796 KB

The unprovoked Russian aggression against the independent state of Ukraine continues to undermine the agreed international order. Has it ever occurred to anyone that amid the unjustified Russian aggression against the sovereign state of Ukraine, the alleged allies such as Georgia and Moldova end up playing with ‘neutrality’ while Poland and the UK enter the new security alliances? The whole world held its breath watching the unprecedented David and Goliath fight, giving birth to the new world order. It is as clear as a day that neither Mackinder nor Spykman would have imagined something like this in their most ‘heartlandish’ and ‘rimlandish’ dreams.

Eastern Europe has always been stigmatized as a bloody theatre of armed confrontations. Back in the 1990s, the post-Soviet space was considered a permanent struggle for values-based power projection. Being obsessed with its own international status and political influence, Russia started making significant inroads throughout the post-Soviet camp in the true spirit of the backward Soviet playbook. Having gone through the pendulum of uncertainty related to the choice of ideological orientation in 1991-1995, it became crystally clear that the Kremlin perceived the former Soviet members as a backbone of the Russian imperialist project ensuring Russia’s regional leadership. The latter undoubtedly deserves attention as given the prolonged ‘great-power-club’ trope embedded in the Russian society, the Russian revisionism started gradually making its inroads in Europe.

Yet, the tremendous Ukrainian resistance showed that neither ‘saving Russia’s face’ nor making any territorial concessions are the options at the negotiation table. Ukraine has all rights and satisfied justifications to liberate its territory as recognized in 1991 when Kyiv regained independence. Given the fact that Russia proceeds with turning the occupied Crimean Peninsula into a military base to project its imperialist interest to other parts of the globe (primarily to the Middle East), the upcoming Ukrainian counteroffensive and its expansion to Crimea have become a highly contested topic in some Western quarters and beyond.

This article will attend to the drivers of Russia’s hostile behavior before the full-scale invasion through the game theory lenses in order to understand what logic was driving the Kremlin as an authoritarian state facing a crisis of public confidence. Unpacking these drivers will allow the policy-makers to understand better why appeasement of Russia will never be a good strategy to pursue. Russia has been attempting to use foreign policy to legitimize the domestic political regime, making up for the inefficiency of state institutions with imaginary ‘small victories.’ This article will highlight the main facets of Russian revisionist aspirations and provide solid reasons why the West should stop Russia and help Ukraine liberate all its territories, especially Crimea.

Democracy Is Not a Given: Inculcating Tolerance for Rampant Challenges

Since the end of the Second World War, when the potential hegemon at that time — the United States — pushed the process of democratization as an effective tool for ensuring both national and international security, the international political discourse has acquired a new meaning, which has constantly been challenged by aspiring actors. In his book ‘Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch’, the outstanding German philosopher Immanuel Kant noted that ‘democracies tend to co-exist more peacefully’. Provided any absolutization is discarded, one can conclude that democracies mostly do not fight among themselves given a high level of mutual trust. In fact, it fits into the assumption that homogeneous systems of international relations are less prone to conflicts, which became the backbone of the ‘messianic’ vector promulgated by the US. Basically, this logic implied that to reduce the confrontation in the world, other actors must be democratized.

In this context, it is no less important to supplement this canvas with other factors that testify to why democracy became possible and even necessary in general, and, as a result, became entrenched in the international political discourse being challenged by revisionist actors like Russia. From the retrospective standpoint, one can notice that a significant shift towards democracy took place in the second half of the 20th century. This was driven by several factors, including the increase in literacy of the population, a higher education level, and the increase of the part of the population that could get access to this education, the acceleration of economic development, and, not surprisingly, laying the foundations for the revival of international cooperation. At that time, the US played a significant role in building upon the so-called rules-based order engaging itself more in international issues of the time (the Marshall Plan, the extrapolation of military potential in Western Europe). This engagement provoked social units within the state to become more heterogeneous, which required the adaptation of such a form of state management that could maximally satisfy the interests of different population strata along with fragmented elites. Democracy became a reaction to these dynamic changes (de facto society started developing much faster than state structures). The motto ‘no taxation without representation’, which became a product of the American Revolution (against the British colonialists), could be safely extrapolated to the modern coordinate system. Democracy is the only political regime known to mankind, designed to maximize the presence of the population in public affairs.

Furthermore, with the invention of the Internet and advancement in various communication systems, not only privacy but also the line between the electorate and authorities became extremely blurred. The era of the global Internet brought into the public space people who had never been there before, who earlier made up the reactive (not proactive) part of society. The transparency (or its absence) of state structures became more noticeable with the emergence of ‘Twitter diplomacy’, ‘the state in a smartphone’, ‘online elections’, etc. Even the process of public control over the actions of the bureaucracy has been intensified: corruption scandals and exposure of unscrupulous bureaucrats have become a product of increased access to information flows for most of the population. Voters became extremely invested in expressing their opinion permanently, not only while choosing new politicians every 4 or 5 years. Therefore, democracy has become a product of such a ‘l’état c’est moi’ boom, but not as Louis XIV would have imagined. The latter envisages assuming that more citizens are interested in expanding their participation in public life. This explains the current crisis of trust in government institutions being amplified by revisionist movements. In the most distorted forms, this crisis manifests itself in the spread of the phenomenon of illiberal democracies, Poland and Hungary being startling examples.

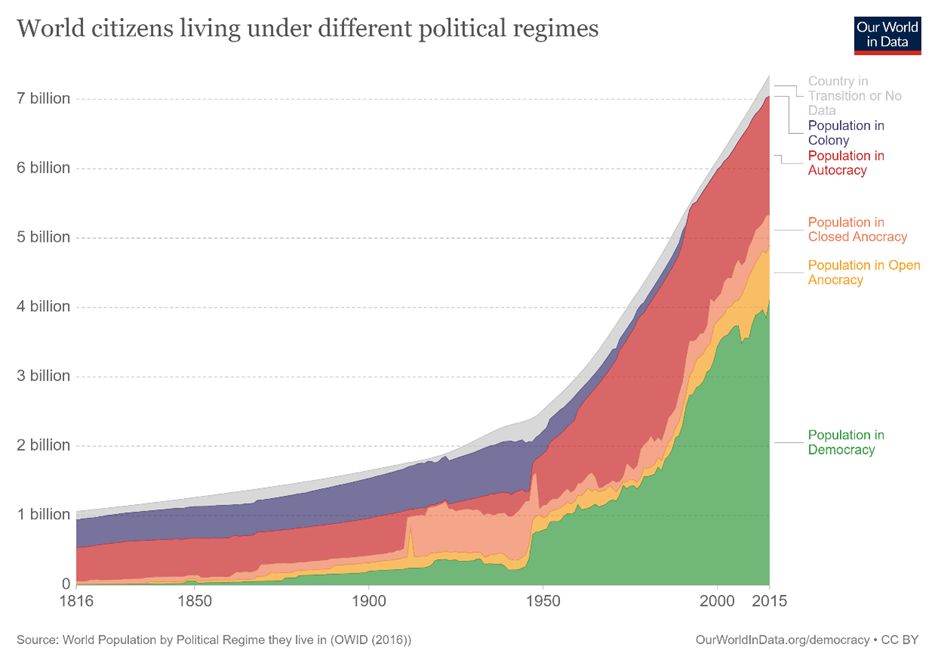

The graph shows that the acceleration of the democratization process took place at the beginning of the 21st century. The theory of democratic transit became extremely popular at that time, according to which all actors of international relations would sooner or later come to democracy in the true spirit of Fukuyama’s ‘end of history’. However, after the Arab Spring, which should have become a kind of roadmap for this democratic transit, most of the state entities picked up autocratic tendencies. Tunisia became the only example of preserving the signs of democracy (no wonder it was the Tunisian quartet that received the Nobel Peace Prize for this). This was the first warning signal that the process of democratization could be irreversible, and alternative regimes got a chance to survive in the 21st century.

In his essay on illiberal democracies, Farid Zakaria harshly criticized democratic prospects. On the one hand, it was a substitution of the term ‘democracy’ for ‘liberalism’. While the former deals with the power of people, the latter corresponds with the attitudes, values, and views these people share and respect. Therefore, the terms ‘democracy’ and ‘liberalism’ per se are situated on different coordinate systems. Democracy involves expanding the scale of the population involved in the process of state management, while liberalism creates specific rules of the game, according to which social interactions take place, and which determine the limits of state involvement in the life of an individual (and vice versa).

In the 22nd chapter of his Tao de Jing, Lao Tzu, long before Fichte and Hegel, formulated one of the fundamental laws of human evolution: no matter what, any socially constructed order having reached its development apogee becomes its opposite. It happened to the US when the insurrection on the 6th of January 2021 took place, exposing the temporary crisis of democracy and questioning the liberal order. No wonder numerous speculations on authoritarian ‘rollback’, backed by Huntington’s waves of democracy theory, became the real talk of the town. However, the following developments (including the ongoing pandemic) and the measures taken by the Biden administration (e.g. law enforcement response) did not halt the epidemic of far-right extremism as was evidenced by the rise of apologists advocating for the alternative way of international order.

Russian “Mysterious Soul” Unlocked: Democratic Image over Authoritarian Substance

Constructing the ‘Self-Other’ dichotomy, situating Russia on the one end while placing ‘the hostile collective West’ on the opposite one became the apogee of Russia’s geopolitical and ideological project. Interference with the internal affairs of other independent states (Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, Armenia) revealed the toolkit Russia was using to project its delusional influence. Advocating for Ukraine’s ‘federalization’, creating a ‘grey security zone’ in Donbas since 2014, illegal occupation of Crimea and for the time being the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, contributing to poor institutionalization with regard to the Commonwealth of Independent States were primed to back the illusions of Russia’s viability as an alternative political regime, opposite to democracy and liberalism. The concepts such as ‘sovereign democracy’ (nothing more than a simulacrum of the real meaning of democracy), ‘Moscow as the Third Rome’, and ‘Decaying (Rotting) West’ fueled the anti-American and anti-European sentiments inherited from the Soviet times.

Regarding the so-called “sovereign democracy”, we should not be under the illusion that Russia is nurturing democratic changes. On the contrary, Russian society has been tolerating its “systemic opposition” (working side by side with the Kremlin), unfair elections, and total control over social media for decades. The well-oiled machinery of Russian propaganda has been entirely legitimized by its own citizens, who show little disobedience or complete support of the Russian authoritarian internal and imperial external agenda. Given the “digital iron curtains” perpetuated by Russia, Russian citizens continue to consume propaganda-driven media products not even willing to diversify their sources of information.

Back in time, Zbigniew Brzezinski, having analyzed the threats to the national and international security of the United States, warned that the international status quo might be under attack. He noted that the most dangerous scenario would be a powerful coalition between China and Russia, which would not be united by common ideological principles, but by the desire to destroy the status quo and adjust it to their own national interests and values. According to Brzezinski, this coalition would have to resemble the Soviet-Chinese bloc in terms of its scale, although in this specific case, the ball would still be in China’s court, and Russia would play second fiddle.

Likewise, back in time, American President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser Henry Kissinger, who adhered to the strategic views of George Kennan (the doctrine of deterrence telling us that in the end nationalism prevails over communism), managed to conduct a successful diplomatic maneuver, called ‘triangular diplomacy’. The latter envisaged playing the ‘Chinese card’ (using China against the Soviet Union). Notwithstanding, the times keep changing, and for the time being we can observe playing the ‘Russian card’, yet not by the US.

Unpacking Russia’s Way of Thinking Through Game Theory

According to Russian strategic documents, creating one more ‘frozen conflict’ could have helped preserve the political influence over the key ‘satellites’ and impose pressure on other neighbors. From the neorealist perspective, states do not act independently of world politics but maneuver in the framework of the agreed international order. These musings were initially reflected in a security dilemma as first described by Thucydides. Having analyzed the causes of the Peloponnesian War between Sparta and Athens (started by Sparta), he stated that wars with negative mathematical expectations may still occur if an alternative scenario is considered worse by one of the parties. Notwithstanding, the results of the Peloponnesian War and subsequent wars following this model have proven that states opting for waging wars with these speculations lose their capacity very quickly and find themselves under unbearable international pressure.

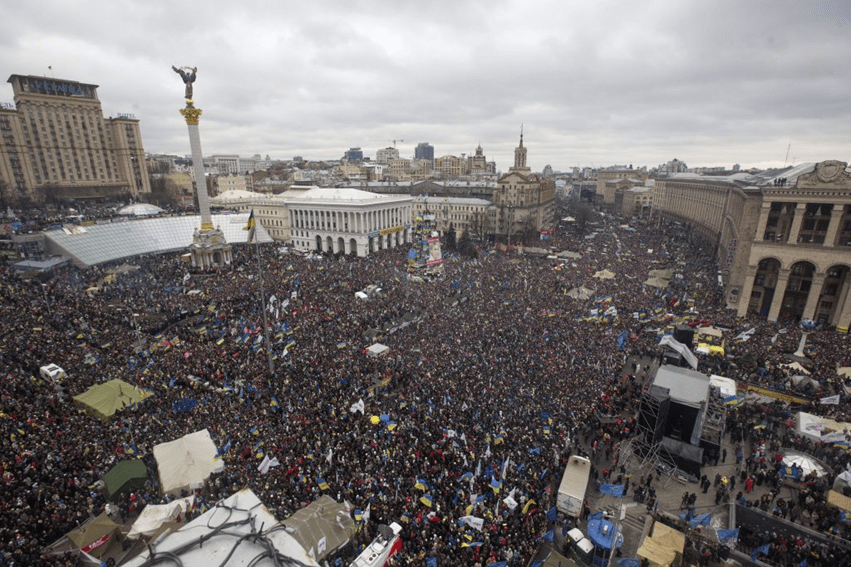

So, what became a valid reason for Moscow’s aggressive behavior? Amid the reforms that have been put into motion in Ukraine since 1991 and Kyiv’s firm adherence to democratic and liberal values, the Kremlin has been struggling to sell its ‘Russian world’ nonsense. The concrescence of business and power has been the central disease left by the post-Soviet legacy. However, the Ukrainians reaffirmed their aspirations and readiness to go to any lengths to tackle this problem by initiating and performatively participating in two revolutions – the Orange Revolution in 2004 and the Revolution of Dignity in 2013. Much effort has already been made before the full-scale invasion to reform the Ukrainian legislation framework. Since 2016, Ukraine has launched judiciary reforms, including but not limited to establishing an entirely new provision of the Supreme Court, judicial independence from the government by appointing judges via an autonomous Judicial Council, and even simplifying court procedures. Other institutions such as the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU), the National Agency for the Prevention of Corruption (NAPC), and the High Qualification Commission of Judges (HQCJ) were also put into the reform after the Revolution of Dignity. They are expected to help tackle corruption. Ukraine’s implementation of the Association Agreement has already reached 63%. The decent measures to meet the Copenhagen criteria have already been taken before unprecedented Russian aggression. The latter evidenced that the only thing Russia has been annoyed with for decades is the Ukrainian statehood and its eagerness to move forward, to keep developing and improving, using its potential to build a democratic, liberal, and prosperous country. On the eve of the full-scale invasion, Ukraine had the Association Agreement 60% completed and 54% in 2021 and 2020, respectively.

Obviously, having a powerful neighbor with such vast potential became unbearable for the Kremlin. Moscow’s decision to occupy Crimea and the Donetsk and Luhansk regions in 2014 could have only been justified if viewed as ‘the lesser of two evils’, in Russia’s perception.

This hypothesis will be analyzed herein through the game theory perspective, mainly through the so-called ‘chain-store paradox’. The chain store game involves multiple actors. The leading actor is a so-called ‘monopolist’ that deals with several ‘competitors’ in different towns. When the monopolist encounters potential competitors in each city, they have two options to choose from: opt ‘for’ or ‘out.’ The competitors conduct their activities simultaneously. Supposing the potential competitor opts ‘out,’ it gets a payoff equated to 1, while the monopolist gets a payoff equated to 5. If the competitor opts ‘for,’ it may get a payoff of either 2 or 0, depending on the monopolist’s reaction. The monopolist can choose the following reaction strategies: a collaborative one (the induction strategy) or an aggressive one (the deterrence strategy). If the monopolist opts for the former one, both players (the potential competitor and the monopolist) get a payoff equated to 2. Still, if the monopolist chooses the latter, each player receives 0 or nothing.

This game can be applied to the post-Soviet space to analyze Russia’s actions before the full-scale invasion. The Kremlin, which aspires to play a significant role in the regional system of international relations, can be seen as a ‘monopolist’. All other post-Soviet states can be considered ‘competitors’. Russia’s main task as a monopolist is to maximize its winning from asymmetric relations with competitors and remain in the orbit of its influence contrary to other players in world politics. From this perspective, Russia had two variants of interaction with post-Soviet countries:

- Escaping the ‘collaborative wreckage’ (induction theory). This path would mean Russia puts up with post-Soviet countries’ aspirations to choose their way and adopt genuine attitudes and shared values. This way entails the success of post-Soviet republics by increasing their economic effectiveness, strengthening democracy, and deepening integration into the European and Euro-Atlantic institutions. According to the chain-store theoretical framework, Russia as a monopolist and post-Soviet states as competitors would get the same benefits from the cooperation. Having chosen such a strategy for all post-Soviet states, Russia would benefit from each bilateral interaction as follows: supposing this win can be marked as 2, so the interaction with 11 republics (excluding Baltic nations from the potential satellites list as these countries have largely already managed to escape Russian influence since obtaining their independence) would bring a payoff of 2*11=22 for Russia.

- Walking into the ‘aggressiveness trap’ (deterrence theory). This approach leans on the Russian aspiration to preserve the weakness of post-Soviet states by creating significant encumbrances for them to meet the aforementioned success criteria. In the case of implementing this strategy, the monopolist has the potential to obtain higher winnings. If the monopolist created significant obstacles to the competitors’ success, both parties would not gain any benefits, so their payoff would be 0. However, if the competitor refused the aspiration to improve its effectiveness and fell short of combating the monopolist’s influence, the monopolist would gain a payoff of 5 while the competitor would gain 1. While employing the method of threatening 4 states (Georgia, Moldova, Armenia, and Ukraine, as all these countries have been invaded by Russia), Russia counted on a scenario where other states, estimating the devastating consequences of the armed conflicts, would deliberately refuse the idea of escaping the Russian influence. Russia seeks to use ‘grey security zones’ — creating the frozen conflicts — as an example of punishment for ‘bad behavior’ for other nations wanted within the Kremlin’s sphere of influence. Then, Russia’s winning could have been estimated as 4*0+5*7=35.

The crux of the chain-store paradox envisages that the monopolist’s rational choice will be the induction theory approach (the collaborative one). Still, it has the potential to gain more in the case of using the deterrence theory approach. This, however, is considered an irrational decision because it includes a risk of 0 payoffs and involves more variables and decision-making points for other actors’ behavior. In the end, Russia made an irrational decision, opting for an aggressive strategy. Nevertheless, such an approach could only slow Ukraine’s development but not erase its pro-liberal spirit. Therefore, the chain-store paradox proves that Russia’s behavior can and should be considered irrational in the first place, even before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and very much so for the time being. The Russians could not have won Ukraine by their pathetic coercive strategy, their aggression could have not prevented states from seeking security with reliable alliances, but vice versa, speeding up the processes of getting away from the Russian influence.

Conclusion

Given the retrospective overview of the Kremlin’s actions, we can conclude that even though the measures undertaken by the Russians turned out to be highly irrational and destructive at the strategic level regarding long-lasting gains and successful foreign and domestic policy, the Western countries could not succeed in cracking the Kremlin’s plans as they were mainly projecting their own values, mindset, and beliefs to Russia. The full-scale invasion of Ukraine proves that any musings regarding rationality (real or perceived) in Russia’s behavior since 2014 are heading over to the same place as international law conventions – to the dump of history. These musings have been not only buried under the ruins of civilian infrastructure in Ukrainian cities but also drowned in the blood of killed civilians in Bucha, Irpin, Kramatorsk, and Hostomel. The sheer losses from the Russian side, its obnoxious violation of international law, and numerous war crimes pose a severe threat not only to the regional chessboard but to the current world order, which barely can be called ‘rules-based’ anymore.

The only remedy to this highly charged situation can be found in unlocking the military supplies to Ukraine, first and foremost – fighter jets. Ukraine’s victory is only a matter of time but it should not be perceived as a given; the Ukrainians are paying the steepest cost with their lives for every inch of their liberated land and they deserve to get everything to defeat the aggressor. As it has been shown throughout the article, Russia will not give up on its imperialist ambitions whatever it takes; the Kremlin has already opted for the “deterrence strategy” and taking into consideration its recent rhetoric it has no will to play it back.