2 MB

Key Takeaways

- Human Capital Importance: Facilitating the return of Ukrainian refugees is essential for Ukraine’s long-term economic recovery and growth.

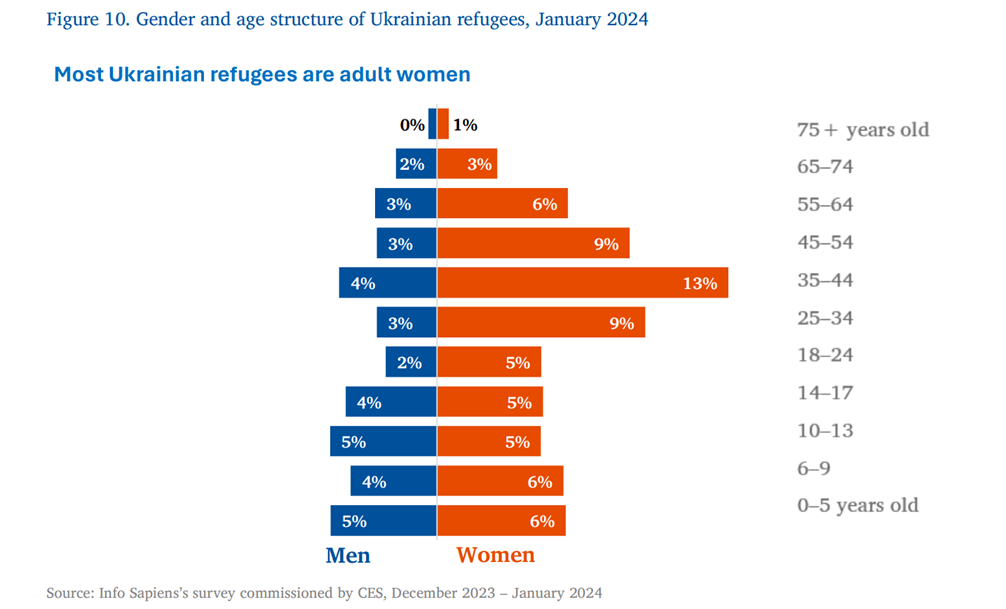

- Demographic Impact: The war has led to a significant reduction in Ukraine’s labor force, with millions of refugees, primarily women and children, now residing in Europe.

- EU’s Role: European countries, especially Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic, have become major destinations for Ukrainian refugees, offering varying levels of support and integration.

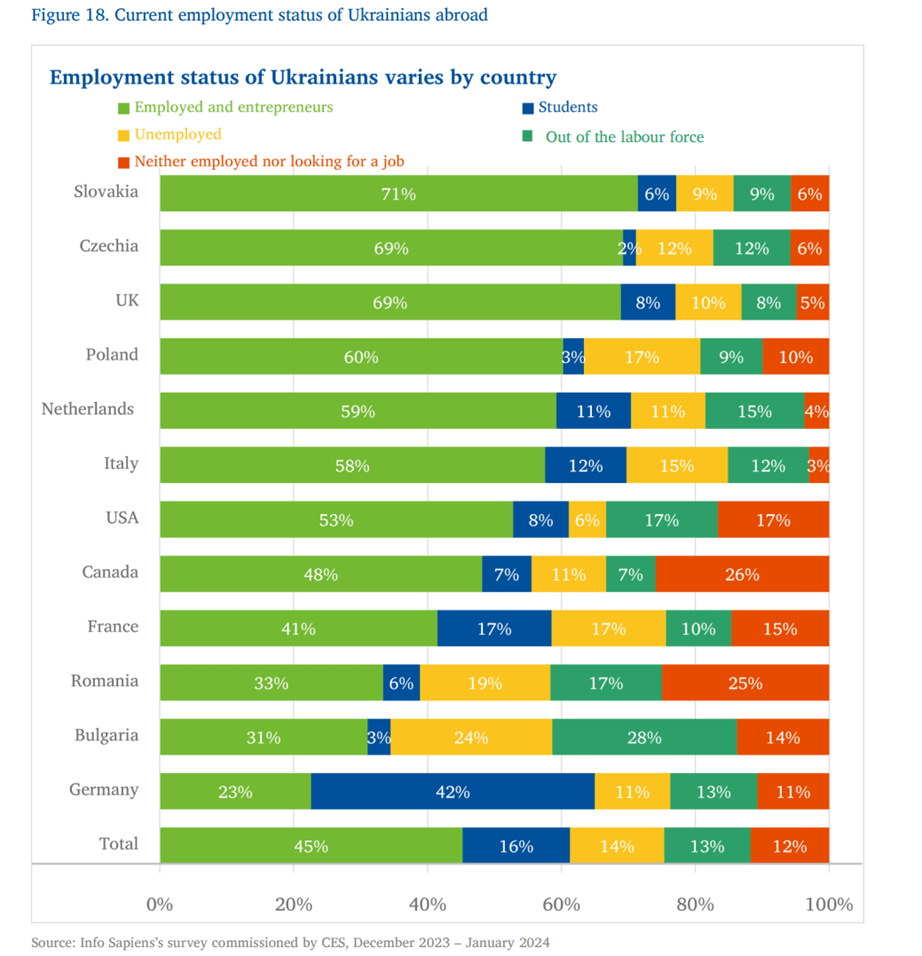

- Integration Strategies: There is a shift in the EU from providing temporary refuge to fostering socioeconomic integration, with successful models like that of the Czech Republic serving as benchmarks.

- Communication Gaps: Effective communication from the Ukrainian government is crucial to maintaining refugees’ connection to their homeland and encouraging their return.

- Policy Reforms Needed: Ukraine must implement comprehensive strategies and immediate reforms in areas such as economic development, rule of law, and military service to enhance prospects for refugee return.

Crisis damages society, and its consequences can be more far-reaching than one might expect. Hence, during times of war, discussions about military aid are accompanied by talks about reconstruction plans, and the human dimension becomes an integral part. Human capital is one of the main prerequisites for the long-term prospects of a country’s economic growth. That is why it is already a regular topic of the Ukraine Recovery Conference, another traditional event in the political calendar established after the beginning of the Russian war. Indeed, the subject is complex, as the interests of different parties, in particular Ukraine and the EU, intertwine delicately in this matter.

In this article, we will examine the current situation with Ukrainian refugees, the peculiarities of their stay in the EU, and the prospects of the Ukrainian government’s plans to return its citizens home.

Portrait of a Ukrainian Refugee

An average Ukrainian refugee is a woman aged 35-44 who left her country with a child.

According to UNHCR, in June 2024, around 6,554,800 Ukrainian refugees were recorded globally. Women accounted for 65% of all refugees abroad as of January 2024. The vast majority of them (71%) left with their children. Men make up 35% of refugees. Most of the departed Ukrainians came from the southern and eastern regions of Ukraine, where the security situation is the most precarious. According to the Centre for Economic Strategy, a leading Ukrainian think tank, in terms of individual regions, the leader is the Kharkiv region (15.2% of respondents), followed by Kyiv (13.3%) and the Kherson region (9.6%).

Since no one knows when the war will end, it is only natural that people are gradually settling down into their new places, leading to the annual decrease of the share of Ukrainians who wish to return home. Thus, as of the spring of 2024, only 26.2% of Ukrainian refugees were convinced that they would go back, compared to 49.7% in the autumn of 2023. The harm caused to the Ukrainian economy is salient. Against the backdrop of demographic losses due to the occupation of territories and war casualties, the labor force aged 15-70 decreased by more than a quarter from 2021 to 2023.

Europe became the main point of relocation of Ukrainians, hosting around 6,021,400 refugees as of July 15, 2024. It is worth mentioning that EU countries provide significantly more support for Ukrainian refugees than those outside the bloc. According to Eurostat, the largest number of Ukrainians who fled the war are located in Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic. At the same time, the trends in flows remain dynamic: in 2022, the majority chose Poland as the final destination due to its proximity to Ukraine, while in 2023, more and more Ukrainians aspired to reach Germany. According to reports, this change was caused by both economic factors (higher salaries and better social security) and social factors (based on friends’ advice for family reunification).

Pragmatic Good Samaritan: EU Policies on Ukrainian Refugees

There are currently two scenarios that apply to Ukrainians fleeing to the EU: they can either apply for refugee status or for temporary protection. While refugee status grants permanent residence in the territory of the respective state, temporary protection status, regulated under the EU 2001 Temporary Protection Directive, provides a sort of temporary refuge. The procedures to obtain the status are different, but in general, obtaining refugee status is far more complex and restraining. On top of this, an asylum application implies the withdrawal of a passport before the expiration of the 6-month period and the absence of access to the labor market. However, it is worth noting that very often, official documents do not make a distinction between refugees and temporary protection beneficiaries, referring to both groups in the same way.

Granting temporary protection to Ukrainians is an exceptional measure. Established to overcome “mass influx” following armed conflict in the Western Balkans, it was not invoked until Russia launched war against Ukraine. All EU countries except Denmark are subject to the Directive. Nevertheless, Copenhagen introduced a similar status via national legislation. Unlike refugee status, temporary protection status provides Ukrainians with higher levels of mobility, as they can move freely inside the Union for up to 90 days within a 180-day period and may return to Ukraine on a temporary basis. Besides, Ukrainians are eligible to re-apply for temporary protection status if they’ve lost it previously, though this procedure is not offered in all EU countries. As it is much quicker to get a residence permit and access to the labor market and housing under the Temporary Protection Directive than under ordinary asylum procedures, many believe that Ukrainians are treated better than other refugee nationals. However, the attitude towards Ukrainian refugees and, subsequently, the conditions of stay offered vary from country to country.

Temporary protection is not a permanent mechanism: it is subject to prolongation, and its duration, according to the Directive, is three years. Notwithstanding, the EU Council has already extended temporary protection for Ukrainian refugees until 4 March 2026. However, the situation with further extension is unclear. European politicians agree that until the end of hostilities, canceling temporary protection must not be an option, but if the war drags on, the conditions for the implementation of the Directive will definitely change. Frankly speaking, they’re already changing.

Over the past year, cuts in social assistance and other related limitations have become more common among EU countries. The main reason is the changed treatment of Ukrainian asylum seekers. Since no one expects the war to end at once, every year, it becomes more problematic for European countries to support the ever-increasing number of refugees. Lack of funds and the housing crisis are some of the most important challenges Europe is facing. Therefore, many countries wish to enhance the socioeconomic inclusion of refugees, bolstering self-reliance among them by reducing support. Besides, integrating Ukrainian refugees is a part of the strategy for attracting skills and talent to the EU. Ukrainian migrants can fill the gaps in the labor market caused by labor shortages.

Such an approach matches UNHCR’s recommendations for higher levels of integration under its Ukraine Situation Regional Refugee Response Plan. This policy certainly may increase the number of cases of no-returns in Ukraine. Nevertheless, resorting to it has always been a common case throughout the history of conflicts and migration. Usually, this policy is employed in countries initially interested in accommodating refugees: for example, after the Yugoslav Wars, refugees’ labor force participation was higher in those host countries that provided access to the labor market and/or permanent residency. Officially, EU countries assert that maintaining and enhancing the skills of professionals among refugees can help accumulate valuable resources for their return and reintegration into their homeland.

At the same time, another aim of the stricter stay rules under the Temporary Protection Directive is to encourage Ukrainians who are not prepared to work in the new state to return home. So far, only Norway and Switzerland, non-EU countries, have offered money for repatriation. Similar schemes have been discussed and devised in Ireland. The Czech Republic became the first EU member to launch a pilot project to cover transport expenses for Ukrainians on their way back to the motherland in June 2024.

In the meantime, European politicians are thinking about durable solutions to accommodating Ukrainians after the termination of the Directive, for example, by granting long-term residence permits. Currently, although such a permit may be given after five years of residence on the territory of the EU state according to the 2003 Long-term Residents Directive, it doesn’t apply to nationals who reside under the Temporary Protection Directive. Nevertheless, this item is being negotiated. At the national level, only the Czech Republic already drafted amendments to allow Ukrainians with temporary protection to obtain a long-term residence permit, provided that they are economically self-sufficient.

As you may observe, Prague boldly introduces new measures in terms of migration from Ukraine. Perhaps due to this, the Czech Republic became the first country where refugees bring more income than the state spends on social assistance: in the first quarter of 2024, revenues to the budget from refugees almost doubled expenditures). Other EU states have taken the Czech Republic’s success into account and are ready to develop their own projects for the accelerated integration of Ukrainian refugees: for example, Germany has introduced a Job Turbo program for the integration of Ukrainian refugees right after acquiring basic language skills.

The employment situation among Ukrainians is rather dynamic. The share of employed Ukrainians is constantly increasing and varies between countries. At the beginning of 2024, approximately 45% of all refugees were employed, and 16% were students. Slovakia, the Czech Republic, the United Kingdom, and Poland became leaders in terms of employment of Ukrainian refugees – employed constitute 60-70% of all refugees. In countries where Ukrainians’ access to the job market is subject to restrictions, the share is lower. Besides, many refugees complain that finding work in countries with rising unemployment (like Spain or Finland) is almost impossible due to high levels of competition.

Paving the Way Home: Ukraine’s Efforts to Bring Its Refugees Back

Against the background of a mass exodus of Ukrainians abroad, the concerns about the irreversible loss of manpower are becoming more justified and urgent. As a result, Ukraine is already engaging in talks with EU countries, calculating possible ways to foster the return of Ukrainians. According to the UNHCR “no return” advisory, the large-scale return of Ukrainians is possible only after the stabilization of the country’s security situation. However, particular media hints that Ukrainian officials are already pressing the EU establishment to introduce more limitations at the national level to foster inflows of returnees. Ukrainian officials refuse to formally authorize such a course of policy. Nevertheless, European diplomats have repeatedly stated that decisions on Ukrainian migrants will be made in close consultation with Kyiv, so Ukraine’s vision of refugee return policy is a key factor in the European policy-making process.

And this is where the difficulties arise.

Ukraine’s detailed state policy on this issue has yet to be articulated. Kyiv has stressed several times that no administrative methods shall be used to force the return of displaced Ukrainians, but well-defined strategies are still underway. The most promising project is the Ministry of Economy’s refugee return program, which views remigration as a four-sector task. Identified areas for improvement include state security, access to the labor market, housing, and higher-quality education. It has been alleged that accommodation and work opportunities can already be covered by the existing programs “eOselia” and “eRobota” (roughly translated as “there is Home” and “there is Work”). However, this is basically what the public program description is limited to. This does not mean that Ukraine is doing nothing in this area while waiting for the document to be finalized. For example, this June, Ukraine and the EU launched the Skills Alliance for Ukraine Initiative to train workers for possible engagement in post-war reconstruction. The issue is that such thematic projects are not conducted as part of the program implementation but are presented as separate initiatives. In other words, the program is being implemented in essence, but in fact the document itself is still not adopted.

new careers. Source: Cherkasy Regional State Administration

It must be noted that Ukrainian experts have always criticized the government for insufficient measures taken in the field of migration, which led to a negative migration balance even prior to the war. The 2017 Migration Strategy was considered as not having been executed thoroughly. The decision to grant Ukraine EU candidate status had a positive impact on the situation. In January 2024, the Migration Strategy was amended, setting new objectives to create conditions for the smooth return of Ukrainian refugees. The approach to migration itself has become more comprehensive, which has brought it closer to the EU’s updated approach. However, Ukraine is now faced with the task of implementing the prescribed clauses, which is particularly difficult due to limited resources. That is why it is important for Ukraine to properly organize communication with citizens abroad.

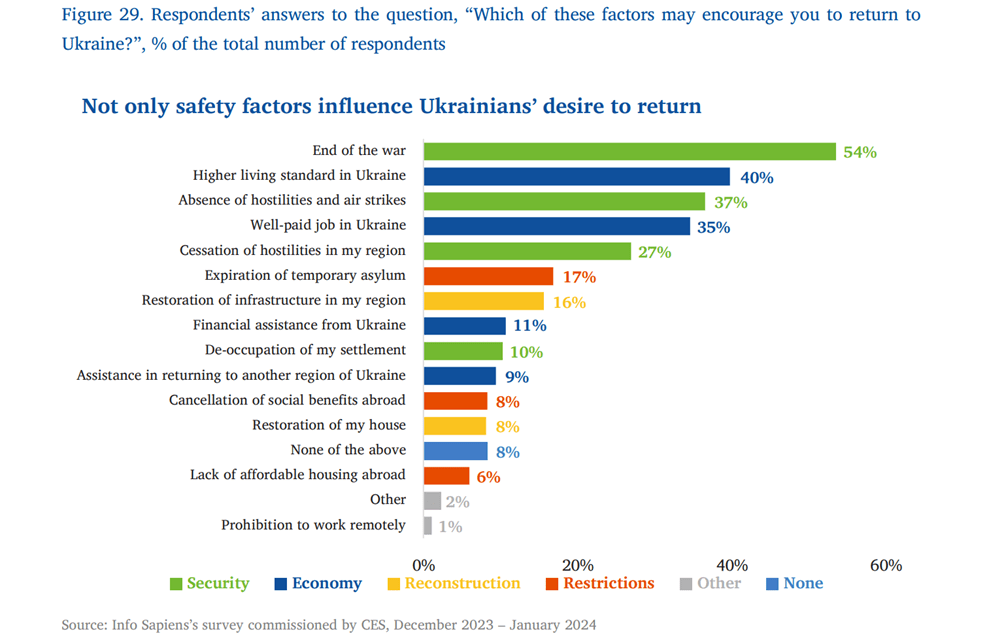

Besides, there’s something more to consider. The present situation on the frontline prevents any discussion about establishing favorable conditions for the return of refugees. Thus, it is impossible to consider a stable security situation as a prerequisite for the permanent return of Ukrainians for the foreseeable future. Given that, it goes without saying that to keep Ukrainians willing to come back, it is urgent to adjust and improve existing Ukrainian policies. Postponing solutions and changes in the laws until the end of war limits the success of the return policy since such issues as lack of normalized reservation from military service and adequate communication on this topic already worsen the prospects of return in the long run.

A Trap of Insufficient Communication

What do Ukrainian refugees know about the current situation in their country?

Amidst discussions on refugee return strategies and programs, this question always remains barely touched upon. All initiatives and discourses traditionally focus on practical changes in life quality. It seems to be often forgotten that it is the refugee who makes the final decision whether to stay in the country. Consequently, no upgraded social policy or business support program will be able to persuade a person to return if they initially do not see their future in the country. That is precisely the reason why sustainable refugee return demands an advanced communication strategy.

Failure to communicate properly with refugees can have long-term negative consequences. Since the Ukrainian government negotiates with refugees from a weak position (due to the impossibility of providing safe living conditions), it should be very careful when choosing the messages to be broadcast. The most important task is to avoid narratives emphasizing the exclusion of refugees, as it will lead to their further alienation. In addition, such statements contribute to the polarization of society. For example, during New Year’s Greetings 2024, President Zelenskyy addressed refugees: “One day you will have to ask yourself: who am I? And make a choice: whom do I want to be? A victim or a victor? A refugee or a citizen?”. This sparked a discussion on social media: most Ukrainians who stayed in the country supported the president’s words, while many refugees interpreted the statement as an accusation.

It is important to understand that not all Ukrainians can return home as soon as the security situation stabilizes. According to the Centre for Economic Strategy, 5% of refugees have their homes completely destroyed (the largest number of such refugees live in Germany – 7%), and 19% have damaged homes that can be restored (the largest number of such refugees live in the UK – 28%). It is clear that the main conditions for their return are a guaranteed place of residence and job opportunities with a high salary.

As for day-to-day communication with refugees, the current level of occasional communication is definitely not enough. The main sources of information for Ukrainian refugees remain social and mass media, which are dominated by news about shelling, combat losses, and economic recession. And since the state provides little to counter the negative impact of pessimistic news, Ukrainians are losing the motivation to return.

We are already witnessing the consequences of inadequate communication with refugees: one-third of Ukrainian refugees currently living in Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic are not interested in the situation in Ukraine. These people may already be considered lost to the Ukrainian labor market in the near future.

A comprehensive strategy should include measures for both supporting bonds with refugees who plan to return and maintaining ties with migrants. Given the high risk of no return, it is crucial to use the lobbying potential of the new Ukrainian diaspora to the fullest. Policy-making on the engagement with Ukrainian nationals in Germany, the Czech Republic, and Poland, where Ukrainian refugees are most numerous, should be prioritized.

Conclusions

The Ukrainian economy has suffered significantly from migration, with the labor force aged 15-70 decreasing by over a quarter from 2021 to 2023. Since no one knows when the war will end, the share of Ukrainians who wish to return home has been decreasing annually. Europe, especially Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic, has been the primary destination for Ukrainian refugees, with trends shifting towards Germany due to better economic opportunities and social factors.

However, European countries are facing challenges in supporting the growing number of refugees. To address the issues, there has been a shift from a mere temporary refuge approach to a socioeconomic integration strategy. Successful pioneering of new measures for the economic integration of Ukrainian refugees by countries like the Czech Republic already influences policies in the other EU states.

For Ukraine, it’s necessary to develop strategies for the return of refugees. The Ministry of Economy’s refugee return program should be finalized for better coordinate efforts. Postponing reforms on economic development, rule of law, and military service until the end of the war limits the success of the return policy and worsens the prospects of return in the long run. Devising a wise communication strategy with Ukrainian refugees is crucial to secure their return in the long term.

No matter what reasons the nations of the world are fighting for, human life remains the most valuable asset. Only human beings can conceive something new and give birth to an idea that could change the environment. That is why sufficient human capital is one of the main conditions for countries’ prosperity. Skilled labor will always be in demand. Ukraine should start to prepare solid grounds to welcome its returnees not only spiritually but also materially.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations the authors may be associated with.