2 MB

Key Takeaways

- Russia is a major, escalating global security threat with growing military ties to rogue states and economic support from China, showing no interest in genuine peace despite sanctions.

- Sanctions are a crucial tool to weaken Russia’s military, but their impact is limited by Russia’s economic adaptation via war spending and effective evasion tactics.

- Russia circumvents sanctions through parallel trade via third countries (Central Asia, Turkey, India, China) and a “shadow fleet” for oil exports, often utilizing Western-origin components in its weaponry.

- Current sanctions enforcement has loopholes, requiring a more robust and coordinated strategy to close them and truly impact Russia’s war-funding capabilities.

- A smarter sanctions approach necessitates targeting facilitators of evasion (shipowners, transshipment hubs, defense industry links, enablers in third countries), further restricting Russian finance and energy, and ensuring strict enforcement with significant penalties.

- Sustained sanctions pressure is vital long-term, even post-conflict, to counter Russia’s enduring threat and war-driven economy.

Contemporary Russia is the main threat not only to Ukraine but to global security. It legitimizes unpunished aggression, undermines established international law norms, and strengthens the axis of autocracies that have been isolated by sanctions. At least 70% of Russian artillery is now supplied by North Korea, along with a portion of ballistic missiles and military personnel. Iran systematically provides attack drones, Belarus offers its territory, while China ensures Russia’s economic stability by assisting in circumventing Western sanctions and expanding military-technological cooperation.

From the very beginning of its unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, Russia has engaged in systematic nuclear blackmail against Western countries. The latest example came in November 2024, when Moscow threatened to use the intercontinental missile “Oreshnik” against the UK, Germany, and others. At the same time, the Kremlin demonstrates zero interest in peace negotiations or compromise. Even against the backdrop of Donald Trump’s peace proposals, Russia has not changed its rhetoric, continues to put forward demands equivalent to capitulation, and has not decreased the intensity of hostilities on the battlefield.

In 2025, military spending reached a record-high 33% of the yearly budget, a clear indication of military capacity building instead of preparation for peace. According to the Danish Defence Intelligence Service, Russia is preparing for war with NATO and could become an existential threat to Europe within the next five years.

The Role of Sanctions in the War

Therefore, if Russia’s “special military operation” in Ukraine succeeds, a direct clash with NATO will become highly likely. In fact, discussions and preparations for a potential Russian invasion of the Baltic states and Poland are already taking place within the alliance. Countries in the region have been actively preparing for this scenario—strengthening national borders, stockpiling weapons, increasing military spending to 3% of GDP, enhancing air defense systems, and even presenting civilian evacuation plans.

Obviously, sanctions are not the primary tool to stop Russian aggression, yet they play a crucial role in weakening Russia’s military potential—something that is critical both for the outcome of the war in Ukraine and for preventing a future war in Europe. Sanctions gradually complicate Russia’s ability to wage war, making it more exhausting and reducing the appeal of cooperation with the Kremlin for third countries. By restricting financial flows and access to critical technologies, they increase strategic pressure and force Russia to pay a higher price for continuing the war.

Sanctions Imposed by the G7

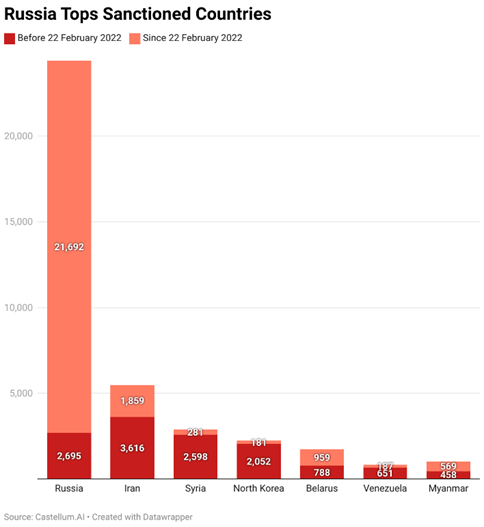

Today, the Russian Federation is the absolute world leader among sanctioned states, surpassing Iran, which holds second place, by 323.4% (see image). Although some sanctions had already been imposed before the full-scale invasion in response to the occupation of Donbas and Crimea, the majority were introduced starting in 2022. The first measures following February 24 targeted Russia’s financial system: the EU, the US, the UK, Canada, and other partners froze the assets of Russian banks as well as the gold and foreign currency reserves of the Central Bank, disconnected them from SWIFT, and imposed personal sanctions on top officials and oligarchs—including Lavrov, key figures in the military-industrial complex, and Putin himself.

At the same time, restrictions on the export of technologies essential to the Russian economy—particularly its military sector—were introduced. The US, Japan, and other partners imposed controls on the supply of high-tech equipment, semiconductors, aviation parts, and software. The next step was the introduction of sectoral sanctions, primarily targeting Russia’s energy sector. In 2022, the United States and the United Kingdom were the first to impose a full embargo on Russian oil and gas. Gradually, the EU joined these measures, adopting decisions to restrict Russian oil imports, impose a price cap, and sanction Russian energy companies. By 2023, sanctions had expanded to include restrictions on Russian metals, coal, diamonds, and other strategic resources.

According to Ukraine’s Ministry of Finance, as of February 2024, Russia had lost approximately $400 billion due to sanctions. However, given Russia’s adaptation to the sanctions regime, in 2023-2024, the sanctions coalition shifted its focus to combating sanctions circumvention—introducing secondary sanctions and measures against Russia’s so-called “shadow fleet.”

War Economy: Russia’s Fragile Stability

Despite earlier forecasts predicting an inevitable economic collapse due to sanctions, the Russian economy has demonstrated relative stability. In 2022, GDP declined by only -1.2%, while in 2024, it grew by +3.6%. The IMF projects a 1.4% increase in 2025, raising the question: why haven’t sanctions had a more destructive effect?

A key factor sustaining the economy is massive war-related spending. GDP growth is largely driven by a 60% increase in military production, rather than organic economic expansion. However, this stimulus model has side effects, signaling that the economy is overheating.

First, Russia faces an acute labor shortage caused by a combination of factors: mobilization, the outflow of labor migrants due to sanctions on bank transfers, population emigration, and demographic decline. The unemployment rate has dropped to a record low of 2.6%, the lowest since the Soviet era. This means the labor market is operating at full capacity, forcing businesses to raise wages simply to retain employees. While this artificially stimulates consumer demand, it also fuels inflationary pressure. As of February 2025, inflation has reached 14% and is likely to continue rising due to increased military spending and financial incentives for mobilization—primarily high military service pay.

Meanwhile, the government is actively depleting its reserves. The National Welfare Fund has shrunk from $113.5 billion in 2021 to $55 billion in 2024, signaling a gradual exhaustion of financial buffers.

Dependence on energy exports remains a critical weakness. Despite sanctions, Russia continues selling oil through alternative supply channels. However, its economic stability remains highly vulnerable to fluctuations in global oil and gas prices. A sharp drop in prices or stricter sanctions enforcement could significantly constrain its ability to finance the war.

Sanctions Evasion Schemes

Sanctions were expected to restrict Russia’s access to critical goods and technologies for its military-industrial complex while also undermining its economic stability. However, the Kremlin has developed effective mechanisms to circumvent export and import restrictions, allowing it to continue manufacturing weapons, sustaining the war effort, and keeping the economy afloat.

The key methods of sanctions evasion are “parallel trade” through third countries and reorientation to alternative markets. Notably, even G7 countries are indirectly involved in these schemes to some extent.

Parallel trade refers to a mechanism where sanctioned goods are first shipped to intermediary countries and then rerouted to Russia. Central Asian states play a leading role as transit hubs—Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, Uzbekistan, Georgia—as well as Turkey, India, and China. For instance, Russian entrepreneurs make deals with Armenian partners, who in turn order electronics from Germany and ship them to Russia. At the same time, Russian goods are exported to Armenia, where they are later sold on the European market under false labels. A telling indicator is that German exports to Armenia surged from $0.5 million to $4–6 million per month, strongly suggesting that a significant portion of these goods is being re-exported to Russia.

The sharp increase in trade between the G7 and intermediary countries confirms the scale of sanctions circumvention. While the exact volume of these “underground” flows is difficult to estimate, the case of Kazakhstan is particularly revealing. In 2023, compared to 2021, Kazakhstan’s total exports increased by €24 billion and imports by €15 billion—without any significant structural changes in trade or growth in citizens’ incomes. EU imports from Kazakhstan alone rose from €17 billion in 2021 to €30 billion in 2023, strongly indicating its role as a transit hub for re-exports to Russia.

Similar trade patterns are observed across other countries:

- Imports to Kazakhstan from Italy, France, and Japan increased by 60–94%.

- Imports to Uzbekistan from Lithuania and Belgium surged by 79–119%.

- Kyrgyzstan received several times more goods from Poland, the UK, and Finland than in previous years.

- Armenia recorded abnormal trade growth with the EU, with exports from Lithuania increasing fivefold and from the Czech Republic and Estonia by a staggering 16 times.

At the same time, Russia’s trade reorientation toward non-sanctioning countries significantly weakens the effectiveness of Western pressure. While exports from sanctioning countries to Russia dropped from $10.5 billion per month to $4.6 billion in 2023, Moscow has partially offset these losses by increasing trade with countries that have not joined the sanctions. Exports from China, India, Turkey, and Kazakhstan to Russia rose from $5.5 billion per month to $9.7 billion.

Western Tech in Russian Weapons

A critical challenge is not just sanctions violations but the fact that Western components continue to be used in Russian military equipment. Among the wreckage of Russian weapons in Ukraine, nearly 2,800 foreign components have been identified—around 95% of them produced by companies headquartered in sanctioning coalition countries.

Russia relies on third countries to procure critical military and dual-use technologies. For example, 75% of American microchips reach Russia through Hong Kong and China. In 2023, the EU exported over $14 billion worth of microchips, manufacturing equipment, and dual-use goods to countries involved in re-export schemes. This has allowed Russia to maintain and repair its aviation fleet—in 2022 alone, it imported $14 million worth of American-made aircraft parts via China and Turkey.

Money for the War

Financing the war against Ukraine remains Russia’s top priority, as evidenced by its record-high military spending. According to the approved 2025 budget, $126 billion has been allocated to the military—the highest amount since the Soviet era. This accounts for 32.5% of the entire budget (a 25% increase from 2024) and exceeds the combined expenditures on education, healthcare, social policy, and the national economy. Moreover, according to expert Craig Kennedy, an additional $87 billion is funneled through shadow financial operations annually, bringing total estimated military spending for 2025 to approximately $232 billion.

The main source of revenue for Russia’s budget is the sale of natural resources, particularly oil, gas, and coal, which traditionally account for 40–50% of state income. Since the start of the full-scale invasion, Russia has earned over €816 billion from energy exports—68% from oil, 21% from gas, and 11% from coal. In 2025, oil and gas revenues are expected to make up 5% of GDP, while war expenditures will reach 6.31% of GDP—a forecast based on an average oil price of $70 per barrel.

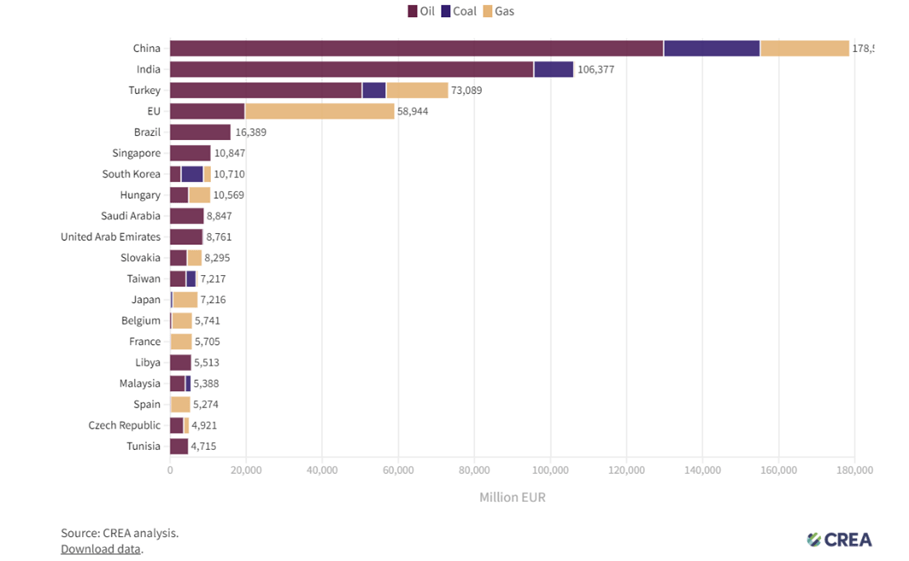

Following EU restrictions, Russia reoriented its energy exports: in 2023, 82% of its exports went to the Asia-Pacific region. China imported €230 billion worth of Russian energy resources, India €122 billion, and Turkey €94 billion.

Largest importers of fossil fuels from Russia From 1 January 2023 until 08 April 2025

Shadow Fleet

One of the key mechanisms for circumventing sanctions on Russian energy exports is the use of the so-called “shadow fleet”—a network of tankers registered in third countries that transport Russian oil at prices exceeding the Western-imposed cap.

The most common schemes involve the “gray fleet” and the “dark fleet.” The gray fleet formally operates within the rules but employs questionable methods, such as sailing under foreign flags (Panama, Liberia, the Marshall Islands, Malta). This has allowed Russia to increase oil transport volumes by 111% since the invasion. The dark fleet, on the other hand, completely conceals its operations—ships turn off their Automatic Identification System (AIS), manipulate location data, and use other masking techniques.

Russia began purchasing tankers to bypass sanctions immediately after the $60-per-barrel price cap was introduced in 2022. Since the start of the full-scale invasion, shipowners from 21 out of the 35 sanctioning countries have sold at least 230 tankers to Russia’s shadow fleet—primarily through deals with Greek, British, and German companies. Estimates suggest Russia has spent over $10 billion on this fleet since 2022.

Sanctions pressure has gradually intensified. The EU initially set the $60 price cap for crude oil, extended it to refined oil products in 2023, and in 2024 introduced per-voyage attestations requiring price verification for each shipment, along with stricter expense reporting. Meanwhile, G7 countries have ramped up direct action against the shadow fleet:

- In November 2024, the UK sanctioned 30 tankers.

- In December, the EU blacklisted 79 vessels.

- In January 2025, the US imposed sanctions on 183 tankers.

Beyond targeting individual ships, new US sanctions have struck at Russia’s key oil producers like never before. For the first time, Gazprom Neft and Surgutneftegaz have been placed under blocking restrictions. Additionally, the US banned American oilfield services for Russian companies, which will complicate both extraction and exports. For the first time, sanctions have also extended to oil traders and intermediaries in Asia and the Middle East, including major firms in the UAE and Hong Kong involved in reselling Russian oil.

Conclusion: Strengthening Sanctions for Real Impact

The G7 countries have imposed a significant number of strong sanctions. However, loopholes in enforcement allow Moscow to sustain its war machine, primarily through alternative markets in Asia and the shadow fleet. Without stricter control measures, the effectiveness of sanctions remains limited.

To close these gaps, the following measures are necessary:

- Targeting shipowners and operators involved in transporting Russian oil

- Stricter oversight of transshipment hubs

- Sanctions on individuals and entities linked to Russia’s defense industry

- Sanctions on companies facilitating sanctions evasion, especially in China and neighboring countries

- Restricting Russian financial institutions and energy companies (following the U.S. approach)

- Monitoring insurance operations and sanctioning insurers covering the shadow fleet

- Tracking vessels and expanding the sanctions list regularly

- Implementing geolocation tracking for sensitive equipment to block usage in restricted zones

- Enhancing coordination among allies to close loopholes and enforce penalties

- Applying billion-dollar corporate fines to companies violating sanctions, similar to penalties imposed on banks

Even in the event of a ceasefire, sanctions pressure must continue— as Russia remains a long-term security threat to Europe, and its war-driven economy requires sustained financial and technological isolation. Only coordinated, systematic tightening of sanctions can effectively disrupt Russia’s ability to fund its aggression.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations the authors may be associated with.

This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. It’s content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.