3 MB

Key takeaways

- Biological weapons are emerging as one of the most dangerous threats to global security, uniquely capable of causing mass disruption, yet still underestimated in strategic planning.

- The COVID-19 pandemic served as a real-world warning, exposing how even advanced nations lacked the infrastructure, coordination, and resilience to handle a fast-moving pathogen. These same vulnerabilities would be even more catastrophic if exploited intentionally, through a weaponized biological agent.

- Global biosecurity remains dangerously uneven: while countries like the U.S. and U.K. have advanced capabilities and infrastructure, much of the world lacks basic diagnostic systems or legal frameworks. This disparity creates global weak points that can be exploited by state or non-state actors.

- At the same time, adversarial powers such as Russia and China are expanding their biotechnology programs with dual-use potential, including possible offensive applications, while flouting existing arms control norms.

- New technologies such as synthetic biology, CRISPR, and AI are rapidly lowering the barriers to designing or modifying pathogens, making it increasingly plausible that small groups—not just nation-states—could develop and deploy bioweapons.

- The absence of meaningful enforcement mechanisms in the Biological Weapons Convention and the lack of a global oversight body equivalent to the IAEA leave the world ill-equipped to detect or prevent such threats.

- The window for effective prevention is narrowing. To counter this risk, Western governments must treat biodefense as a core element of national and alliance security, investing in early warning systems, interoperable stockpiles, high-containment labs, and international governance. Without such measures, the next outbreak may not come from nature, but from a deliberate act, with consequences far beyond a public health emergency.

Biological weapons represent one of the gravest threats to global security, and paradoxically, one of the most overlooked. Unlike nuclear or conventional arms, bioweapons harness infectious agents (viruses, bacteria, toxins) to cause disease, death, and societal disruption. They can spread invisibly and exponentially, which is why they’re sometimes called the “poor man’s nuclear bomb.” A single release, if timed and placed right, could spark a catastrophic pandemic.

We’ve all just lived through a pandemic with COVID-19, which, although natural in origin, starkly illustrated what a contagious pathogen can do. Over 7 million people have died, economies shut down, and even powerful governments were caught off guard in the face of a new virus. If a bio-attack were deliberate – say, an engineered strain with higher lethality – the consequences could be even more devastating.

COVID-19: A Wake-Up Call for Biosecurity

The pandemic exposed the world’s startling lack of preparedness. COVID’s ~2% fatality rate devastated societies, health systems were overwhelmed, global supply chains broke, and misinformation flourished. In early 2020, we saw a scramble for basic protective gear: masks, personal protective equipment, and ventilators. An advanced bioengineered agent might do worse.

The Global Health Security Index had warned in 2019 that most countries were not ready for a serious outbreak; indeed, the majority scored below 50 on a 100-point preparedness scale. Those warnings were largely ignored. An independent board of experts literally titled their 2019 report “A World at Risk,” urging action against pandemics. Yet in 2020, it became clear that even wealthy nations lacked coordinated response plans, and many poorer nations had almost no capacity at all.

COVID-19 was a watershed moment for biosecurity awareness. It forced leaders and the public to confront the nightmare scenario of a fast-moving pandemic. While COVID itself wasn’t a deliberate attack, it highlighted exactly the kind of impacts a biological weapon could inflict. Entire cities locked down, hospitals overflowing, travel halted, misinformation running rampant. Many countries that thought they were secure realized they were woefully underprepared. Even in NATO and the EU, initial responses were ad hoc and fragmented, revealing a strategic blind spot in security planning.

There were some improvements spurred by the crisis – governments started investing more in public health and pandemic preparedness after seeing the fallout. Initiatives like the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, gained prominence for accelerating vaccines, and the EU created HERA, a new Health Emergency Preparedness Authority, to coordinate biomedical countermeasures.

However, those steps, while positive, are not nearly sufficient. Structural weaknesses persist. Biosecurity governance remains fragmented and under-resourced, especially compared to traditional military defense. Before COVID, few national security strategies truly prioritized pandemics or bioweapons. The wake-up call has been heard, but have we really acted? Some nations updated their plans or held more drills, yet others quickly slipped back into complacency once cases waned.

The Global Biosecurity Gap

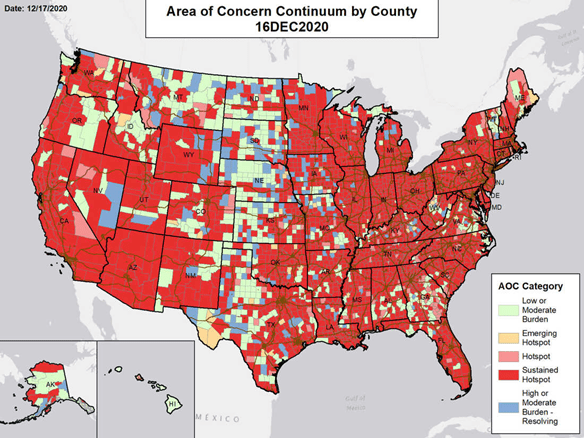

areas of concern due to COVID-19, December 2020.

Source: Department of Health and Human Services

Comprehensive indices have revealed deep disparities in global preparedness for biological threats. Only a minority of countries scored well in readiness assessments, and even top performers like the United States and the United Kingdom struggled in practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. On one end of the spectrum, wealthy nations such as the U.S., Canada, and the UK have invested billions in biodefense infrastructure, maintaining networks of Biosafety Level-3 and Level-4 laboratories, stockpiling medical countermeasures, and supporting specialized agencies like BARDA and DARPA. The U.S. Department of Defense further elevated biological threats as a national security concern in its 2023 Biodefense Posture Review.

In stark contrast, large parts of the world, including many African countries, as well as regions in Asia, Latin America, and conflict zones, lack even basic diagnostic capabilities or biosafety legislation. According to the WHO, over 70% of African nations do not have adequate legal frameworks or high-level labs to manage dangerous pathogens. This creates a dangerous global imbalance. A pathogen does not need a visa: an outbreak in a poorly prepared country can quickly spread worldwide, especially if malicious actors exploit these weak links. Addressing this vulnerability demands investment in global capacity. We need to build preparedness worldwide, not just in our own backyard.

Adversaries and Asymmetric Threats: Russia, China, and the New Bio-Politics

Moreover, adversarial regimes such as Russia and China may take advantage of these disparities. The countries have significantly ramped up investments in biotechnology and bioscience, often with dual-use intentions that raise red flags for global security. China has elevated biotechnology to a strategic national priority, reportedly exploring military applications of gene editing and synthetic biology. Their military strategists have even described biology as the “new domain of warfare,” indicating they foresee potential offensive uses of emerging biotech.

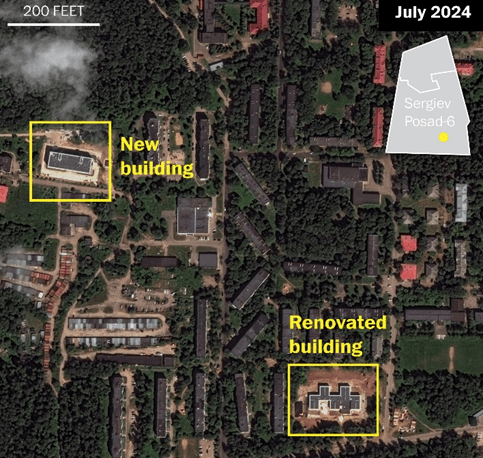

expansion of its bioweapons complex.

Source: The Washington Post

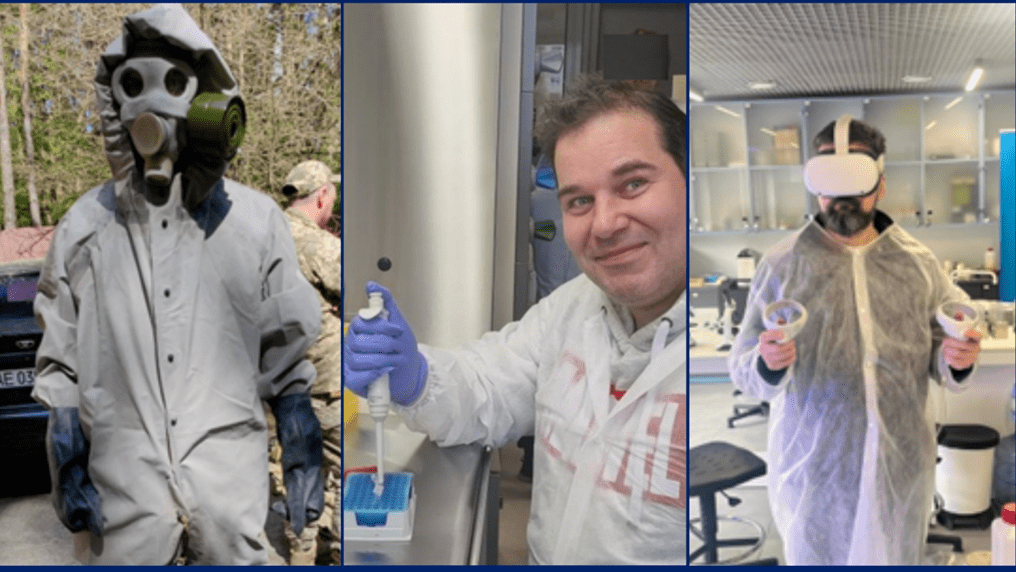

Russia remains an equally concerning actor, drawing from its Soviet legacy of secret bioweapon programs. Just recently, satellite images showed a major expansion of a once-dormant Soviet-era bioweapons complex in Sergiev Posad-6, complete with new BSL-4 labs for Ebola and other deadly viruses. Moscow claims it’s for defensive research, but Western intelligence is rightly wary.

All this suggests that while the West largely stepped away from offensive bioweapons after the 1975 Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), some regimes may not have. The playing field could be uneven, and that’s dangerous.

Sadly, the old notion that “bioweapons are not used because of a strong moral taboo” is eroding. Over the last decade, we’ve seen repeated violations of the Chemical Weapons Convention. Syria’s regime repeatedly used nerve agents and chlorine gas against civilians, shattering norms the world thought were inviolate. International investigators confirmed at least 17 instances of chemical attacks in Syria, even after it joined the Chemical Weapons Convention. Russia, too, has flouted taboos – using a banned Novichok nerve agent on UK soil in 2018 to poison Sergei Skripal, according to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) findings. And again, a Novichok-type agent was used on Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny in 2020. North Korea employed VX (another nerve agent) to assassinate Kim Jong-nam, the eldest son of Kim Jong Il, in a Malaysian airport in 2017. These examples are chemical weapons, not biological, but they are canaries in the coal mine. Any state willing to ignore global treaties on chemical arms might also ignore the bioweapons ban if it suits their goals.

Bioweapons in the Age of Hybrid War and Disinformation

In hybrid warfare, which blends military, covert, and psychological tactics, a biological attack is an especially appealing option for aggressors. It is deniable by nature – an engineered outbreak can be disguised as a natural event or blamed on an accident. Unlike a missile strike, a spreading pathogen doesn’t announce who released it. And that ambiguity is precisely what makes biological weapons so attractive to actors like the Kremlin. If cornered or seeking asymmetric leverage, they might consider unleashing a pathogen to sow chaos under the veil of plausible deniability.

We’ve already seen disinformation tactics deployed in this domain. Russia has not only shown brutality on the battlefield but has also accused Ukraine of operating bioweapons labs—an irony that fits the broader pattern of accusing others of what one might do oneself. In Ukraine, there has been no documented use of biological weapons, but the rhetorical groundwork for such justification has been laid.

Hybrid war is ultimately about exploiting every vulnerability, and in the 21st century, a plague is one of the most potent vulnerabilities. Societies under biological siege are fragile. COVID-19 offered a preview: mask mandates and vaccination campaigns became flashpoints of political polarization in the West. Anti-vaccine propaganda and conspiracy theories flourished, inflaming mistrust in governments and public health institutions. In a deliberate bioweapons scenario, this could be taken even further. An adversary could release a pathogen while simultaneously flooding the information space with rumors that the disease was man-made, that vaccines are poison, or that it’s a false-flag operation orchestrated by one’s own government.

Such a one-two punch—pathogen plus propaganda—has the potential to paralyze the response and fracture societies from within. We must not only prepare for the next pathogen, but for the accompanying infodemic. A sophisticated biological attack in this century might not resemble a Hollywood “outbreak” alone. It could arrive hand-in-hand with a disinformation and cyber campaign aimed at deepening confusion, delaying countermeasures, and eroding public trust just when unity is most needed.

Tech-Enabled Biothreats: From CRISPR to AI-Designed Pathogens

Another challenge we must highlight is how emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence and synthetic biology are lowering the barriers for developing biological weapons.

Not long ago, engineering a deadly pathogen required a state-run program with vast budgets and elite expertise. Today, thanks to advances in gene editing, DNA synthesis, and AI-driven bioinformatics, smaller groups, or even lone actors, can potentially design or enhance pathogens. AI tools can now algorithmically search for toxic biochemicals or virulent genetic sequences. In a 2022 thought experiment, researchers repurposed an AI model originally designed for drug discovery: within six hours, it generated 40,000 hypothetical toxic molecules, including novel VX variants. Applied to pathogens, such tools could identify ways to make viruses more transmissible or resistant to vaccines. This is no longer science fiction. AI-designed proteins already exist; AI-designed pathogens are increasingly conceivable.

Meanwhile, synthetic biology allows anyone with a credit card and an internet connection to order custom DNA. Gene synthesis services are readily available – you can literally mail-order pieces of smallpox or poliovirus DNA sequences. A person with ill intent and moderate lab skills could potentially assemble a lethal virus from scratch using published sequences. In fact, in 2018, scientists proved this by synthesizing horsepox (a relative of smallpox) entirely from DNA fragments, just to show it was possible.

The cost of DNA synthesis has plummeted over the last decade, and techniques like CRISPR gene-editing are cheap and widespread. Cloud laboratories and do-it-yourself biohacker spaces mean cutting-edge experiments aren’t confined to government installations anymore. This democratization of biology has undeniable upsides, faster vaccines, and personalized medicine, but it also democratizes the capacity to cause mass harm. We’re in an era where a small team could attempt what only governments could do in the Cold War. The security dilemma is clear: these tools are in the public domain, and we cannot “uninvent” them.

Legal and Ethical Gaps: Why the BWC is Not Enough

The legal and ethical gaps in global biodefense governance are stark. The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC)—while foundational in banning the development and stockpiling of bioweapons—remains toothless in enforcement. Unlike nuclear arms control, there is no international equivalent to the IAEA for biological threats. For decades, proposals to create a verification regime have been blocked, often over concerns about industrial espionage or the false sense of security they might create. As a result, if a country violates the BWC, it is extremely difficult to detect, let alone punish. Intelligence agencies and defectors remain the primary sources of insight, an unstable and insufficient system.

Even when violations are exposed, responses are often reactive and fragmented. Syria’s repeated use of chemical weapons, Russia’s deployment of Novichok agents in the UK and against Alexei Navalny, and North Korea’s assassination using VX—all were met with sanctions or diplomatic expulsions, but not with systemic international enforcement. These incidents, though involving chemical weapons, highlight a pattern: when powerful states flout arms control norms, consequences are minimal and inconsistent. If such behavior persists with chemicals, there’s no reason to assume bioweapons would be treated more seriously.

To reduce these risks, transparency and confidence-building are essential. Democracies should lead by example—openly publishing their biodefense research, inviting international observers to visit high-containment labs, and sharing data on outbreaks. These measures can pressure other nations toward openness and reduce the cover under which illicit programs operate.

The private sector must also be engaged. Many of the most cutting-edge developments in biotech occur in academic labs or startups. There is a strong case for establishing global guidelines for gene synthesis screening (e.g., checking DNA orders for dangerous sequences) and requiring ethical oversight of AI models used in biology. A UN Biological Security Council could serve as a coordinating body, bringing together scientists, regulators, and diplomats to assess emerging threats and recommend safeguards.

Source: Council on Strategic Risks.

Existing frameworks like UN Security Council Resolution 1540 already obligate countries to prevent non-state actors from acquiring WMDs, including bioweapons. Yet enforcement remains lax, and many countries still lack the domestic laws to comply.

The world urgently needs a modernized approach to biodefense governance—one that matches the pace and scope of technological change. But such reform requires trust and consensus, two ingredients that are increasingly scarce in today’s geopolitical climate.

Without bold leadership and innovative thinking, the international community will remain dangerously exposed to the next biotech-enabled threat.

What the West Must Do: Building a Modern Biodefense Strategy

In the meantime, Western countries and alliances can take practical steps to shore up defenses. Let’s pivot to solutions and what we can do proactively. From this analysis, several key themes emerge:

- Develop a Unified NATO-EU Biodefense Doctrine

Biological threats must be recognized as top-tier strategic risks, not merely public health concerns. NATO’s latest Strategic Concept should explicitly incorporate biothreats and bio-defense coordination. Right now, each member state is doing its own thing – that’s inefficient and leaves gaps. A common NATO-EU biodefense doctrine could set standards for preparedness, like interoperable stockpiles of vaccines and tests, shared early-warning surveillance for unusual outbreaks, and regular joint training exercises simulating bioweapon attacks. We routinely exercise for missile defense or cyber defense; we should be doing the same for pathogen defense. A centralized biosurveillance network across the alliance, as some experts have suggested, would allow rapid communication of any biological incident. If Poland detects a suspicious anthrax cluster, it should instantly alert all allies and initiate a coordinated response.

- Fix Infrastructure Gaps

Europe, in particular, needs to invest in more high-containment labs and training in its eastern and southern flanks. Countries like the Baltic states, Bulgaria, Romania – many have no BSL-4 lab (the highest biosafety level) at all, and limited BSL-3 capacity. This not only hampers their ability to identify and handle dangerous pathogens, but also presents a strategic vulnerability. NATO could fund regional BSL-3/4 laboratories or mobile lab units, coupled with training programs to grow local expertise.

- Regulate Dual-Use Technologies

We should use the same AI and biotech advances for defense: rapid pathogen sequencing, AI-driven drug discovery for antivirals, drones for aerosol detection, etc. If AI can hypothetically design a pathogen, AI can also help predict emerging threats or model effective treatments in record time. Governments should invest in these innovations. At the same time, there must be regulations on the dual-use side. The international community ought to establish guidelines for gene synthesis companies to screen orders (so no one can just order smallpox DNA easily) and for publishing genomic research that could be misused.

An idea floated by some is to require licenses or background checks for working with certain high-risk gene sequences, analogous to how radioactive materials are monitored. An oversight framework for AI in bio – for instance, a global database of AI models that could be repurposed for toxin or pathogen design, would be useful, as we’d know who is working on what. It’s tricky, but we need creative measures like we did in the nuclear field.

We also need a culture of responsible innovation, where researchers recognize the dual-use potential of their work and build in safeguards. It’s analogous to how cybersecurity became an expected consideration in IT development; biosecurity should be a standard consideration in biotech R&D. This can be advanced by including bioethics and security modules in university curricula and by offering grants for work on detection, diagnostics, and countermeasure platforms.

There’s also room for creative initiatives – for example, “bio-defense hackathons” or challenges to design better biosensors, much like the X-Prize competitions. With the kind of talent and technology available in open societies, we should aim to out-innovate the threats. If adversaries are plotting the next bioweapon, let’s be a step ahead with the next breakthrough in rapid pathogen neutralization.

- Strengthen Global Governance and Norms

The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC), while symbolically important, lacks enforcement. Western democracies must lead in revamping the BWC, advocating for verification mechanisms, and expanding its scope to cover synthetic biology and AI. Biosafety and biosecurity have to become a global effort. Building trust is tough in today’s geopolitical climate, but small steps like voluntary peer reviews of biodefense labs or inviting observers to biodefense exercises could help. We should also strengthen the global disease surveillance networks (like WHO’s Epidemic Intelligence), and ensure that when one country detects something strange, others react and offer help rather than remain silent.

- Strengthen Public-Private Partnerships

They are crucial: many pharmaceutical and tech companies have resources that governments lack. Integrating them into preparedness plans (while maintaining appropriate oversight) can accelerate innovation. For instance, leveraging mRNA vaccine technology – a triumph from COVID – to have “vaccine libraries” ready for known high-threat agents like anthrax, Ebola, or engineered flu. Stockpiling rapid diagnostics and broad-spectrum antivirals is also key.

- Build Whole-of-Society Resilience

Resilience isn’t just labs and vaccines – it’s also public trust and communication. Governments must invest in effective risk communication. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how disinformation can cripple public health responses. In a future bioweapons scenario, panic and mistrust could be as deadly as the pathogen itself. Proactive public education, “prebunking” misinformation, and rapid response coordination with media platforms should all be components of national security strategies.

- Treat Biodefense as Core Defense Policy

Biodefense must receive the same strategic weight as missile defense or counterterrorism. Every major government and alliance needs a dedicated biodefense strategy, adequate budgets, and regular high-level attention. No more neglect. The West needs an “Apollo Program” for biodefense—a multinational, well-resourced effort to close the dangerous gaps exposed by COVID-19. If adversaries believe we can detect, respond to, and recover from bioweapons effectively, we strengthen deterrence by denial. If we remain unprepared, we invite risk.

Conclusions

We must stay a step ahead. History shows that humanity often reacts to disasters rather than preventing them. But we don’t have to be fatalistic. We know the danger is there, growing in shadows. We also have the knowledge and tools, if we choose to use them wisely, to mitigate this danger. Western nations, together with global partners, can significantly reduce the bioweapons threat by acting now with foresight and unity.

The stakes cannot be overstated. A large-scale biological attack could transform life overnight – it’s a prospect none of us wants to see realized. The time to bolster our defenses was yesterday, but failing that, it must be today. Strengthening international norms, investing in preparedness, embracing new tech for good, and guarding against its misuse – these are the pillars of protecting our world from biological warfare. The COVID-19 tragedy taught us just how interdependent and fragile our modern societies are in the face of microscopic threats. We ignore that lesson at our peril. Let’s act with the urgency and commitment this challenge demands, so that future generations look back and say we were ready, and we prevailed.

Disclaimer: To explore the escalating threat of biological weapons and vulnerabilities in Western preparedness, three experts from the Bioshield 2.0 team engage in a roundtable discussion. Igor Arbatov, Olek Suchodolski, and Valentyn Trofimenko share their insights on the current landscape of bioweapon risks, lessons from COVID-19, technological game-changers, and what NATO and the EU must do to strengthen defenses. Daryna Sydorenko, Director of Research in the Transatlantic Dialogue Center (Ukraine), organized and set the format for the meeting. The conversation is edited for clarity and length.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations with which the authors may be associated.