6 MB

Key Takeaways

- National Security Concerns: The Ukrainian government’s ban on the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) is driven by concerns over the Church’s ties to Russia and its potential role in undermining Ukraine’s sovereignty.

- Historical Context: The Church’s deep-rooted connection to Moscow, dating back to the Soviet era and beyond, has led to its involvement in Russian propaganda and covert activities in Ukraine, particularly during the ongoing war.

- Public Support: A significant portion of the Ukrainian population supports state intervention in the activities of the Church, viewing it as a threat to national security.

- Religious Freedom Debate: While the law has raised concerns about limiting religious freedoms, these claims are widely viewed as part of Russia’s disinformation campaign.

- Legislative Implications: The law is seen as a crucial step in curbing foreign influence in Ukraine and protecting its sovereignty, even as it sparks debate over religious rights.

On August 20th, the Ukrainian Parliament, Verkhovna Rada, enacted legislation prohibiting religious organizations’ activities with decision-making centers in Russia. This legislation primarily targets the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), addressing concerns about its activities compromising Ukraine’s national security. This has sparked controversial reactions among the public, both locally and abroad. A common feedback narrative consists of concerns regarding limitations of human rights and freedom of expression. The law regulating the activities of religious organizations aims to prevent the operation of churches governed by Russia, a state that is waging war against Ukraine. Religious organizations suspected of cooperating with the Russian Orthodox Church will be investigated by a designated expert commission, which the State Service of Ukraine will establish.

This article will examine the underlying historical data and other factors necessitating this legislative decision and draw possible consequences for the Ukrainian religious and security fabric.

Historical background

The history of Orthodoxy in Ukraine began with the baptism of Kyivan Rus in 988 under Byzantine authority. The Kyiv Metropolis remained aligned with Constantinople until the mid-15th century. Around the same time, the Moscow Metropolis became a patriarchate. Following the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, Moscow was declared the ‘Third Rome’ by the Pskov monk Philofey.[1]

The National Liberation War (1648-1657) and the Pereyaslav Agreement (1654) increased Russian dominance over Ukrainian territories. In 1686, Moscow reasserted control over the Kyiv Metropoly despite local resistance.

During the Soviet era, the church was strictly controlled, with many of the clergy persecuted or coerced into collaboration with the KGB. In 1989, the Moscow Patriarchate granted the Ukrainian Exarchate greater autonomy and the title ‘Ukrainian Orthodox Church,’ but these changes were largely symbolic, aimed at maintaining Russian influence. Today, this branch is known as the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) or UOC MP, though its connection to the ROC is often downplayed by its representatives.

In early 2019, the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (formerly known as Ukrainian Orthodox Church Kyiv Patriarchate – UOC KP) was granted a Tomos of autocephaly by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. This new church was subsequently recognized by the Churches of Greece and Cyprus, as well as the Patriarchate of Alexandria. The current situation is characterized by significant tension between the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) and the newly established autocephalous Church of Kyiv Patriarchate.

Orthodox Church in Ukraine. Source: President.gov.ua

Moscow’s Grip: Echoes of KGB and Rejection of Independence

For clarity of understanding, it would be beneficial to dive into the historical realm of connections the Soviets have carefully built between the church, its clergy, and the leadership of the Union. It would be fair to point out that the church, or what remained of this institution in the USSR, was largely used as an assistant to the KGB. The nature of religion implies repentance of the parishioners, so it was a common practice to recruit priests to work for the government.

The Russian Orthodox Church’s ties to the KGB have been on the radar of many investigative journalists for decades. However, one of the most famous cases is that of Patriarch Kirill, the current head of the Russian Orthodox Church, and his visits outside the Soviet Union, namely to Switzerland. He was appointed representative of the Moscow Patriarchate to the World Council of Churches in Geneva in 1971 at the age of 24 and held this position until 1974. Such an interest taken by the strictly secular state in international ecclesiastical affairs naturally came with a price that had to be paid by the young delegate Kirill, operating under the pseudonym “Mihailov.”[2] The mentions of Vladimir Gundyaev (Kirill’s real name) in the Swiss Federal Archive confirm that “…here it is confirmed that ‘Monsignor Kirill,’ as he is regarded to in the card, was a KGB officer.”[3] Switzerland was, at the time, an important meeting point for expats, many of whom were Christian believers. Throughout his visits abroad, Gundyaev made several connections with the Russian diaspora, seeking what could be valued as important information for the Soviet government.

(archive photo). Source: AP

Fast-forward to Ukrainian independence, when the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) was officially established in its current form. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Moscow Patriarchate granted the Ukrainian Exarchate greater autonomy, allowing it to operate as the “Ukrainian Orthodox Church.” It was provided with independence in management to an extent, considering the complex religious landscape at the time and inter-confessional conflicts. Following Ukraine’s declaration of independence on August 24, 1991, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC) sought autocephaly under Metropolitan Filaret. The Archbishops’ Council of the UOC approved this move on September 6-7, 1991, and the Local Council further endorsed it on November 1-3, 1991, requesting autocephaly from Patriarch Alexy II of Moscow. The Council also proposed the establishment of a Kyiv Patriarchate. However, the Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) denied autocephaly at its Council in Moscow (March 31 – April 4, 1992), and Filaret was urged to resign. His refusal led to the formation of a pro-Moscow faction within the UOC and subsequent persecution of his supporters.

In 1997, the Moscow Patriarchate excommunicated Filaret, who argued that the anathema was politically motivated and unjust, as it should only be imposed for heresy, schism, or moral violations. On October 11, 2018, the Ecumenical Patriarchate’s synod unanimously deemed the anathema invalid, recognizing it as politically driven. Later, Filaret commented that this decision of the ROC was purely politically motivated in order to stop Ukraine’s strife for religious independence.[4]

Ahead of the Russian Orthodox Church’s Archbishops’ Council in August 2000, which included UOC hierarchs, Ukrainian President Kuchma requested canonical independence for the UOC. The Russian Archbishops’ Council, after reviewing the request and debating the issue, chose not to grant autocephaly to avoid the so-called further division.[5]

The facts listed above are just a small part of the reasoning behind why some perceive the UOC MP as closely linked to the Russian Orthodox Church. With its close ties to the Russian government and its role in disseminating propaganda among parishioners in Ukraine, the UOC MP and its clergy have been accused of supporting Russia both ideologically and physically.

Orthodoxy at the Service of the Warmonger

In 2016, two years after the beginning of Russia’s hybrid war on Ukraine, the European Parliament, in its “Report on EU strategic communication to counteract propaganda against it by third parties,” recognized that “…the Russian Government is aggressively employing a wide range of tools and instruments, such as …cross-border social and religious groups, as the regime wants to present itself as the only defender of traditional Christian values.”[6] This has been precisely the case for the Russian warmonger raging in Ukraine, with the main tool being the Ukrainian Orthodox Church Moscow Patriarchate.

When it comes to UOC MP’s support for Russia’s actions on the sovereign territory of Ukraine, scandalous news titles are no novelty. This alignment has been evident since the initial stages of the illegal annexation of Crimea. The Security Service of Ukraine has revealed that clergy from the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) actively supported covert operations led by Igor Girkin (Strelkov), a known terrorist and orchestrator of militant groups responsible for the annexation of Ukrainian territories. Girkin’s armed group conducted reconnaissance in Simferopol under the pretense of guarding the church relics, specifically the “Gifts of the Magi.” [7]

In the occupied territories, certain clergy members have shown support for the “new order” imposed by Russian occupiers on religious life. A notable example is Mr. Konstantin Chernyshov, also known by his church title as Bishop Kalinnik, who played a significant role in the illegal annexation of Crimea. He engaged in anti-Ukrainian propaganda, established a weapons cache on the grounds of his church in the village of Uyutne, and was awarded the medal “For the Defense of Crimea” by the occupying authorities. Further on in his career, Kalinnik consecrated the naval flag and the reception of the small missile ship “Grayvoron” into the Black Sea Fleet of Russia. [8]

active participation and personal courage” shown in March

2014 during the annexation of the Crimea from Ukraine.

Within this context, it is important to note that the Simferopol and Crimean Diocese of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the Russian Orthodox Church officially broke all its connections with Kyiv, which remained increasingly formal for all eight years of the Russian annexation of Crimea. A new metropolis was created in Crimea, which included all units of the UOC MP on the peninsula. It became directly subordinated to the Russian Patriarch Kirill. [9]

The case of Chernyshev is not an isolated incident. Numerous individuals cloaked in religious garments have been actively promoting the ideology of the ‘Russian Mir’ [Russian World] under the guise of advocating for traditional values and unity. Even prominent figures within the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) have not hesitated to collaborate with the occupiers. Pavlo Lebid, commonly known as Pasha Mercedes due to his affinity for luxury vehicles, has consistently displayed a pro-Russian stance. Lebid, a former parliamentarian with the controversial Party of Regions and an ex-Vicar of the Dormition Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra, has been involved in several notable incidents. During the Revolution of Dignity, he supported violent actions of the security forces against the peaceful protesters and questioned the motives of the latter, implying their ‘paid participation.’ Additionally, he has publicly accused Ukraine of being the aggressor in the Donbas conflict. Following the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the metropolitan remarked that Ukrainians failed to heed warnings and are now “reaping what they sow.” [10]

With the beginning of the full-scale invasion, the amount of such cases multiplied rapidly. According to official data from the Security Service of Ukraine, nearly 70 criminal proceedings were initiated against representatives of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) during the first two years of Russia’s war against Ukraine. Among these cases, at least 14 involve metropolitans of the church. The crimes uncovered include 20 instances of treason, collaboration, and aiding Russia as an aggressor state. Additionally, at least 18 other proceedings pertain to the incitement of religious hatred, the illegal sale of firearms, and the distribution of child pornography. [11]

The loudest case involving UOC MP was the incident with Kyiv Pechersk Lavra in 2023. On March 29, the lease agreement between the National Reserve “Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra” and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) expired. However, the Moscow Patriarchate did not vacate the premises. On March 30, they quietly conducted a divine service at the Lavra while parishioners obstructed the work of the Ministry of Culture’s commission. Metropolitan Pavlo Lebid of the UOC MP declared that the Church would not vacate the Lavra premises, while his parishioners protested the government commission with chants like “Get out of Lavra, go to war.”[12]

the Order of Friendship for strengthening the unity of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The call to “go to war” starkly exemplifies the disregard for the prevailing political situation in Ukraine. This statement highlights the church’s and its parishioners’ disconnection from the national sentiment and the realities of the ongoing conflict, reflecting a profound insensitivity to the struggles and sacrifices of Ukrainian citizens during a time of war. This behavior also underscores how this segment of the Orthodox Church, along with a significant portion of its followers, has aligned with the Russian narrative, viewing the Russo-Ukrainian war as “fratricidal.” They have internalized propaganda, often disseminated through the speeches of Lebid and other pro-Russian clerics, emphasizing the indivisibility of the so-called “true” church and its leaders.

Beyond the cases outlined, the UOC MP, along with its clerics and parishioners, is increasingly at the center of scandalous events frequently highlighted in news outlets. This continuous exposure fuels growing resentment among segments of the Ukrainian public, who see the Church as an enemy propaganda force operating freely in a war-torn country under the guise of sanctity and untouchability.

What the Ban Means for Ukrainian Society

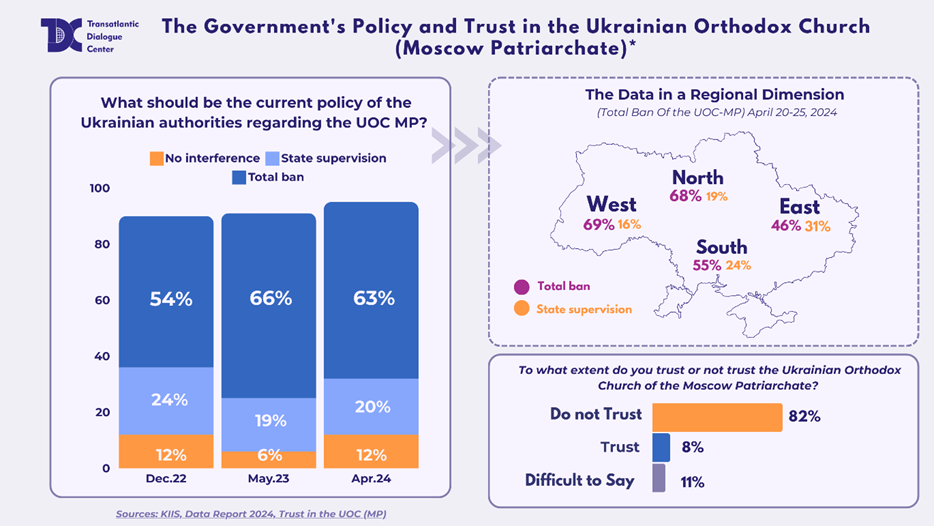

In response to the growing scandals and criminal cases involving key religious figures and the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate), the Ukrainian Parliament enacted legislation to address these concerns. This legislative action reflects the shifting public sentiment towards the UOC MP, which had been increasingly scrutinized for its connections to Russian influence and activities perceived as undermining Ukrainian sovereignty. Public opinion, captured in a survey by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, underscores the societal tensions leading up to this legal intervention.

In the graph, the data are shown in a regional dimension. In all regions of Ukraine, the majority of the population (from 76% in the East to 85% in the West and 86% in the Center) favor a proactive state position regarding the activities of the UOC (MP). [13]

A common question that concerns Ukraine’s Western partners is, “Does the new law limit the freedom of religion and human rights?” The short answer is no. This narrative is yet again a crucial part of Russian propaganda, carefully distributed by the pro-Russian agitators throughout Ukrainian and international informational space. For instance, Artem Dmutruk, a subdeacon of the UOC MP, is convinced that “After all, the prohibition of the church is not only the prohibition of legal organizations. First of all, it is a ban on a person to profess the Orthodox faith, to call himself a believer of the Orthodox Church!” Following Article 2 of the Law of Ukraine, “On the Protection of the Constitutional Order in the Field of Activities of Religious Organizations”, foreign religious organizations may carry out activities in Ukraine, provided that their activities do not harm national or public security, protection of public order, health or morals, rights and freedoms of other persons. Additionally, Article 161 of the Criminal Code, “Violation of the equality of citizens depending on their racial, national, regional affiliation, religious beliefs, disability, and on other grounds,” clearly states that there shall be no limitation of rights based on an individual’s religion. This certainly includes the ability to practice a religion as well.

The legislation aims to restrict the influence of hostile entities, particularly Russia, by limiting their ability to infiltrate Ukrainian information and public spheres. The law targets areas of society that are particularly vulnerable to subversion, where such actions might typically go unnoticed or unchallenged. By doing so, it seeks to protect Ukraine’s national security from subtle yet potent forms of external interference.

Conclusion

The Ukrainian government’s enactment of new legislation in response to the scandals and criminal activities involving the UOC MP represents a critical step in safeguarding the nation’s security during a time of war. This law aims to limit the infiltration of Russian influence within Ukraine’s informational and public domains, areas where Russia has sought to exploit vulnerabilities. As can be seen from all the evidential cases, Verkhovna Rada had a solid basis for the law’s enactment.

Although the legislation has sparked concerns over potential infringements on religious freedom and human rights, many of these claims appear to be fueled by Russia’s harmful narratives. The law is a strategic response to protect Ukraine’s national security by curbing the influence of the Russian Orthodox Church, which has been implicated in supporting Russia’s actions in Ukraine. The Ukrainian government views this legislation as essential for preserving sovereignty and countering propaganda, even amid the complex debates surrounding religious rights. The new law underscores the necessity of protecting national sovereignty against external threats. This decisive action reflects Ukraine’s commitment to maintaining its territorial integrity and resilience in the face of ongoing aggression.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations the authors may be associated with.

[1] John Strickland, The Making of Holy Russia: The Orthodox Church and Russian Nationalism Before the Revolution (Jordanville, NY: The Printshop of St Job of Pochaev, 2013), 12-13.

[2] Sylvain Besson, Bernhard Odehnal, “Putins Patriarch war Spion in der Schweiz,” Tages-Anzeiger, February 14, 2023, https://www.tagesanzeiger.ch/priester-spion-propagandist-das-geheime-leben-des-moskauer-kirchenfuersten-in-der-schweiz-566103963787.

[3] Aleksandra Ivanova, “Агент КГБ? Что именно узнали в Швейцарии о патриархе Кирилле [KGB agent? What exactly they learned in Switzerland about Patriarch Kirill],” DW – Made for minds, February 7, 2023, https://www.dw.com/ru/agent-kgb-cto-imenno-uznali-v-svejcarii-o-patriarhe-kirille/a-64621841.

[4] Glavkom, “Філарет пояснив, чому Вселенський патріархат заговорив про анафему Мазепі [Filaret explained why the Ecumenical Patriarchate spoke about the anathema of Mazepa],” September 22, 2018, https://glavcom.ua/news/filaret-poyasniv-chomu-vselenskiy-patriarhat-zagovoriv-pro-anafemu-mazepi-529946.html.

[5] RISU, “Українська Православна Церква (Московського Патріархату) [Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate)],” June 17, 2011, https://risu.ua/ukrajinska-pravoslavna-cerkva-moskovskogo-patriarhatu_n48337/amp.

[6] Anna Elżbieta Fotyga, “Report on EU strategic communication to counteract propaganda against it by third parties,” Report – A8-0290/2016, Committee of Foreign Affairs, EP, October 14, 2016, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/A-8-2016-0290_EN.html.

[7] Radio Svoboda, “УПЦ (МП) допомагала Гіркіну готувати анексію Криму – СБУ [UOC (MP) helped Girkin prepare the annexation of Crimea – SBU],” December 10, 2018, https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/news-upts-mp-dopomohala-hirkinu-v-aneksii-kymu-sbu/29648587.html.

[8] Dmytro Huliychuk, “Єпископ УПЦ МП в окупованому Криму освятив російський корабель і назвав РФ “богохранимою вітчизною” [The bishop of the UOC MP in the occupied Crimea consecrated a Russian ship and called the Russian Federation a ‘God-protected homeland’],” TSN, February 28, 2021, https://tsn.ua/ukrayina/yepiskop-upc-mp-v-okupovanomu-krimu-osvyativ-rosiyskiy-korabel-i-nazvav-rf-bogohranimoyu-vitchiznoyu-1735411.html.

[9] Serhiy Mokrushyn, “«Церковна анексія». Як кримські єпархії УПЦ МП перейшли до РПЦ, і чи остання це втрата для церкви [Church annexation. How the Crimean dioceses of the UOC-MP transferred to the Russian Orthodox Church, and is this the last loss for the church],” Krym Realii, June 9, 2022, https://ua.krymr.com/a/krym-tserkva-perepidporiadkuvannia-moskovskomu-patriarkhatu/31890688.html.

[10] Artur Gmurya, “За що заборонили УПЦ МП — ТОП гучних справ проти священників московських церков [Why was the UOC MP banned — TOP high-profile cases against priests of Moscow churches],” P9, August 20, 2024, https://thepage.ua/ua/politics/yak-svyasheniki-upc-mp-dopomagali-rosijskim-okupantam.

[11] Inna Semenova, “Заборона УПЦ МП. Що важливо пам’ятати про скандали навколо цієї церкви та її зв’язок з РПЦ під час вторгнення Росії [Prohibition of the UOC MP. What is important to remember about the scandals surrounding this church and its connection with the Russian Orthodox Church during the Russian invasion],” New Voice, August 20, 2024, https://nv.ua/ukr/ukraine/politics/zaborona-upc-mp-yaki-skandali-cerkvi-nayvidomishi-i-yak-vona-pov-yazana-z-rpc-novini-ukrajini-50420660.html.

[12] Apostrof, “Скандал з УПЦ МП у Києво-Печерській лаврі: всі подробиці [The scandal with the UOC MP in the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra: all the details],” March 31, 2023, https://apostrophe.ua/ua/news/society/2023-03-31/skandal-s-upts-mp-v-kievo-pecherskoy-lavre-vse-podrobnosti/294121.

[13] Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, “What should be the government’s policy and trust in the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate),” May 7, 2024, https://kiis.com.ua/?lang=eng&cat=reports&id=1404&page=1.