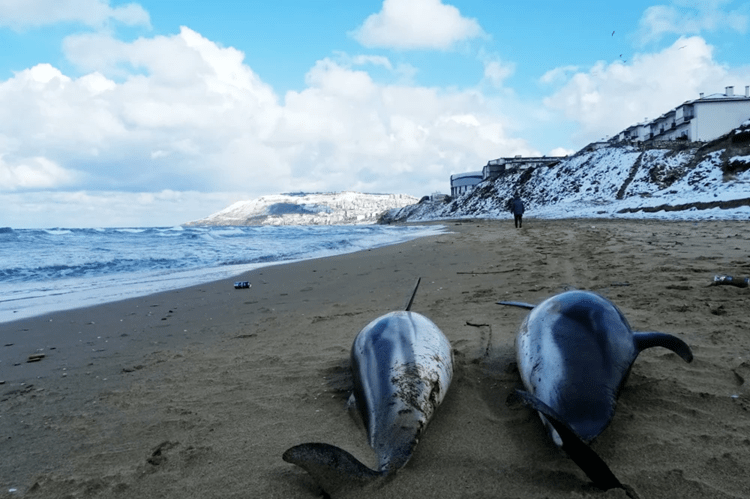

Home to 35% of Europe’s biodiversity, Ukraine is facing an aggressor state whose war crimes take a devastating human toll while also causing the destruction of flora and fauna. Approximately 600 animal species and 750 types of plants and fungi, enlisted in the Red List of endangered species, are now on the brink of extinction due to the full-scale war. And it is not only Ukrainian animals that fall victim to hostilities — numerous dolphins are dying in the waters of Bulgaria, Romania, and Turkey due to the radar systems of Russian submarines, which disrupt the marine ecosystems of neighboring countries. Thus, the role of the EU states and Black Sea countries, in particular, is invaluable in helping Ukraine document and assess the incurred environmental harm.

A largely industrial economy, Ukraine hosts numerous coal mines, chemical plants, and industrial factories. When attacked, these facilities release toxic components, polluting water, air, and soils. Russia has been deliberately exploiting this method of inflicting environmental damage on Ukraine, jeopardizing farming activities and posing significant long-term human health risks. The destruction of power facilities in eastern Ukraine has led to flooding of coal mines, further contaminating groundwater. The bombing of urban areas has resulted in widespread air pollution, exemplified by Russia’s targeting of fuel storage in Chernihiv, Borodianka, Vasylkiv, Rovenky, and Mykolaiv. Ukraine’s capital often ranks among the most polluted cities in the world, with air quality periodically deteriorating due to the release of combustion products from Russian attacks. Being constantly exposed to war-induced air pollution, Ukrainians are at risk of developing long-term inflammatory chronic diseases, which underscores a lasting humanitarian toll of environmental destruction.

The last but not least component of the triple planetary crisis — climate change — is significantly exacerbated by greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions stemming from anthropogenic activity. CO2 emissions tend to surge dramatically throughout every stage of the war, including preparation and accumulation of troops, weapons production, mobilization of human resources and equipment, displacement of refugees, and the post-war reconstruction of war-torn regions. During the first 24 months of the Russian aggression, war-related CO2 emissions amounted to 175 million metric tons, incurring an estimated €30 billion in climate-related damage reparations for the aggressor state. Given the protracted nature of the conflict and the potential for exponential growth in CO2 emissions, the international community must act in line with the 13th UN Sustainable Development Goal on climate change by bringing Russia to account for its war-related emissions.

Moreover, Russia has been exploiting global environmental mechanisms, such as the National Inventory Report of greenhouse gas emissions under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, to legitimize its illegal occupation of Ukrainian territory. Since 2015, Russia has included emissions from Crimea in its reports. Such politicization of the international system of mitigating global warming should not be tolerated. As argued by the Ukrainian delegation at COP29 in Baku, this manipulative practice violates Ukrainian sovereignty and risks providing unreliable and duplicate data on GHG emissions, breaching the integrity of the global climate change regime.

Bringing states to accountability for their war-related contributions to climate change is a challenging task due to the transboundary nature of CO2 emissions and the difficulty of proving a direct causal relation between the aggressor’s actions and global climate change progression. However, by establishing a robust methodology to quantify war-related GHG emissions and creating a legal framework to claim reparations for climate change-related damage, the international climate change regime can be extended to address both peacetime and wartime emissions. In the case of Ukraine, it is critical to ensure that any mechanism for reparations for environmental damage includes climate change-related damages, particularly GHG emissions. Russia must pay for its military contributions to atmospheric pollution, which not only endangers Ukraine but also disproportionately affects Global South countries — the most vulnerable to climate change. The UN Compensation Commission established following the 1991 Iraq war against Kuwait and the subsequent payment of environmental reparations for oil spills into the Persian Gulf can serve as a reference point for any future mechanisms for Ukraine.

The Crime of Ecocide

For centuries, nature has been targeted in wars, whether deliberately, such as scorched-earth campaigns, weather warfare, or as “collateral damage.” The war in Ukraine is a stark example of this, yet the world still does not attach sufficient importance to environmental war crimes. Given the extensive environmental concerns shaping European discourse and the narratives of many Western politicians, it seems paradoxical that crimes against nature have not yet been addressed in the statutes of international courts. While the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court has jurisdiction over four core crimes[1], it does not address environmental crimes as a distinct category. There is only one explicit mention of the environment in the document, under the section on war crimes. Still, the vague definition of what exactly constitutes “widespread, long-term, and severe damage” to the environment, its high threshold[2], and its juxtaposition with potential military advantage is counterproductive for sufficient protection of nature during hostilities.

Coined in the 1970s, the term “ecocide” has since been discussed among international lawyers and eco-activists, who advocated for its official recognition as “unlawful or wanton acts committed with knowledge that there is a substantial likelihood of severe and either widespread or long-term damage to the environment…” This definition was proposed in 2021 by the Independent Panel of Experts convened by the NGO “Stop Ecocide” for inclusion in the Rome Statute, facing expected backlash from large corporations. The campaign has also been championed by small island states — Vanuatu, Fiji, and Samoa — which can potentially become the first victims of the devastating consequences of climate change.

In 2024, Belgium became the first EU country to officially criminalize ecocide in its new Criminal Code. In several European countries, bills aiming at criminalizing ecocide have also been introduced, including in France, the Netherlands, and Spain. The EU is advancing in this direction with the adoption of the 2024 EU Environmental Crime Directive. Following the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam in June 2023, Ukraine is at the forefront of advocacy for ecocide to be recognized as an international crime.

Ukraine has already recognized the crime of ecocide: in 2001, it was incorporated into the Criminal Code under Article 441, opening prospects for domestic prosecution. It is defined as the “mass destruction of flora and fauna, poisoning of air or water resources, and also any other actions that may cause an environmental disaster.” Currently, Ukrainian prosecutors are working on 14 cases officially classified as ecocide, including one for the attacks on the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology. However, the total number of criminal proceedings of Russian war crimes against the environment exceeds 200. Notably, all information on environmental war crimes is meticulously documented to be further included in the Register of Damage for Ukraine, created under the auspices of the Council of Europe, to facilitate potential reparations. Ironically, Russia’s Criminal Code also recognizes the crime of ecocide, containing a nearly identical definition, which starkly underscores the aggressor state’s hypocrisy. Thus, more resolute international measures are needed to achieve the inclusion of ecocide in international criminal law or to draft an ecocide convention, ensuring that atrocities against nature do not go unpunished and preventing aggressor states from manipulating the environmental agenda.

The Concept of Reverberating Effects

One of the fundamental principles of International Humanitarian Law (IHL) is the principle of proportionality, which restricts acts of warfare that would cause harm deemed excessive and disproportionate to the anticipated military advantage of the attacking party. This principle is inherently subjective, as it is in the hands of the military commander to decide whether the expected advantage of the planned operation justifies the inflicted damage. Applying this strategy often leads to the omission of a very critical consideration. Proportionality calculations are usually based on the potential direct and immediate damage, disregarding the long-term consequences inextricably linked to the attack — the so-called “reverberating effects.” In the case of Kakhovka Dam destruction, these effects manifest in wildlife destruction, soil contamination, and long-term health issues. Similarly, widespread landmine contamination puts the Ukrainian economy and agriculture at risk, which, in turn, jeopardizes global food security. If reverberating effects are taken into consideration alongside the immediate damage, the blatant and highly disproportionate nature of the Russian ecocide in Ukraine becomes even more evident.

Kakhovka Dam Destruction

Regardless of the absence of a separate crime of ecocide in international law, the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam by the Russian forces constitutes a severe violation of IHL under Article 56 of Additional Protocol I, which prohibits attacks on a range of installations, including dams. Disregarding the provisions of the Geneva Conventions, Russia is deliberately targeting strategic and potentially dangerous infrastructure, such as the attacks on the Pechenihy and Oskil dams in the Kharkiv Region and the prolonged occupation of the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant. Improper management of the facility by the occupiers could lead to a nuclear accident at the plant, entailing enormous human and environmental costs that would extend far beyond the Ukrainian borders.

In the first few days after the Kakhovka Dam blowup, a number of states denounced the attack as a horrifying environmental catastrophe, but so far, only Ukraine has labeled it as an act of ecocide. Interestingly, the analysis of the international community’s reactions revealed that the most vocal condemnations came from Eastern European capitals and some Balkan countries, while the rest preferred to adopt a more neutral tone, avoiding finger-pointing.

One of the largest reservoirs in Europe, which provided drinking water for over 700,000 people, it is now referred to as the “dead sea” by Kherson region residents, who directly face the detrimental consequences of this Russian strategy of weaponization of water. The destroyed hydropower plant (HPP) played a vital role, serving multiple purposes: providing cooling water for the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, irrigating agricultural land in southern Ukraine, and generating power. Along with the disruption of these crucial processes and the increased risks of nuclear disaster, it also triggered a cascade of long-term environmental, social, and economic issues.

The widespread flooding caused by the ruination of the Kakhovka HPP prompted the transmission of toxic materials, industrial wastes, sewage, and dead wildlife, contaminating the Black Sea region — something Ukrainian authorities described as a “garbage dump and animal cemetery.” Such disasters significantly increase the risks of waterborne diseases, including cholera, diarrhea, typhoid, and hepatitis A, prompting severe public health concerns. Moreover, the floods affected many of Ukraine’s natural reserves, some of which belong to the Emerald Network — areas protected under the Bern Convention on the Conservation of European Wildlife and Natural Habitats. Almost 600,000 hectares of agricultural land are at risk of turning into deserts due to the lack of water resources for irrigation.

One of the most dangerous consequences of this blatant act of ecocide is the widespread displacement of landmines. Large portions of land are now suspected to be contaminated, which may subsequently lead to the abandonment of croplands and significant agricultural losses.

Landmine Contamination: Food Security under Threat

It is not uncommon to come across newspaper reports stating that Ukraine has become the most mined country in the world. The most recent estimates suggest that 139 thousand square kilometers of land are still suspected to be contaminated — an area roughly equivalent to the size of North Carolina or three times the size of Switzerland. Landmines and other explosive ordnance not only inflict immediate harm to human life but also create reverberating effects that persist for decades, even centuries, after peace deals are signed and arms are laid down.

Home to ⅓ of the world’s most fertile soil, Chernozem, Ukraine depends on agriculture for its economy and provides vital resources to Europe and countries of the Global South. However, as soil samples taken from the liberated Kharkiv region show, due to constant shelling and mine-laying, the earth is heavily polluted with toxic elements, such as mercury and arsenic. With an estimated 500,000 hectares of agricultural land in need of demining, the future of Europe’s breadbasket is at risk. Still, even amid widespread humanitarian and environmental catastrophe, Ukraine is exerting all efforts to prevent a global food crisis, delivering goods to areas largely dependent on Ukraine’s agriculture, such as Mozambique, Syria, Djibouti, and Palestine.

However, even subsequent demining activities aimed at releasing land and bringing it back to productive use are not always environmentally friendly. To prevent soil erosion, loss of fertility, and localized pollution, humanitarian mine action strategies should consider local environmental conditions and align with International Mine Action Standards. The Ukrainian Mine Action Strategy, launched in June 2024, addresses these environmental considerations, which are to be further incorporated into the activities of several demining operators. Support from partners is of utmost importance, given that the overall budget required for the demining of the Ukrainian territory is estimated at approximately $37.5 billion.

Eco-Devastation: Russia’s War on Ukraine’s Natural Reserves

Russia has been targeting Ukrainian natural reserves since 2014, and today, over 500 nature reserve sites are under occupation and more than 800 are relentlessly damaged, including wetlands protected by the Ramsar Convention and conservation areas of the Emerald Network. At least eight UNESCO biosphere reserves are located in Ukraine, with two of them being under the brutal Russian occupation. They are also among the largest and most well-known in Europe — Askania Nova and the Black Sea (Chornomorsky) reserves. The former is considered the oldest steppe in the world and is home to over 3000 animal species, many of which are rare and endangered. Yet the occupational power, established in spring 2023, does not make any efforts to preserve the unique natural diversity. Instead, they began using heavy equipment and digging trenches in Askania’s virgin and pristine steppes.

Numerous reports reveal that Russia is also engaged in the illegal deportation of Red Book animals from the reserve to the temporarily occupied Crimea, as well as the aggressor state’s territory. Threatening these species’ survival is a gross violation of international agreements, including the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), of which both Ukraine and Russia are signatories.

Moreover, many of the natural parks and forests are constantly suffering from fires caused by military actions or deliberate sabotage. For example, during the Russian presence in the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve, the occupiers deliberately prevented fires from being extinguished by blocking the work of firefighters. The biosphere reserve around the Kinburn Peninsula has suffered at least 449 forest fires due to ongoing hostilities. The fires have also destroyed the totality of the protected area of Dzharylhach National Park.

The Role of the International Community

Ukraine is a pioneer in documenting environmental war crimes and is seeking to establish a global standard for the investigation of ecocide. Even though environmental crimes could also be prosecuted under the framework of war crimes or genocide—particularly if environmental destruction causes widespread loss of life—such provisions remain human-centric rather than nature-centric. The role of the international community should consist of devising a legal mechanism for bringing perpetrators of ecocide to accountability.

One potential prospect is the aforementioned incorporation of ecocide as a distinct crime under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, of which Ukraine became the 125th member on January 1, 2025. This would open avenues to prosecute individual perpetrators, including political leaders and military commanders, for any future acts of ecocide, as the ICC cannot retroactively prosecute previously committed crimes.

A distinct and unambiguous definition would also ensure that environmental crimes are addressed not only as components of war crimes, requiring a high threshold of violence and awareness of consequences, but also as standalone offenses committed in peacetime. Moreover, states that ratify a new provision recognizing ecocide as a crime could potentially prosecute perpetrators under the principle of universal jurisdiction. Reforms can also be introduced to international humanitarian law, providing a more detailed definition of ecocide in the Geneva Conventions and setting a higher threshold for proportionality calculations, including environmental reverberating effects. Ukraine could also seek an advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice through the UN General Assembly resolution to clarify the current international law regarding environmental war crimes.

Recognizing ecocide as a distinct crime would also open up prospects for reparations for victims, especially in light of Ukraine’s extensive efforts in documenting environmental damage, including through the EcoZagroza platform developed by the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources. In line with the Environmental Compact for Ukraine, a specific methodology for collecting information and subsequent quantification of the damage should be developed with the help of international experts to be further included in the Register of Damage for Ukraine.

Conclusion

Ecocide is a crime that seeks to steal the planet’s future. In contrast with some other war crimes, it transcends borders and time, so its recognition internationally is vital for ensuring that nature killers are not left unpunished. The world should not leave Ukraine alone in its fight against the aggressor’s environmental crimes, as this support extends not only to the protection of Ukraine’s natural heritage but also to the salvation of the global environment and climate for future generations.

[1] Genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and crime of aggression.

[2] High threshold refers to the cumulative nature of the definition: it requires the damage from the act to be simultaneously “widespread, long-term AND severe.”

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations the authors may be associated with.