7 MB

8 MB

Key Takeaways

- The SAFE instrument provides €150 billion in EU loans to support common defence procurement and strengthen the EU’s defence industrial base by reducing fragmentation and improving interoperability.

- However, its capacity to tackle national protectionism is limited, particularly since individual countries can apply for SAFE loans until May 2026. As of September 2025, 19 countries have expressed interest in applying for the full €150 billion available under SAFE.

- While Ukraine is not eligible to receive loans from the EU under the SAFE mechanism, Ukrainian companies can participate in common procurement as (sub)contractors. Together with other EU Member States and EEA/EFTA countries, Ukrainian components shall constitute 65% of the end product. Yet, Ukraine’s defence export ban and its procurement rules, which differ from those of the EU, might significantly impede the process.

- To facilitate Ukraine’s participation in SAFE, Member States should outline Ukraine’s involvement in their European Defence Industry Investment Plans, which are to be submitted to the Commission by November 30, 2025. Thus, SAFE’s effectiveness and Ukraine’s participation will depend primarily on the EU Member States, with the Commission playing a minor role.

- SAFE is a temporary emergency tool and should not be seen as a sustainable long-term solution for European security and defence. A more permanent, centralised funding mechanism should be considered, along with the harmonization of Member States’ export and procurement rules.

Introduction

In 2025, the European Union came under mounting pressure to overhaul its defence posture in response to Russia’s continued aggression against Ukraine and growing doubts about American security guarantees under the ‘America First’ agenda of the second Trump administration. The war has also exposed deep fragmentation in Europe’s defence, including limited weapons interoperability, duplication of procurement efforts, and vast disparities in defence budgets and industrial capacities among Member States.

Recognizing the strategic imperative to strengthen European deterrence posture and provide sustained support to Ukraine, the EU adopted the SAFE instrument as part of the Rearm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030 in March 2025. Building on two earlier EU initiatives, EDIRPA (common procurement) and ASAP (ammunition ramp-up), SAFE significantly surpasses them in terms of financing scale. However, questions remain about how Member States will utilize this instrument, whether it will achieve its intended impact on the European defence industry, and how Ukraine will benefit from it. This policy brief explores these issues.

1. What is SAFE, and How Does It Work?

The ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030 aims to boost European defense capabilities and industrial base through several financial means, one of which is the Security and Action for Europe (SAFE) Regulation, adopted on May 27, 2025. The core objective of the SAFE mechanism is to incentivize common military procurement between the Member States by allocating up to €150 billion in loans backed by the EU budget.

The instrument aims to lower production costs, reduce fragmentation, and enhance interoperability across the EU in the defence and security field. More broadly, it is designed to make Europe more sovereign and responsible for its own defence. Positively for Kyiv, EEA/EFTA countries and Ukraine can also partially benefit from the SAFE under certain conditions.

The two main objectives of the EU’s new financial instruments, as outlined in the White Paper, are:

- Increasing support for Ukraine through the urgent, short-term procurement of weapons, aimed at replenishing stocks or acquiring certain systems quickly.

- Developing EU defence industries in a collaborative manner through long-term investments, yielding results over time.

Key procurement priorities

In light of the current capability shortfalls across the EU and lessons learned from the battlefield in Ukraine, the European Commission has prioritized the following categories of equipment to be procured under the SAFE funding scheme:

- Category one: ammunition and missiles; artillery systems; small drones (NATO class 1) and related anti-drone systems; critical infrastructure protection; cyber and military mobility.

- Category two: air and missile defence; drones other than small drones (NATO class 2 and 3) and related anti-drone systems; strategic enablers; space assets protection; artificial intelligence and electronic warfare.

Timeline and key steps for participation

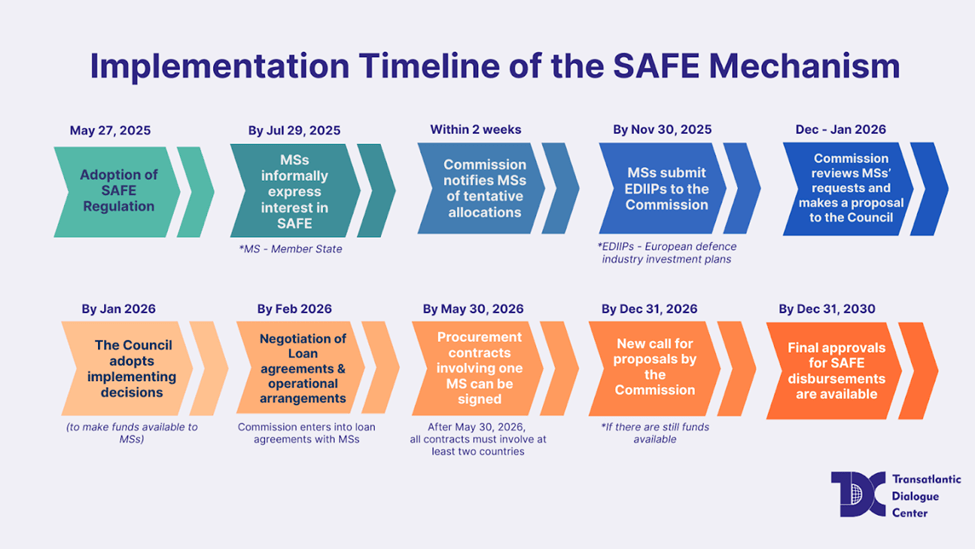

The European Commission has set a timeline for Member States to become funding recipients under the SAFE mechanism:

- Following the enactment of the SAFE Regulation, the Commission launched a call for Member States to express their interest in SAFE and informally indicate the amount of funding they would like to receive by July 29, 2025.

- Within two weeks following the July 29 deadline, the Commission will notify interested Member States about the tentative allocations of the loan amounts available to each of them.

- By November 30, 2025, each interested Member State shall submit to the Commission a financial assistance request together with a European Defence Industry Investment Plan (EDIIP) that comprises the following elements:

- A description of the defence products to be procured using the SAFE funding

- A description of planned activities and expenditure

- If applicable, a description of Ukraine’s involvement in the planned measures

- A description of the planned measures aimed at ensuring compliance with procurement rules

- Following the review and confirmation that a Member State’s plan meets the eligibility criteria, the European Commission will submit a proposal for a Council implementing decision to make the financial assistance available. Within four weeks (by January 2026), the Council shall adopt the implementing decision.

- By February 2026, negotiation of Loan agreements and operational arrangements, triggering pre-financing will be completed. Subsequently, the Commission will enter into aloan agreement with the requesting Member State.

- Procurements carried out by one Member State are eligible for support where a procurement contract was signed by May 30, 2026.

- Contracts signed after May 30, 2026, must include at least two participating countries.

- Should amounts remain available for the financial assistance under the SAFE instrument, the Commission may publish a new call for expression of interest by 31 December 2026.

- Any implementing decisions following the second wave of appropriations may be adopted until 30 June 2027.

- Final approvals for SAFE disbursements to the Member States will be available until 31 December 2030.

Participation requirements and specific conditions

To ensure the effectiveness of the SAFE mechanism, the European Commission has established several key requirements that funding recipients shall comply with.

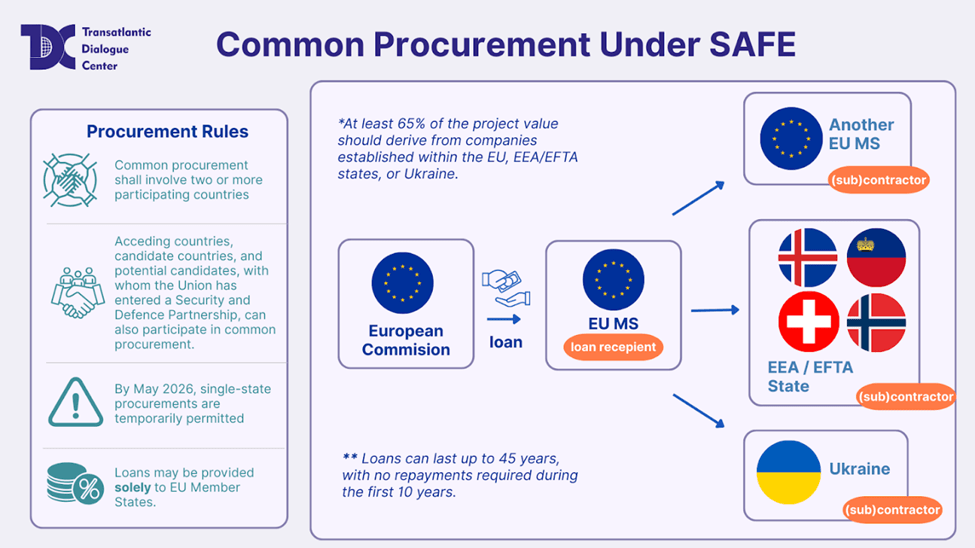

1. Common procurement

Projects should normally involve at least two participants (e.g., two Member States, a Member State and an EEA/EFTA state or Ukraine, or a Member State and other third countries*). As a deviation from the rule, single-state procurements are temporarily permitted during an initial phase.

2. “Buy European” rule

At least 65% of the project value should derive from companies established within the EU, EEA/EFTA states, or Ukraine. A maximum of 35% of the estimated cost of the end-product’s components may come from external suppliers or subcontractors from third countries (e.g., the U.S.).

3. Loan access

Loans are available on highly favorable terms: they can last up to 45 years, with no repayments required during the first 10 years. Additionally, up to 15% of the funds may be disbursed in advance to help projects get started.

Noteworthy, loans may be provided solely to EU Member States. If a third country, such as Ukraine, participates in common procurement, the funds will be disbursed to the Member State involved. Based on its European Defence Industry Investment Plan, the respective Member State will allocate the funding among the approved activities.

2. SAFE critical analysis and potential outcomes for the EU

The SAFE instrument is a pragmatic step toward strengthening EU defence capabilities in response to growing geopolitical threats. Its core advantage lies in its aim to promote common procurement, intended to foster greater collaboration among Member States’ industries and reduce fragmentation in the EU defence market. By mandating that 65% of spending be directed toward EU-based production, SAFE seeks to strengthen Europe’s defense industrial base, while also embracing a holistic European—rather than strictly EU-exclusive—approach by enabling participation from third countries such as Ukraine, EEA/EFTA members, and acceding, candidate, and potential candidate countries.

Despite the EU’s ambitious goals under SAFE, its overall scale is still modest. While Commission officials note that SAFE’s size (€150 billion) accounts for over half of the EU member states’ annual defence spending, this figure appears modest relative to its objectives. Reducing reliance on the United States—as envisioned in the SAFE Regulation—would, according to some estimates, require close to $1 trillion. For decades, the EU has depended heavily on the US for airlift, satellite communications, and aerial refueling, with 78% of European defence procurement in 2022–2023 spent on non-European products. SAFE alone cannot cover these expenses and has several limitations that remain unresolved.

Since SAFE is designed to rapidly address critical capability gaps, it functions as a credit facility that may not appeal to all countries. Firstly, loans count toward the national debt, and Member States with limited fiscal headroom may struggle to use SAFE effectively. In simple terms, fiscal space refers to a government’s capacity to take on additional debt without jeopardising financial stability.

Not all EU countries are equally positioned in this regard: those with higher debt levels have less fiscal space, and vice versa. France, for instance, currently carries one of the largest budget deficits (-5,8%) in the EU and a pretty high budget debt (around 113%) but aims to raise defence spending to 3–3.5% of GDP. As of July 2025, France has expressed interest in SAFE loans, though likely for a modest sum.

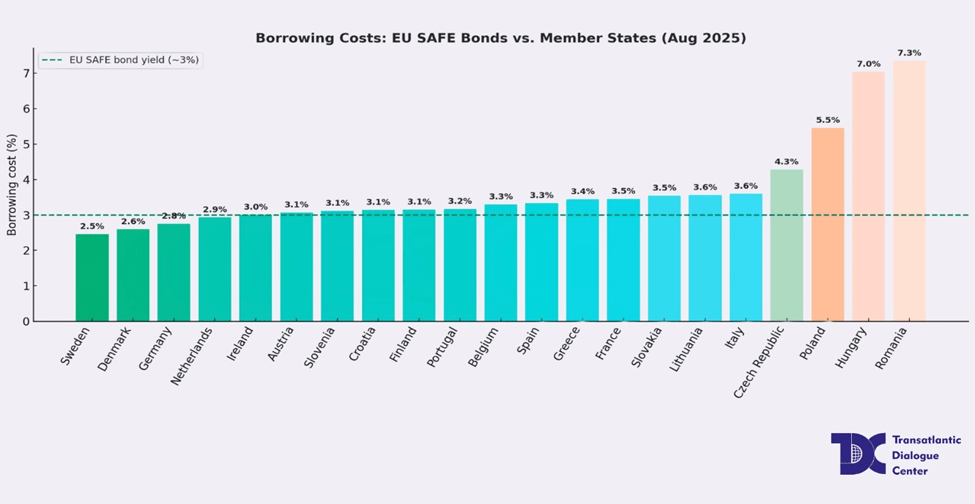

Additionally, borrowing at the EU’s interest rates is not attractive for all Member States. SAFE essentially allows the EU to raise up to €150 billion on stock markets and re-loan it to Member States at comparatively low interest rates. With EU bond yields around 3%, SAFE loans are expected to carry a similar rate. This presents a significant advantage for countries with higher borrowing costs—such as Romania (7%), Poland (5.4%), and the Czech Republic (4.3%)—which stand to benefit from accessing cheaper EU-level financing.

However, for many Member States, the gap between EU and national borrowing costs is relatively small. Wealthier countries with strong (AAA) credit ratings—like Germany (2.6%), the Netherlands (2.8%), Sweden (2.4%), and Denmark (2.5%)—have little incentive to use SAFE, as their own borrowing costs are lower than the EU’s. Yet, surprises are possible – for instance, Denmark back in July, has openly stated it does not plan to use SAFE loans, preferring to finance its defence investments independently. In September, however, it became the last EU member state to express interest in receiving SAFE loans. Reportedly, the possibility to support Ukraine via SAFE pushed the country towards this decision.

As of September 1, 2025, nineteen EU Member States had expressed interest in taking out loans worth at all €150billion. These include Belgium, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Finland and Denmark.

While some Member States appear genuinely committed to strengthening their defence posture—Poland, for example, has assembled projects worth approximately €45 billion—others may use SAFE more symbolically, signaling support for the EU’s defence objectives without substantial engagement. Italy, for instance, has expressed interest in €14 billion, while Greece is seeking €1.27 billion. The final funding requests and detailed European Defence Industry Investment Plans are expected in November, but how countries choose to spend the funds—collaboratively or independently—may matter more than how much will be spent.

The EU defence market remains highly fragmented, with procurement typically conducted at the national level and often favouring domestic industries. This leads to missed opportunities for synergies and economies of scale, further exacerbated by excessive platform diversity across Member States and the absence of harmonized export regulations across the EU.

SAFE’s goals—common procurement, reduced market fragmentation, and improved interoperability—can only be met if countries act with unity and political will, rather than compete for funds. Mutual distrust could easily lead to national interests outweighing common initiatives, undermining the programme’s purpose.

In this context, SAFE is unlikely to address national protectionism effectively, despite its collaborative intent. Under current rules, SAFE loans require applications from at least two Member States, but during the first year, until May 2026, individual Member States may also apply independently. Additionally, at the request of some Member States, the Commission has allowed existing defence programmes to be funded under SAFE.

These conditions may not offer sufficient incentives for broad cooperation, and Member States may instead use SAFE primarily to bolster their own industries. This trend is already apparent in the preliminary applications submitted as of July 2025, with Member States reportedly putting forward individual proposals prioritizing domestic industries. For example, Polish officials state that Warsaw will likely use the funding to support domestically produced equipment—such as drones and counter-drone systems under the “Eastern Shield” initiative, artillery ammunition, Krab self-propelled howitzers, Rosomak vehicles, and Jelcz logistics trucks.

If most of the 19 applicant countries submitted individual proposals, they would nearly exhaust SAFE, turning a tool intended for common procurement into one for individual financing.

In this way, SAFE risks failing to achieve its goal of promoting common procurement and reducing fragmentation in the EU defence market. This risk could still be mitigated by the Commission, which takes the final decision on fund allocation; however, both the criteria for these decisions and the specific body within the Commission responsible, along with its expertise, remain unclear.

Given the above, SAFE should not be considered a sustainable long-term solution for European security. The very regulation establishing SAFE defines it as a temporary, ad hoc instrument, complementary to existing EU initiatives like the European Defence Fund (EDF). It is not the first time the EU has used Article 122 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) to offer emergency financial assistance. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU launched the SURE instrument under the same legal basis to support employment.

However, the defense and security sector differs fundamentally from areas like unemployment: defense spending cannot be treated as a temporary deviation from fiscal norms. This makes the short-term nature of SAFE its core limitation. For defense firms on both sides of the Atlantic, the main barrier to scaling up production is not a lack of funding per se, but rather the absence of predictable, long-term government orders. Defense requires consistent, long-term investment rather than one-off emergency funding.

To build on SAFE’s foundations and address its limitations, the EU will need to adopt more permanent, centralised funding mechanisms to ensure lasting strategic autonomy. One example is the proposed European Defence Mechanism (EDM), an intergovernmental body that would centralise European defence procurement and capabilities, while enforcing cooperation through shared funding and binding rules.

A coordinated strategy with a substantial budget (e.g., €500 billion over five years) may be the only way to tackle the persistent fragmentation of the EU defence market. The Commission’s proposal to allocate €131 billion for defence in the next Multinational Financial Framework is unlikely to address this issue.

So far, for SAFE to achieve its intended impact, Member States should take a proactive role. The EU has created a strong and promising financial instrument, but its success ultimately depends on how effectively and ambitiously Member States choose to implement it.

3. Ukraine’s Role in SAFE

Key provisions for Ukraine’s participation as a third country

It is often stated that Ukraine can participate in SAFE on an equal footing with EU member states and benefit greatly from the process. This, however, is only partially true.

The novelty of the SAFE mechanism lies in the fact that Ukraine’s arms producers and tech companies can participate in common procurement as (sub)contractors, along with EU-based companies, receiving funding from the loan acquired by an EU Member State.

65% of components of the end product should originate from either EU Member States, EEA/EFTA countries and or Ukraine. In this sense, Ukraine can indeed be considered part of Europe. In contrast, acceding, potential candidate, and other EU candidate countries (referred to in the SAFE Regulation as “other third countries”) can also participate in SAFE as subcontractors, but under much stricter conditions. Their contributions are considered to originate from “outside the Union” and can only constitute up to 35% of the end product.

Ukraine’s territory can also be used for manufacturing purposes, as according to the SAFE Regulation,

“the infrastructure, facilities, assets, and resources of the contractors and subcontractors involved in the common procurement that are used for the purposes of the common procurement shall be located in the territory of a Member State, an EEA EFTA State, or Ukraine”.

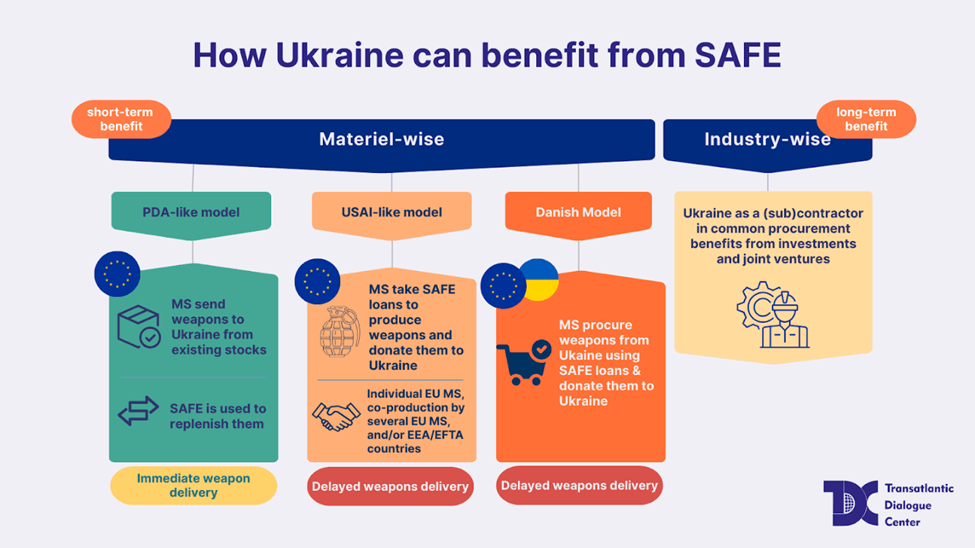

How Ukraine can benefit from SAFE

- Materiel-wise (short-term benefit). Ukraine can benefit as a recipient of military equipment, as well as logistics, reconnaissance etc.

- Member States would be donating to Ukraine weapons from their existing stocks, and SAFE would be used to replenish them (approach similar to American PDA)

- Member States would be donating to Ukraine weapons procured with the help of SAFE loans from:

- Individual EU member states, co-production by several EU Member States, and/or EEA/EFTA countries (approach similar to American USAI);

- Ukraine or joint Ukrainian-EU ventures (approach similar to the “Danish model”).

- Industry-wise (long-term benefit). Ukraine can benefit as a (sub)contractor in common military procurement from investments and joint ventures.

Models for Ukraine’s Participation In Detail: Opportunities and Challenges

- Ukraine as a Recipient of Military Equipment

One of the ways for Ukraine to benefit from the SAFE mechanism is through being designated as a recipient of equipment delivered as military aid. The SAFE Regulation contains a separate clause encouraging Member States to include, where relevant, a description of Ukraine’s anticipated involvement in their planned activities in their European Defence Industry Investment Plans. In a recent resolution, the European Parliament included a clause encouraging Member States to devote a significant part of their European Defence Industry Investment Plans to assistance for Ukraine. Several scenarios appear feasible within the framework of the SAFE provisions:

- Ukraine as a recipient of military equipment donated by Member States from their existing stocks, with SAFE loans used to replenish them.

Ideally, beyond promoting common procurement, the SAFE financial instrument was also intended to encourage Member States to increase military support for Ukraine. The underlying idea is to provide financial support for EU Member States to procure new military equipment for themselves, thereby enabling them to provide equipment from existing stocks to Ukraine. This would deliver prompt results for Ukraine while ensuring that Member States receive guaranteed replenishment (a mechanism similar to the American Presidential Drawdown Authority (PDA)). However, much will depend on the political decisions and national priorities of each Member State, as well as the pace of SAFE implementation.

- Ukraine as a recipient of military equipment procured from individual EU Member States, co-production by several EU member states, and/or EEA/EFTA using SAFE loans.

Similar to the previous scheme, Ukraine may be designated as a potential recipient of military equipment procured by the Member States under the SAFE financial instrument. However, such a scenario would delay support for Ukraine, as procurement procedures and the establishment of new production lines would take time (a mechanism similar to the American Ukraine Security Assistance Initiative (USAI)).

The key problem lies in the incentives for the Member States to donate the newly produced equipment to Ukraine, instead of replenishing their own stocks. As a way out, Ukraine can engage with Member States that have previously provided essential equipment and which Ukraine still requires to encourage them to supply additional units of the same systems, this time financed through the SAFE financial instrument.

- Ukraine as a recipient of military equipment procured from Ukraine or joint Ukrainian-EU ventures using SAFE loans.

Within this scenario, Ukraine will benefit from the local manufacturing of defence equipment in cooperation with EU companies operating on Ukrainian territory. This approach is similar to elements of the “Danish model,” which allows interested countries to finance Ukraine’s defence industry and donate the produced equipment back to Ukraine. Spearheaded by Denmark, the “Danish model” has become the first mechanism to involve direct procurement from Ukrainian defence manufacturers. This model could serve as a blueprint for SAFE-funded procurement, involving Ukrainian defence and technology companies and their facilities in Ukraine.

Under SAFE, however, the key distinction lies in the mandatory participation of EU Member States as loan recipients. Technically, an EU Member State can disburse the funding to a European company, which will produce together with a Ukrainian company using the latter’s facilities on Ukrainian territory. Alternatively, an EU Member State receiving a loan could procure weapons from a Ukrainian company, acting as a single contractor, and donate them back to Ukraine. In this case, Ukraine’s export ban would not apply.

In short term, SAFE funding would combine rapid procurement with solutions proven effective in war for Ukraine’s current needs. Since many Ukrainian industries source components from EU, investments would also benefit the European industry, allowing partners to select trusted Ukrainian contractors and ensure supply chain security.

Joint Ventures with Ukrainian Companies: A Contractor Model

In the long run, with Ukraine designated as a (sub)contractor to the EU member state receiving the SAFE loan, not only would the Ukrainian army benefit from SAFE as a recipient of equipment, but also Ukrainian industries would benefit as beneficiaries of long-term investments and joint ventures with European partners.

The Ukrainian defence industry is among the most rapidly developing and expanding in the world. Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine has increased its production capacity thirty-fivefold: from $1 billion in 2022 to $35 billion in 2025. However, in 2024, Ukraine only managed to secure around $10 billion in funding. SAFE-funded investments could further unlock the potential of Ukrainian industries by expanding their production lines, accelerating delivery schedules, and scaling up innovative projects already tested in combat.

Additionally, allowing Ukrainian companies to participate in joint ventures represents a positive shift in mindset, granting the Ukrainian defence industry at least partial access to collaboration with European companies. This is an important step toward broader integration of Ukraine’s arms producers into the European defence ecosystem, helping to promote standardization, interoperability, and improve cost-efficiency. As of late 2024, Ukraine has established five joint ventures with Western arms manufacturers, including companies from Germany and Lithuania. In addition, European companies, such as Germany’s Rheinmetall, began constructing production facilities in Ukraine, while the UK’s BAE Systems is partnering with local firms to service and maintain its equipment. The Franco-German manufacturer KNDS plans similar cooperation, and the Czechoslovak Group is setting up ammunition plants in the country. SAFE could provide another important push in this direction.

Key challenges for Ukraine

Questions remain about Ukraine’s real opportunities for participation. Despite the SAFE’s proclaimed objective of establishing an additional mechanism to enhance support for Ukraine, its key provisions and participation conditions suggest that Ukraine’s potential benefits may be narrow in scope.

One of the main concerns is whether the EU Member States would actually be willing to include Ukraine in their European Defence Industry Investment Plans. Given that Ukraine can only participate as one of the (sub)contractors, Member States may tend to focus on boosting their domestic defense producers’ capabilities. Furthermore, trust issues and the lack of common priorities may prevent interested countries from planning joint projects with Ukraine, as it may be more time-consuming and require additional due diligence processes.

The Commission, in turn, also has very limited tools at its disposal to influence the decisions of Member States. At the same time, Ukraine risks missing the opportunity to derive real benefits from this financial instrument due to the short timeframe for submitting Member States’ European Defence Industry Investment Plans.

There are also challenges on Ukraine’s side. While the SAFE Regulation allows its territory to be used for co-production, this conflicts with the export ban Ukraine has enacted since the 2022 invasion. According to Ukrainian legislation, specifically the Law “On State Control over International Transfers of Military and Dual-Use Goods”, the export of defence items is generally prohibited and may only occur with proper authorization from the designated state authorities.

Therefore, technically, any equipment manufactured in Ukraine using SAFE funding should remain for end-use within the country, unless the government lifts the export ban.

However, this does not apply to Ukrainian companies that are registered in the EU Member States and own manufacturing facilities there.

In addition, legal barriers related to third-country control and intellectual property restrictions in Ukraine may create additional obstacles for Ukraine’s engagement in common procurement. In parallel, Ukraine’s expanding network of R&D accelerators, innovation hubs, and associations lacks sufficiently robust intellectual property (IP) protection mechanisms. Ensuring robust IP protection protocols would foster investor confidence, enable secure technology transfer, and facilitate Ukrainian participation in European and global defense initiatives.

Such a framework suggests that there is no guarantee that Ukraine will be systematically included in planned investments. Without strong incentives or coordination tools to prioritize Ukraine’s involvement, there is a risk that Member States will pursue purely national agendas, sidelining collaboration with Ukrainian defense industry actors.

4. Ukraine’s priorities and proposals for SAFE funding

In May-June 2025, the Ukrainian Ministry of Defence outlined Ukraine’s priorities for the SAFE funding and what the country can offer to the EU. Ukraine is particularly interested in common procurement and production of the following categories of equipment:

- UAVs: Ukraine’s capabilities, including FPV and sea drones, ground robotic systems (GRS), are of particular interest to the EU, as Ukrainian drone producers are highly adaptable and can adjust the technology and their equipment’s functional specifications rapidly. Among the capabilities that Ukraine could offer to the EU are domestically developed strike UAVs, like the An-196 “Lyutyy” and drone missiles “Peklo”. These long-range weapons, already proven in combat, exemplify cutting-edge innovations shaped by modern warfare. EU Member States may be particularly interested in integrating Ukraine’s innovative drone solutions into their air defence strategies.

- Ammunition: In 2022, Ukraine had no domestic production of 155mm shells. Today, in cooperation with international partners, Ukraine is building the capacity to manufacture over 1 million shells annually.

- Missile systems: While Ukraine remains highly reliant on the Western strike systems, it has also been developing its own, more cost-effective capabilities. Ukraine will likely offer common procurement of its recently developed Neptune cruise missile, a long-range ship weapon, and the Sapsan ballistic missile.

- Air defence: Given the continuous need for air defence systems and ammunition, Ukraine hopes to be included in the defense industry investment plans of EU Member States owning key European air defence capabilities. These countries include France and Italy, producers of SAMP-T systems.

- Artillery systems: The 155mm SPH Bohdana is Ukraine’s first domestically designed NATO-caliber howitzer, proven in combat. Its lower cost and wheeled design offer a flexible, affordable option that could interest European countries seeking modern, easily maintainable artillery systems. Bohdana systems could potentially be funded through SAFE, providing an opportunity to scale local production in Ukraine and collaborate with European producers. At the same time, Ukraine may be interested in joint projects with European producers of artillery systems, which have previously been supplied to Ukraine. Examples include but are not limited to France (Nexter / CAESAR), Poland (Huta Stalowa Wola / Krab), and the Czech Republic (Czechoslovak Group).

- Electronic warfare (EW): Through intense combat, Ukraine has developed and tested EW systems that detect, jam, and neutralize enemy drones, disrupt command networks, and protect friendly forces. Unlike many European armies, Ukraine’s solutions are continuously adapted to a dynamic adversary changing frequencies and tactics daily.

Ukraine is particularly interested in common procurement with the Nordic countries and Germany, which have both capabilities and interest in supporting Ukraine. However, SAFE loans offer unattractive interest rates for these countries. Despite this, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and Germany – each with strong economies – have recently pledged $1.5 billion to purchase U.S.-made weapons for Ukraine through the NATO Prioritised Ukraine Requirements List (PURL) initiative. Ukraine has also flagged its interest in working with key European suppliers of air defence systems and ammunition, such as France and Italy.

Reportedly, countries including Portugal, Spain, France, Bulgaria, and Slovakia may be interested in involving Ukraine in their European Defense Industry Investment Plans. Among the Member States interested in accessing SAFE loans, there is strong enthusiasm for collaboration with Ukraine in UAV development, deployment, and technology sharing. Croatia and Latvia have already discussed allocating SAFE funding for Ukraine’s needs with President Zelenskyy and former Prime Minister Shmyhal.

Case studies: potential use of SAFE loans

The following case studies outline possible scenarios where SAFE loans could be used to support joint EU–Ukraine defence production.

- Czech Republic & Ukraine: Scaling up ammunition production

Ukraine’s sustained need for ammunition can be used to illustrate how the SAFE procurement model could work in practice.

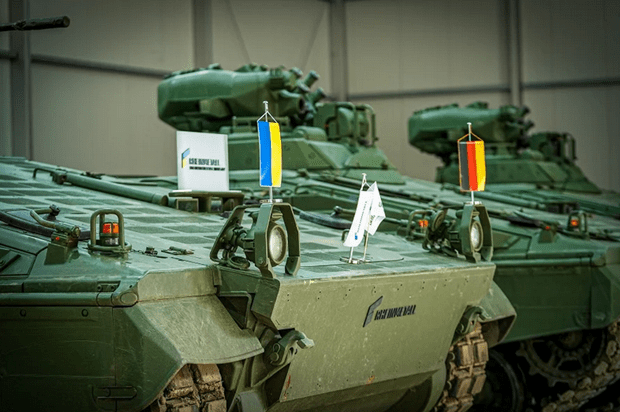

According to the EU’s White Paper, the Union committed to delivering a minimum of two million rounds of large-calibre artillery ammunition annually. The Czech Republic, which has expressed its interest in taking out SAFE loans, has been one of the main suppliers of 155 mm artillery shells to Ukraine. Notably, in October 2024, Czechoslovak Group (CSG) announced the conclusion of an agreement with Ukrainian arms artillery ammunition locally in Ukraine. According to the CSG’s press release, CSG and Ukrainska Bronetechnika will produce 100,000 artillery shells in 2025, with output rising to over 300,000 annually from 2026. Production in both the Czech Republic and Ukraine aims to boost supply for the Ukrainian army and lower costs.

Given that ongoing projects can also receive funding under the SAFE mechanism, the CSG and Ukrainska Bronetechnika can potentially request SAFE funding to expand their manufacturing capabilities in Ukraine, further reduce costs, and provide Ukraine with vitally important equipment. In this case, Ukrainska Bronetechnika could act as a subcontractor, whose Ukraine-based facilities will be used for localised production with further supplies to the Armed Forces of Ukraine.

2. Estonia and Ukraine: SAFE funding potential of the European-Ukrainian USHORAD alliance

In May 2025, Ukraine and Estonia formed the Air Defence Tech Alliance for Ukraine, aiming to

“close critical capability gaps on ultra-short-range air defence (USHORAD) and establish a European-Ukrainian defence industrial partnership capable of rapid innovation and scalable production. ”

Under this cooperation framework, DefSecIntel Solutions (Estonia), Ukrainian defence industry partners (Gauss Glide, Drone space labs, LLC Proinvest, Vk Systems, EW Spectrum), and Weibel Scientific (Denmark) have agreed on integrating Weibel’s radar technology with DefSecIntel’s ultra-short-range air defence (USHORAD) systems and Ukrainian interception effectors into fully automated, scalable defence platforms. Such an initiative represents a step towards developing joint solutions to meet Ukraine’s current need for anti-drone systems and support broader European initiatives, such as the Baltic Drone Wall.

Assessing the eligibility criteria, this project meets a key requirement of the SAFE mechanism. It represents a potential flagship model for cross-border EU–Ukraine defence cooperation with direct battlefield relevance and scalable industrial benefits for Europe’s own security needs. As such, it represents a strong candidate for potential funding under SAFE.

5. Recommendations

For the EU Member States:

- Include Ukraine in Member States’ European Defence Industry Investment Plans. Seek Ukrainian companies’ involvement to benefit from battlefield testing. Ukraine has served as a testbed for various Western systems, enabling producers to adapt their technologies to evolving modern warfare and develop more effective solutions.

- Prioritize projects with dual benefit – those that both strengthen the EU defence base and contribute directly to Ukraine’s current defence needs. As Ukraine faces shortages in air defense ammunition, prioritize accelerating its production. As Ukraine seeks to develop anti-drone solutions and scale up drone interceptor production, encourage common procurement focused on these solutions. Consider Ukraine’s role as a potential R&D and manufacturing partner – not just a recipient of procured equipment.

- Use other creative ways to ensure Ukraine’s benefit from SAFE: deliver a portion of existing stocks to Ukraine and use SAFE loans to replenish it (similar to American PDA) or donate a portion of jointly procured equipment under SAFE to Ukraine (similar to American USAI) to support its defence and resilience and contribute to degrading Russia’s military capabilities.

- Harmonise defence export regulations to enable effective cross-border defence cooperation and integrate trusted partners like Ukraine. Despite a common legal framework, Member States apply export controls differently, causing delays, legal uncertainty, and inefficiencies. Aligning licensing procedures, classifications, and enforcement would streamline common procurement and boost industrial collaboration.

For Ukraine:

- Identify potential partnerships between Ukrainian arms producers and their European counterparts across interested EU Member States based on the domestic defence industry capabilities. Encourage Ukrainian defence companies to prepare technical dossiers and proposals to potential partners across the EU.

- Engage with potential loan recipients among EU Member States and advocate for the inclusion of Ukrainian companies in their European Defence Industry Investment Plans (EDIIPs). Support Ukrainian stakeholders, including industry associations and defense advocacy groups, in actively engaging with the European Commission during its assessment of Member States’ EDIIPs to ensure Ukraine’s interests are reflected.

- Appoint a dedicated body or task force to manage SAFE engagement and liaise with EU institutions, national governments, and industries. This body would act as a counterpart to the EU-Ukraine Task Force on Defence Industrial Cooperation, which manages Ukraine’s participation in SAFE on the EU side.

- Assess the feasibility of lifting or selectively easing export restrictions to enable co-production, exports, and greater integration of Ukrainian firms into European defense procurement. Work toward aligning the defence export control system with EU standards to enable smoother defence industrial cooperation.

- Ensure legal and operational alignment with EU procurement procedures to avoid delays.

- Continue strengthening Ukraine’s legal and institutional framework for the protection of intellectual property (IP), especially in the defense and high-tech sectors, to prevent misappropriation of domestically developed innovations. Provide dedicated legal advisory support to manufacturers engaged in international cooperation to mitigate the risk of technology theft and safeguard proprietary know-how.