2 MB

Key Takeaways

- EU Energy Dependence on Russia: The EU remains vulnerable due to its reliance on Russian fossil fuels, which finance the ongoing war in Ukraine. Achieving full energy independence from Russia is crucial for European security.

- Progress in Energy Diversification: The EU has shifted its stance, reducing gas usage and forming new partnerships with the US, Norway, and Qatar. However, complete detachment from Russian energy, particularly LNG, remains slow and complex.

- Green Transition as a Strategy: The green transition is seen as essential for both climate goals and energy security. However, new dependencies on critical minerals from unstable regions pose emerging risks.

- Ukraine’s Potential Role: Ukraine’s gas storage capacity and lithium reserves offer strategic opportunities for EU energy security, but infrastructure risks and geopolitical challenges limit immediate gains.

- Urgency of Action: Continued reliance on Russian energy weakens Western support for Ukraine. The EU must accelerate the transition to renewables and secure reliable partners to ensure energy independence and broader geopolitical stability.

Russia has been waging a full-scale war against Ukraine for three years now. The democratic states of the West are united in their support of Ukraine, providing various types of aid. While unprecedented sanctions were imposed on Russia, energy remains the weak spot of the EU due to its dependence on Russia’s energy supplies. It is not yet clear how quickly its members will be able to disconnect from it. Thus, the energy trade that some EU countries continue to engage in huge volumes still finances Russia’s military machine.

As analysts aptly note, aid to Ukraine is not charity. The Russian invasion and the subsequent courageous resistance of the Ukrainian people were a watershed moment for the transatlantic security architecture, demonstrating the value and importance of Ukraine to Europe. So, refusal from Russian energy carriers is also neither an act of charity nor a noble gesture. Therefore, this article will consider the EU’s sharp shift in its stance towards Russia as an energy supplier in the context of the Russian-Ukrainian war. It will explore the challenges the European Union faces in reducing its dependency on Russia, as well as the EU’s green transition and the potential role of Ukraine in contributing to Europe’s energy security.

Evolution of the EU’s Stance on Russian Fossil Fuels

Trade in energy carriers used to be one of the points of relations between the EU and Russia. For many years, Russia has been the main supplier of oil and gas to the European Union. In addition to this EU-Russia energy trade included coal and nuclear materials. At first, this cooperation was considered by the European side as quite convenient and profitable. Geographical proximity, existing infrastructure, and Russia’s ability to export large quantities were the most important reasons why the Russian Federation seemed to be the best partner. In 2021, Russia supplied more than 45,3% of the EU’s gas consumption. Additionally, Russia was responsible for 27% and 46% of the imports of both oil and coal.

Immediately after the start of the full-scale Russian-Ukrainian war, most MEPs agreed that the EU should quickly strengthen its strategic autonomy in defense and energy. They advocated diversification of energy purchases as well as investing in renewable energy. It was finally recognized that Russia’s illegal and unprovoked invasion of Ukraine was not only an attack on the country’s territorial integrity but also a grave risk to the security and stability of all of Europe.

It appeared that after several decades of close cooperation and turning a blind eye to Russia’s ever-increasing decline into an undemocratic, authoritarian, and aggressive regime, the EU and its leaders have come to an epiphany. The war showed that the EU’s belief that economic interdependence would have a positive effect on the regime in Russia was deeply mistaken. Russia’s massive invasion of Ukraine demonstrated the risks of relying on a single supplier of fossil fuels. Since the spring of 2022, Russia has used the stoppage of gas supplies to its European consumers as a means of blackmail, attempting to force them into changing their policy towards Ukraine.

On March 8, 2022, the European Commission published the REPowerEU strategy, which aimed to reduce dependence on Russian fossil fuels as quickly as possible. Through negotiations, member states reached a consensus on a 15% reduction in natural gas use. From August 2022 to January 2023, the EU managed to gain more; the Union reduced its gas usage by 19%. Later, member states engaged in more protracted and challenging negotiations regarding sanctions against Russian oil.

In 2023, the US and Norway became the top gas suppliers to the EU. Nearly 30% of all the EU’s gas imports came from Norway. Qatar, the UK, and countries in North Africa are further providers. This exploration has the potential to have negative impacts that include physical disruption of environments important for marine biodiversity and pollution. Nevertheless, in the near future, increased attention is expected to be paid to hydrocarbon production in this area. Moreover, in 2022, Norway decided to extend coal mining in Svalbard until 2025, as the Norwegian Minister of Industry stated that coal is used for steel production in Europe.

When New and Old Problems Come Together

As of 2022, EU members found themselves in very different conditions regarding the energy situation. Dependence varied greatly, which started to create and still creates problems for the EU. Unfortunately, despite the quick reaction, the actions of the EU were not so immediate. The complete elimination of the EU’s dependence on Russian oil and natural gas is a long-term goal for the EU.

| Not dependent | Dependent to some extent | Dependent to a large or total extent |

| Belgium, France, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden | Italy, Germany, Greece, Finland, Romania, Poland and Lithuania | Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Slovakia |

In 2023, gas from Russia accounted for 15% of the total gas purchased by the EU, which, compared to previous indicators, is a real achievement. At the same time, in May 2024, the EU was the fourth-largest buyer of Russian fossil fuels, accounting for 13% (€1.9 billion) of all Russian gas exports. Piped gas accounted for the largest share of EU fossil fuel purchases in Russia (45%), followed by LNG (27%) and pipeline crude oil (22%). The three largest buyers of Russian energy sources were Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic (crude oil and pipeline gas). The EU has continued importing and reselling Russian LNG, which is transported by tanker in supercooled liquid form. This situation has become a significant embarrassment for the bloc. Spain, France, and Belgium were the largest buyers of Russian LNG in the past year.

The country widely recognized as having initiated the war in Europe and perceived as the greatest threat to the continent continues to receive substantial financial support from several European nations. Since the onset of the full-scale Russian-Ukrainian war, the Czech Republic’s spending on Russian oil and gas has been five times higher than its financial aid to Ukraine. The diagram shows the comparison of some countries.

Made by author. Sources: CREA, Politico, Kiel Institute for the World Economy

In many cases, economic dependence, primarily energy, creates political dependence. This, in turn, can either endanger or escalate the slide of the political regime towards being illiberal and undemocratic. This, accordingly, turns such countries into centers for the promotion of pro-Russian narratives and influences, undermines political unity in the EU, and creates additional internal problems. Countries such as Hungary and Slovakia, while continuing to buy Russian fuel, also stubbornly promote the rhetoric of re-establishing economic ties with the Russian Federation at the EU level, as, in their opinion, this is the best choice for the EU.

This situation became possible because landlocked Central European countries such as Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic were given the right to continue importing Russian energy resources. While Bulgaria banned the importation of Russian oil despite its exemption from EU sanctions, the three countries mentioned above are only increasing these supplies.

Following Russian aggression, several states heavily reliant on Russian oil and gas have opposed energy sanctions, while member states less reliant have called for an immediate and rapid transition away from Russian sources. Sanctions first addressed energy only in their fifth package, adopted in April 2022, with an embargo on Russian coal, while a partial embargo on oil was introduced with the sixth package in June 2022 (with significant exemptions for some member states) and an oil price cap was only achieved in the eighth package, adopted in October 2022.

Despite efforts made by the EU to reduce dependence on Russian gas, some countries continue to receive significant volumes indirectly. Austria’s pipeline imports from Russia increased to 98%, while Russian gas is being routed through Azerbaijan and Turkey to meet EU demands. Deals with Azerbaijan entail infrastructure that is partly held by Lukoil in Russia, and the country itself depends more on imports from Russia to meet its own needs. The gas deals that Romania and Hungary have with Turkey most likely involve Russian gas. Furthermore, a few nations, including France and Austria, have long-term agreements with Russian energy suppliers.

In the end, the first sanctions on Russian gas were approved by the EU only in June 2024. However, even after that, the majority of Russia’s liquid natural gas (LNG) exports to the EU remain unaffected by the sanctions. Instead, the measures prohibit EU ports from reselling Russian LNG upon arrival and obstruct funding for Russia’s proposed LNG installations in the Arctic and Baltic.

Is Green Transition a Solution?

In recent decades, the energy transition, which is characterized by a shift from fossil fuels to renewable and low-carbon energy sources, has become an important climate change mitigation strategy. The European Climate Law sets objectives of meeting the 2050 climate neutrality objective and a 55% reduction of net emissions of greenhouse gases by 2030. The war showed not only that the EU and European countries need to choose reliable partners for the provision of strategically important resources. It showed that climate neutrality by 2050 is both a necessity to slow down climate change and a thorough way to ensure the security of the EU.

The energy security and energy sovereignty of countries are strengthened by energy transition. The EU and its member states have already expanded the use of renewable energy sources, increased energy efficiency, and moved to clean technologies, and now they need to protect and build on these successes. At the same time, in this area, the EU also has some potential problems that need to be either solved or quickly prevented.

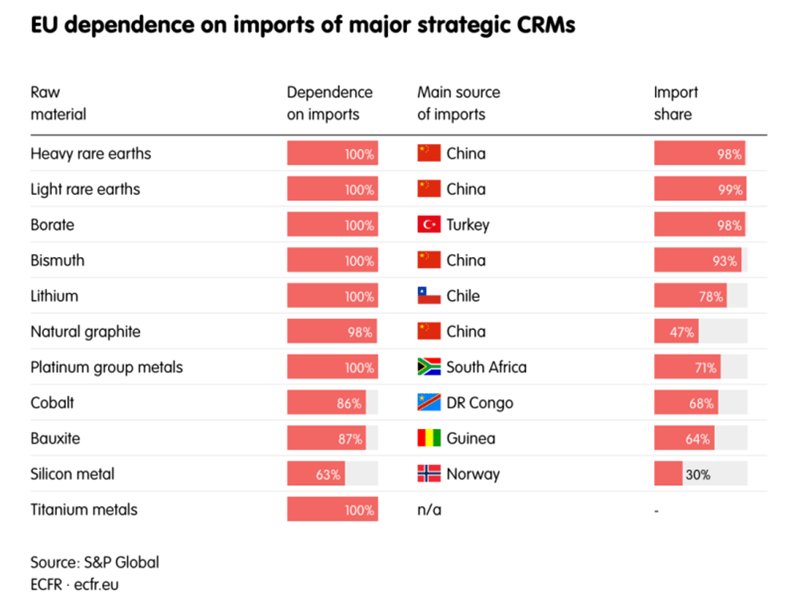

Having experience with the Russian Federation, the EU should be very careful when choosing partners for the supply of such important products. Dependence on countries supplying fossil fuels may change to dependence on countries supplying resources necessary for green energy, in particular, rare earth metals. Many countries have large mineral reserves, which are strategically important for European industry. The EU has established partnerships with Argentina, Australia, Canada, Chile, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Greenland, Kazakhstan, Namibia, Norway, Rwanda, Serbia, Ukraine, and Zambia. Looking at the chart below, we can see a huge dependence of the EU on partners that may be either affected by conflict or taking part in trade wars, primarily China, Congo, or Turkey.

Due to the growing need for a green transition, the demand for essential minerals by leading global players such as China is increasing at a tremendous rate. Vivid examples of such a race to the front are the fight for Chile or Greenland. In July 2023, the EU and Chile signed a memorandum of understanding focused on critical materials and supply chains aimed at strengthening cooperation. In December, the two sides reached an agreement on a modernized association agreement. Chile is a very attractive partner for the EU because of many reasons. It is a liberal democracy that firmly sticks to multilateralism, human rights, and international law. In addition, it has a strong desire to become a carbon-free economy.

In November 2023, the EU partnered with Greenland for critical raw materials and also opened a new office in the Greenlandic capital. Múte Bourup Egede, Prime Minister of Greenland, and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen signed two agreements. One of them focuses on investments in value chains for renewable energy and critical raw materials, with 22 million euros allocated for this purpose. The second agreement relates to cooperation and investment in education, for which the EU provides 71 million euros. The EU’s interest in Greenland, as Ursula von der Leyen’s speech showed, has two reasons: Greenland has sought-after raw materials and a geostrategically important location.

(Nov 2021 – Nov 2022)

Another reliable and almost ideal partner in the EU’s green transition could be Norway. In Norway, 98% of electricity is produced from renewable energy sources, and the source of most of it at the moment is hydropower. In general, the situation with this country is particularly interesting since it is now the world’s fifth oil exporter and the world’s third natural gas exporter. As mentioned earlier, it is currently the leading supplier of gas and oil to the EU. However, with a huge potential to increase, it aims to become a green power plant for the EU. This country is a pioneer in carbon capture and storage research and is also investing in battery manufacturing, hydrogen and pure ammonia projects, and renewable energy technologies such as offshore wind and solar panels.

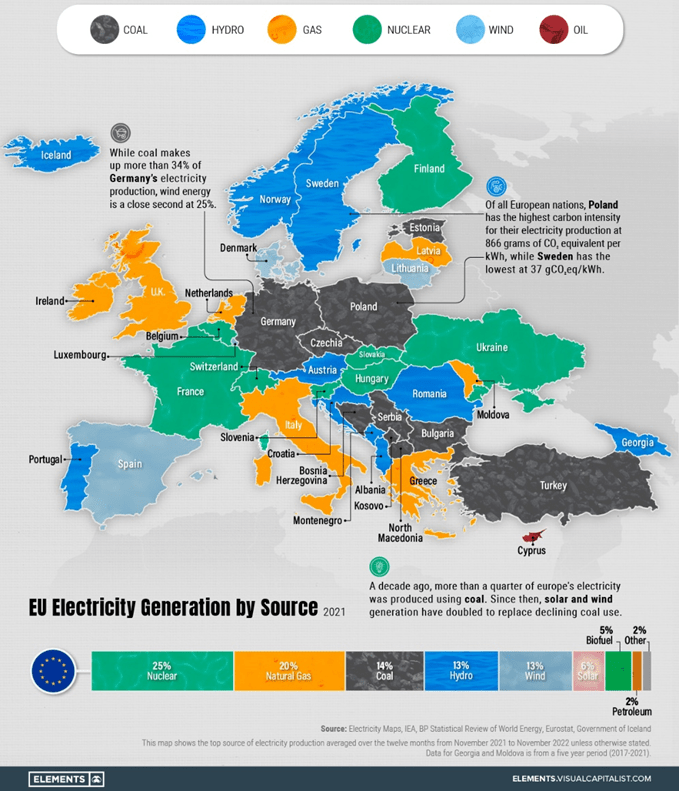

It is also worth mentioning some other problems that the EU faces on the way to achieving zero carbon emissions. Of course, each member country has its own ratio of energy carriers in the production of electricity. In particular, the main source for Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, and Slovakia is gas; for Poland, the Czech Republic, and Estonia – solid fuel; for France – nuclear; renewable sources occupy the largest share in Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Latvia.

Member states started to re-evaluate their energy policies in order to find domestic reserves that would allow them to improve their own energy security. While some countries focused on doubling down on renewable energy sources, energy efficiency, and other measures with the potential to reduce the share of fossil fuels in the EU’s energy mix, several member states, being in a critical situation, had no other choice but to choose coal as a suitable solution. For example, Germany restored a significant capacity of coal-fired electricity generation. Austria, the Czech Republic, and the Netherlands also started considering coal as a crucial energy security element.

EU countries with substantial fossil fuel reserves should not be allowed to rely on these resources indefinitely under the assumption that it ensures their energy independence and security. This creates the risk that some countries would begin not to diversify their energy sources but just replace them with similar or even greater polluters of the atmosphere. It can become a reality for Poland, where in 2022, thanks to domestic reserves, 70% of electricity was generated from coal, and the conservative government was clearly not very ambitious about the transition. However, in the first seven months of 2024, this country demonstrated very positive results. Thanks to the arrival of the new government of Donald Tusk, the situation began to change rapidly, and in July, the share of coal reached a monthly minimum of 53%. It is interesting how the situation with electricity in this country will develop in the future, as the previous administration’s procrastination on climate action will definitely complicate matters. In addition, the Polish energy and climate research group Forum Energii recently disheartened that the country’s energy transition is still largely driven by market forces and reforms that remove barriers to clean energy developers rather than a concerted push from the state.

Following the adoption of the Climate Law and most of the ‘fit for 55’ legislative revisions, member states had to update their national energy and climate plans. The 2030 EU Climate Law target is binding at the EU level. Its achievement, however, depends on the success of plans and measures at the national level across a range of policy areas. And here, accordingly, another problem arises – the pace of the green transition in all countries is very different; for example, the countries of Eastern Europe have much lower indicators compared to the successes of Northern or Western ones. Accordingly, the EU should provide assistance to these countries that would facilitate the transition and significantly improve the overall performance of the EU.

At the same time, there were also some misunderstandings between major European countries over energy sources. Particularly, tensions between France and Germany over nuclear power. Currently, approximately 70% of France’s electricity is generated from nuclear power, and under Emmanuel Macron’s plan, it will only increase. While in Germany, this source of electricity was completely banned and still causes a lot of opposition. Additional challenges may be caused by the fact that the new European Parliament elected in 2024 is less “green” compared to the previous one, as the Green Party received 53 seats compared to the previous 70. Additionally, a lack of coordination at the EU level resulted in most agreements with new energy partners being negotiated independently by member states. As a result, some contracts for fossil fuel supplies extend until 2050 or beyond, contradicting the EU Green Deal’s objective of achieving carbon neutrality by that time.

Furthermore, environmental and climate diplomacy serve as essential tools of soft power, playing a critical role in shaping the EU’s image and influence. European integration, which began in the 1950s with a focus on coal and heavy industry to prevent wars between major European powers, now appears to come full circle. Aiming to become the first green continent by 2050, Europe will achieve energy independence and once again strengthen its security. Thus, this transformation would reflect a great and symbolic evolution.

Potential Role of Ukraine

Addressing the current situation in the EU and its members’ gas needs, Ukraine has the potential to play a significant role in enhancing Europe’s energy security. Ukraine’s position offers an opportunity to help Europe reduce its dependence on Russian energy supplies. With the largest underground gas storage facilities in Europe, Ukraine even provided valuable storage capacity for EU companies last year. Currently, Europe’s gas storage facilities are over 90% full. “We can offer our partners enough free space in Ukrainian storage facilities to store their gas,” stated Oleksii Chernyshov, CEO of NJSC Naftogaz. However, the ongoing shelling of Ukrainian territory by Russia raises concerns among European partners regarding the reliability of this option. Ukraine, nevertheless, emphasizes its capacity to provide storage while stressing the need for additional measures to protect its energy infrastructure from attacks and to strengthen air defense systems.

Ukraine also possesses significant reserves of lithium, a key metal for the green transition, holding up to 10% of global reserves, according to estimates. Yet, challenges persist. The lithium deposits are primarily located in eastern Ukraine, with some in areas currently occupied by Russia. Additionally, due to the unique nature of Ukrainian lithium deposits and the lack of global technologies for extracting lithium from similar ores, Ukraine will be unable to produce lithium products or sell ore concentrate in the near term. Nonetheless, these reserves are likely to hold considerable strategic importance in the longer term.

Conclusion

The persistence of Russian fossil fuels in the European Union presents a major obstacle to both energy independence and geopolitical stability. As the EU grapples with the repercussions of the war in Europe, severing ties with long-standing Russian energy suppliers remains complex. Decades of dependency cannot be reversed overnight. To address this, the EU is focusing on improving energy efficiency, increasing investments in renewable energy, and diversifying its energy sources by turning to West Africa, Central Asia, the USA, and Norway. While progress has been made, more efforts are needed to fully eliminate Russian energy from the EU’s supply chain.

Additionally, the continued purchase of Russian fossil fuels directly finances the conflict in Ukraine, diminishing the impact of Western aid. This makes urgent and decisive action essential. The green transition offers the only long-term solution, and its success depends on the EU’s ability to secure reliable new partners. Accelerating this transition will not only enhance Europe’s energy security but also contribute to broader geopolitical stability.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations the authors may be associated with.