3 MB

Key Takeaways

- The Ukrainian American diaspora is a large and active community that serves as a powerful source of political influence and soft power that significantly strengthens Ukraine’s position in the United States.

- Over its history, the diaspora has shaped politics both in the United States and in Ukraine. It still uses many tools at its disposal to support Ukraine during its war with Russia.

- Diaspora political influence works best through multi-level advocacy, which combines grassroots activism, state-level resolutions, federal lobbying, PACs, and caucus engagement, creating maximum impact.

- Stronger cooperation among diaspora organizations and cross-diaspora alliances is essential for the evolution of diaspora advocacy, as it greatly magnifies influence on the United States policy.

- The diaspora faces an increasingly stark organizational, generational, and political divide. This comes from both the increasingly complicated relationship between the United States and Ukraine, as well as the political polarization in the United States.

- Sustaining the diaspora participation post-war will be a significant challenge for the diaspora organizations.

Recommendations

Since the start of the war in 2014, the American Ukrainian diaspora has established itself as one of the most active and politically influential ethnic communities in the United States. To sustain and expand its influence in a complicated political environment, a structured, multi-level approach is needed, combining grassroots mobilization, state-level engagement, and federal lobbying under a unified diaspora-wide strategy. The goal is to ensure that support for Ukraine remains bipartisan, sustainable, and deeply rooted within American society.

Targeting Different Levels of U.S. Politics

For the diaspora advocacy to utilize its full potential, it is absolutely crucial to engage with all layers of the American political system, federal, state, and local, simultaneously, maintaining consistent coordination and shared messaging.

At the federal level, umbrella organizations should continue to play the leading role in lobbying the U.S. Congress and the Executive Branch. Expanding and strengthening the Congressional Ukraine Caucus and the Senate Ukraine Caucus remains an important objective, alongside cultivating relationships with the State Department, Department of Defense, the United States military, and relevant committees. These efforts should focus on maintaining a bipartisan commitment to Ukraine.

At the state and regional levels, the national and local organizations should prioritize outreach to governors, state assemblies, and local media outlets. At the same time, they should promote Ukrainian American participation in state and municipal politics, supporting candidates, forming local caucuses, and ensuring Ukrainian issues are visible in state political debates.

At the grassroots level, the diaspora should strengthen the community itself through voter mobilization, civic education, and local partnerships. Churches, youth organizations, and cultural centers play a critical role in shaping civic identity and encouraging political participation. Coordinated campaigns such as “Your Vote, Ukraine’s Voice” could be used to increase voter turnout and civic engagement among Ukrainian Americans.

Focusing on Diaspora Centers and Local Elections

The American Ukrainian community has shown itself to be a capable political force in Washington and in some states. However, it has not developed a uniform strategy or structure in local politics. Local organizations could consolidate into more effective local groupings to have the resources to enact change. To build sustainable influence, Ukrainian Americans would benefit from focusing on key diaspora hubs such as Illinois, Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, California, Ohio, Michigan, and Washington. These areas have the potential to influence congressional and state elections. Building local political networks would give a much more solid foundation of support for Ukrainians in higher levels of Government.

Local campaigns should focus on:

- Encouraging diaspora members to vote and volunteer in local elections.

- Organizing candidate forums and voter education events.

- Working with city councils to strengthen the Ukrainian community.

- Supporting Ukrainian Americans to run for municipal and state office.

Such activities not only strengthen the diaspora’s visibility but also create political allies who understand Ukrainian issues firsthand.

Enhancing Cooperation with Other Diasporas

Many influential diaspora organizations have shown willingness to support the effort of the Ukrainian diaspora. Partnerships with other Central and Eastern European communities are essential to maintaining a broad and credible pro-democracy coalition in Washington. Joint advocacy campaigns would amplify Ukrainian positions by presenting them as part of a larger regional struggle for sovereignty and democracy. If the war in Ukraine is shown to be a part of a larger global security issue, this could help to engage more voters and more politicians in the United States, giving Ukraine more leverage in the 2026 elections. Strengthening cooperation with Finnish, Polish, and Baltic groups also reinforces transatlantic credibility and demonstrates that support for Ukraine is part of a consistent U.S. foreign policy toward Eastern Europe.

Expanding Political Action Tools

The diaspora would benefit from a higher degree of coordination and cooperation with institutions and civil organizations in Ukraine. This would mean a higher degree of interdependence in aid, getting input from Ukrainian aid organizations about what aid is needed the most, and relaying that to local organizations in the U.S. In cooperation with the Ukrainian government, the diaspora should act as an intermediary, helping to connect Ukrainian politicians with American ones, both in Washington and on the local level. This would ensure that diaspora messaging aligns with Ukraine’s foreign policy priorities while maintaining the diaspora’s independence as an American civic actor.

Introduction

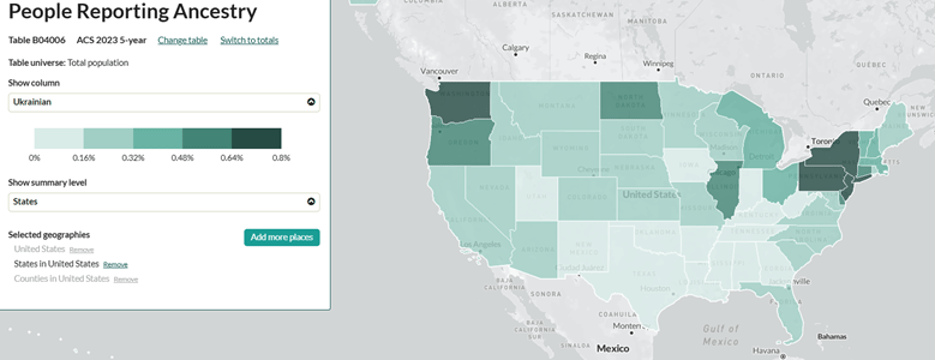

While the Ukrainian diaspora does not constitute one of the major ethnicities in the United States, the impact of 1.2 million Americans of Ukrainian ancestry on the development of both the United States and Ukraine cannot be discounted. Communities and organizations of Ukrainians who arrived in the first wave during the 1880-1914 period from Austro-Hungary became some of the first active voices abroad advocating for Ukrainian independence. Since the 1920s, the Ukrainian community has been one of the most vocally anti-communist ethnic groups, shaping the United States’ response to the Soviet Union in the interwar period as well as during the Cold War. The collapse of the Soviet Union led to an increase in emigration into the United States but also meant a decrease in Ukrainian political cohesion until the Euromaidan protests in 2013, which rejuvenated the American Ukrainian community’s activism. Currently, Americans of full or partial Ukrainian ancestry make up around 0.4% of the population of the United States, with the biggest communities in the states of New York, California, Pennsylvania, and Washington.

The Ukrainian diaspora has been exerting considerable pressure on the United States politics through political organizations, but has been less likely to use elections as a way to pressure the U.S. foreign policy in a more pro-Ukrainian direction. The United States has a long history of different diaspora groups, such as Israeli American and Cuban American communities, being able to influence foreign policy through voting habits and lobbying.

The objective of this paper is to look into the historical and current effects of the Ukrainian diaspora on the formulation of the United States’ foreign policy. It will also look into the political effects of the Russo-Ukrainian War on the United States, brought on by the Ukrainian diaspora. Moreover, it seeks to find recommendations for diaspora organizations, U.S. policymakers, and Ukraine to help them engage the Ukrainian Americans and work in American politics.

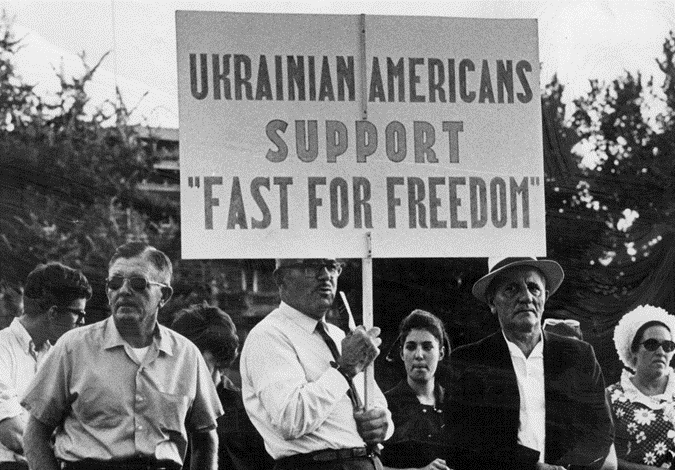

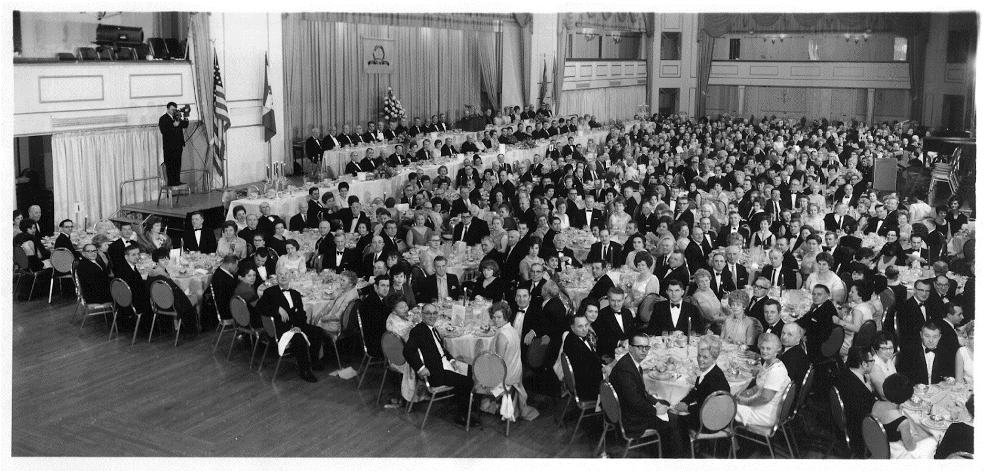

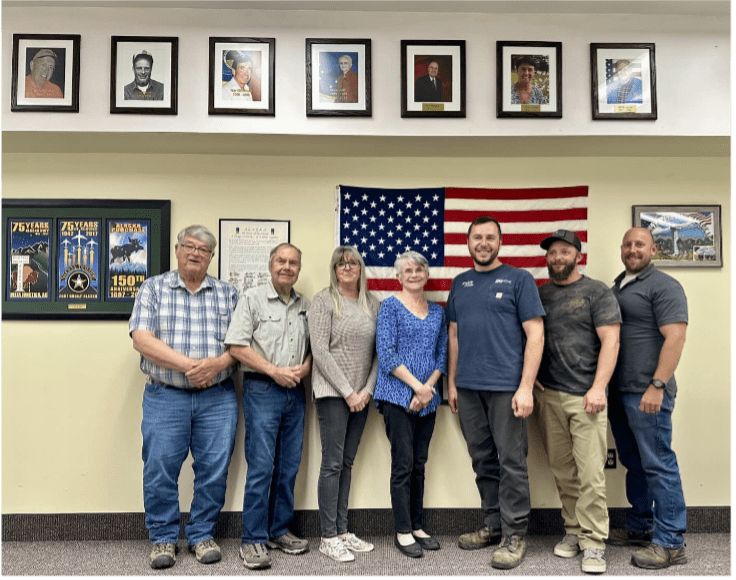

Courtesy of Father Tim Tomson and St. Mary’s Ukrainian Church in McKees Rocks

Historical Waves of Ukrainian Immigration

Pre-independence waves of Ukrainian immigration

The first known Ukrainians arrived in the United States in the 17th century, with Ivan Bohdan, a companion of John Smith, considered to be the first Ukrainian in the New World; however, a large-scale immigration of Ukrainians only began in the 1880s. This first wave of immigration, before the beginning of World War I, saw around 250,000-350,000 Ukrainians from Austro-Hungary settle in America. These Western Ukrainian immigrants were considered to be Ruthenians or Rusyns. In fact, the Hungarian-dominated “Chro-Rusyn” Catholic church, the Russian-dominated Orthodox church, and the Ukrainian Catholic church competed in the United States for the ethnic loyalties of the first wave immigrants, with around 40% becoming the Ukrainian community. This first wave was mostly politically inactive, instead creating a distinct social community for Ukrainian culture in America and developing an independent Ukrainian identity.

The beginning of World War I inspired the Ukrainian diaspora, similarly to the other Eastern European diasporas, to push for independence or autonomy of Ukraine. The establishment of the Ukrainian People’s Republic in 1917, showed that there was the will for independent Ukraine and that quickly gained the support of the Ukrainian community in the U.S. While the Ukrainian diaspora had some success in raising the “Ukrainian question” in the U.S. politics, unlike Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Finland and Poland, they ultimately were unable to sustain and expand the support from American politicians. This failure can, however, be chalked up to the developments in Ukraine, more so than to the actions of the diaspora. Specifically, the support of the German Empire, the inability to hold onto its territory, and pogroms in western Ukraine largely poisoned the Ukrainian aspirations of recognition.

The second wave of immigration of the interwar period saw only between 11,000 y 40,000 Ukrainians moving to the United States. While the center of gravity of the Ukrainian diaspora’s political activity was in Europe, the era was characterized by increased internal politicization and especially political polarization into far-right and far-left organizations.

The third wave of Ukrainian immigration into the United States came on the heels of World War II. During the war, around 2,3 million Ukrainians left or were forced to leave the Ukrainian territory. Between 80,000 – 100,000 of these people, mostly connected with the national movement and as such unwelcome in the Soviet Union, arrived in the US between 1946 and 1959. These politically active “new” immigrants came into conflict with the political views of established “old” immigrants and often pushed them out of the diaspora political organizations. As the Cold War progressed, the Ukrainian diaspora was able to gain more influence in American politics.

Cold War politics

While World War I saw the first organized effort of the Ukrainian diaspora to influence U.S. politics, it wasn’t until the arrival of Ukrainian immigrants during the 1940s and 1950s when they became an organized political force. It was largely thanks to the UCCA’s efforts that this wave of immigration became possible. The organization successfully campaigned for the Displaced Persons Act of 1948 and founded the United Ukrainian American Relief Committee (UUARC). This was quite an achievement considering that the American public at that time viewed the Ukrainian refugees as little more than nazi collaborators.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the most important political victories for the Ukrainian diaspora were the passage of the 1959 Captive Nations Resolution, spearheaded by the president of UCCA, Dr. Lev Dobriansky, and the erection of the Taras Shevchenko monument in Washington. The 1970s and 1980s saw important Ukrainian diaspora human rights campaigns for the United States to demand the release of the Ukrainian Helsinki Group and to recognize the Holodomor.

In 1974, the U.S. also enacted the Jackson–Vanik Amendment, which tied trade relations to emigration restrictions for religious minorities. While largely irrelevant for the diaspora at the time, this amendment and the subsequent Lautenberg Amendment (1990) became highly significant during the collapse of the Soviet Union, when many Ukrainians used them to immigrate to the United States.

Post-1991

While the Ukrainian diaspora was seen as an important actor in the United States’ rivalry with the Soviet Union, in the end, the independence of Ukraine came as a complete surprise for almost everyone. The collapse of the Soviet Union and subsequent economic trouble led to the fourth wave of Ukrainian immigration between 1991 and 2014. For the first time, immigration into the United States included people from all parts of Ukraine. This wave was composed almost entirely of economic emigrants and numbered between 200,000–350,000. Before the start of the Russo-Ukrainian war, this fourth wave accounted for around 20% of the total diaspora, with the most active part being more educated and having closer ties to Ukraine. These Ukrainian families now represent the most politically powerful part of the diaspora.

The fall of the Soviet Union opened a door for the diaspora community to participate in the politics of Ukraine. This was first done by providing monetary support to the Ukrainian popular front, the Popular Movement of Ukraine for Reconstruction, through the Friends of Rukh organization, as well as through lobbying efforts for recognizing Ukraine’s independence in Canada and in the United States. In the 1990s, two Ukrainian political parties, both of which represented the legacy of third wave immigrants connected with the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), had significant backing from the Ukrainian diaspora. Since World War II, the third wave of Ukrainians had been divided within the OUN by their loyalties to Bandera and Melnyk factions. This divide continued even after the proclamation of Ukraine’s independence. The Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists (KUN) was founded by immigrants of the Bandera OUN faction, while the Melnyk OUN faction supported the activities of the Ukrainian Republican Party (URP). In the end, both parties experienced little success in Ukrainian politics. By the 2000s, the political and social organization of the diaspora had integrated some of the fourth wave immigrants, but also lost most of its political focus.

The identity of third and fourth-wave immigrants often clashes. For example, the more political third wave is often dismissive towards Russian-speaking newcomers from Ukraine, considering them less Ukrainian as they prefer the Russian language. Third wave Ukrainians are also much more connected with formal Ukrainian cultural and political organizations. Fourth wave Ukrainians are mostly organized in non-formal communities, such as social clubs and online groups.

This could be a legacy of the pre-independence community or signal the cultural rift between different waves. This is especially true in connection with supporting the Maidan movement and Ukraine in the Russo-Ukrainian war. For the older waves, the support comes mainly through donating to older and well-established diaspora organizations, while the new waves support Ukraine mainly in grassroots actions, such as protests and collection drives, based around social networks. Even the geographical distribution shows the rift; many old “smalltown” Ukrainian communities in Michigan, Nebraska, and Pennsylvania are losing their historic connection to Ukraine as fourth-wave immigrants mostly move to bigger cities.

Post-2014

The end of 2013 gave rise to many changes in Ukrainian society, and the Ukrainian diaspora was by no means an exception. The occupation of Crimea and the war in the Donbas region led to many Ukrainians escaping those regions, with the United States receiving a renewed inflow of Ukrainian immigrants, with around 10,000 arriving each year. This inflow increased considerably in 2022 with the full-scale Russian invasion and Ukrainian refugee crisis. Overall, this wave numbers over 200,000 people, a large part of whom arrived in 2022.

Despite the majority of the fifth wave migrants being from eastern Ukraine, in their motivations and cultural aspects, they often have more in common with the third wave Ukrainians than with those who arrived in the 1990s. Being forced from Ukraine due to the Russian invasion closely mirrors the experience of the third wave, with the fifth wave being more politically active than those of the fourth wave. For them, the hope is mostly to return to Ukraine after the war. In addition, among the fifth wave Ukrainians, 60% prefer speaking Ukrainian day-to-day compared to 40% of the fourth wave Ukrainians. The fifth wave is also better educated compared to the previous diaspora members. Overall, this new wave of Ukrainians represents a more politically motivated and culturally conscious segment, but it’s still early to say if their political impact will remain or if it’s a short-term effect of the current circumstances.

Political Mobilization of the Diaspora

Organizational infrastructure

Since the very first days of the Ukrainian diaspora, the Ukrainian National Association (UNA), established in 1894, has been the most significant organization of Ukrainians in the United States. At its peak in the 1960s and 1970s, it had over 85,000 members. Current numbers are significantly lower, but it still holds a leadership position in the UCCA and, through that, in the entire diaspora.

Umbrella organizations

First significant cooperation efforts between American Ukrainian organizations appeared during World War I, when in 1915 the first congress of Ukrainians in America convened and established a short-lived Federation of Ukrainians in the United States. Currently, there are three main American Ukrainian umbrella organizations:

- The Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (UCCA) – Established in 1940, historically most influential, with around 30 of the biggest organizations.

- Ukrainian American Coordinating Council (UACC) – Established in 1965, it went on to represent mostly the diaspora organization on the West Coast, having the support of the newer wave of emigrants.

- American Coalition for Ukraine (ACU) – Founded in 2022 with more than 100 member organizations.

Religious institutions

Religious organizations have been one of the most influential forces in the Ukrainian diaspora. This was especially true before independence, when the church served a role of a semi-political force rallying the Ukrainian diaspora against the atheistic Soviet Union. Many diaspora members immigrated specifically due to religious persecution, connecting their national and religious identity. The Ukrainian immigrant groups were centered around churches, which created their own schools and community organizations and carried forth the cultural identity and language. The first immigrant waves from Western Ukraine were mainly Eastern Catholic and Orthodox, but more recent waves have favored the evangelical Protestants due to the Lautenberg Amendment. Almost all religious members of the Ukrainian diaspora lean considerably to the right, with earlier generations influenced largely by the Cold War legacy. Fourth-wave evangelical Christian groups are an important part of the Christian right, supporting the MAGA movement while being less engaged with Ukrainian culture or national identity. The creation of several Ukrainian Christian churches by various Christian denominations in Washington State in 2024 shows that political cooperation between diaspora religious organizations can be a significant political force. Currently, the biggest Ukrainian diaspora religious organizations are:

- Ukrainian Catholic Archeparchy of Philadelphia – In 2023, it had around 12,000 members, compared to roughly 500,000 a century ago.

- Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the USA – In 2020, it had around 15,000 members and 89 parishes.

Student associations and educational institutions

Historically, the Ukrainian diaspora student unions in the United States have acted independently, with the first country-wide organization established in 1953, after the Central Union of Ukrainian Students (TseSUS) moved its head office there. The Federation of Ukrainian Student Organizations of America (SUSTA) first united young people from 50 different universities. After going defunct in the 2010s, it was revived in 2022 and contains 13 student associations from across the country. However, this represents only a minuscule part of the total number of such organizations.

Ukrainian American research and education institutions are considerably better organized and impactful. There are many significant research organizations with a focus on Ukraine:

- Ukrainian Research Institute in Harvard University (HURI) – Institute created in 1973 by SUSTA’s initiative and with funding from the Ukrainian diaspora.

- The Shevchenko Scientific Society – Scholarly institution established in the state of New York in 1948.

- The Ukrainian Institute of America – An institute promoting Ukrainian educational, professional, and social activities, established in 1948.

- The American Association for Ukrainian Studies (AAUS) – Aneducational organization bringing together researchers of Ukraine. Founded in 1989.

Humanitarian NGOs

With the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War, the Ukrainian diaspora-led humanitarian NGOs have become the most significant community groups. It was those organizations that, in September 2022, launched the American Coalition for Ukraine (ACU), which now has over 100 U.S.-based organizations focusing on supporting Ukraine. It has been the ACU that has taken the leading role in political action of the Ukrainian diaspora, using advocacy campaigns, demonstrations, fundraisers, lobbying, and other events to amplify their impact. The main founders of the ACU include:

- Razom for Ukraine – Founded in 2014. Represents one of the largest and most impactful humanitarian diaspora NGOs with strong advocacy power and a humanitarian aid focus. As of October 2025, they have raised and donated around 140 million dollars.

- United Help Ukraine (UHU) – Founded in 2014 by Washington D.C.-based protestors. As of October 2025, they have donated over 80 million dollars, focusing on medical and military aid.

- Nova Ukraine – Founded in February 2014 in California, with a focus on delivering aid to refugees. Nova Ukraine has sent over 130 million dollars’ worth of aid to Ukraine, helping over 10 million people.

- Ukrainian National Women’s League of America (UNWLA) – The Ukrainian National Women’s League of America was established in 1925. Unlike other founders of ACU, the UNWLA is also an important cultural and educational organization playing a part in the Ukrainian diaspora for a century.

- Ukrainian American Coordinating Council (UACC) – Main umbrella organization of the West Coast diaspora community, founded in the 1960s.

Media

Ukrainian diaspora media have a long history in the United States. The Svoboda newspaper, published since 1893 by the UNA, is the oldest Ukrainian-language newspaper in the world. Svoboda and its English language counterpart, The Ukrainian Weekly, have been the backbone of diaspora media in the U.S. While the traditional Ukrainian media in the United States has been disappearing, the war has stimulated a renaissance of Ukrainian media. With increased political and humanitarian mobilization, the diaspora’s focus has shifted to the online presence of NGOs and activist groups.

Recently, the political mobilization of the Ukrainian diaspora has seen a shift towards decentralized digital advocacy. While lacking formal organizational structure, Ukrainian and Ukrainian-American bloggers and influencers have become a significant force in shaping U.S. public opinion. These individuals produce English-language content across major social media platforms (YouTube, TikTok, Instagram). Their function is two-fold: they translate complex Ukrainian narratives and geopolitical realities into accessible formats for Western audiences, and they serve as direct conduits for grassroots fundraising and political calls to action. Their wide reach allows them to engage millions of Americans, fostering empathy and sustaining political support for Ukraine’s struggle against Russia, particularly among younger demographics that traditional diaspora media channels may not reach.

Lobbying in Washington, D.C.

Ukraine Caucuses

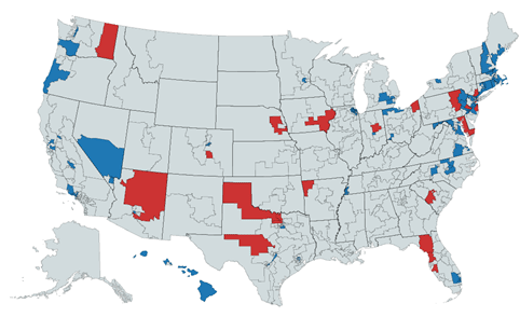

upporters of Ukraine have established caucuses in both the House and the Senate. In the House of Representatives, the Congressional Ukraine Caucus was established in 1997 and as of June 2022 had 100 members – 21 republicans and 79 democrats. This caucus has been behind some of the most significant legislative initiatives concerning support to Ukraine since 2014, such as the Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014.

The Ukraine caucus in the Senate is significantly younger and was created in February 2015. The Senate’s caucuses are more informal. Their non-official members include 17 members, 9 republicans and 8 democrats.

It must be noted, however, that even for members of Ukrainian caucuses, the support is not always guaranteed. Many hardline Republicans have taken on an increasingly negative view toward Ukraine, brought on by opposition to the Biden administration. For example, Gus Bilirakis, the House member, initially supported funding to Ukraine but has since rallied against it. Senator John Barrasso, one of the leaders of the Republican Party, broke ranks as the only member of the GOP leadership who voted against the aid packages for Ukraine.

One of the most significant agencies working with Ukraine and the Ukrainian diaspora has been the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE), a.k.a. the Helsinki Commission. The creation of this agency in 1975 to monitor the Helsinki Accords provided a rallying point for American Ukrainian activists during the Cold War. In fact, most of their lobbying during the 1970s and 1980s focused on the Helsinki Accords and their implementation in Soviet Ukraine. Since 2014, the Commission has held numerous hearings and released briefings about Ukraine, often co-operating with the Ukrainian diaspora. The Helsinki Commission offers a direct and issue-focused channel to the U.S. government.

Ukrainian American diaspora’s work on supporting imprisoned dissidents in Soviet Ukraine in the 1970s showed them clearly the importance of their presence in Washington, D.C. For this purpose, in November 1977, the UCCA established the Ukrainian National Information Service (UNIS). This office, together with the U.S.-Ukraine Foundation (USUF), acts as the main communication middleman between the Ukrainian caucuses, the Helsinki Commission, and the diaspora.

The US Helsinki Commission at a hearing about Baltic Sea security in July 2019.Source: Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe, United States Congress

Political Action Committees

Currently, the only functioning Political Action Committee (PAC) advocating solely for Ukraine is the American Ukraine PAC, created in March 2024 by Jed Sunden, the founder of Kyiv Post. This PAC has raised around 156,000 dollars, mostly from Jed Sunden himself and the Ukrainian American diaspora, and spent around 136,000 dollars. It has been supported by the most visible pro-Ukrainian politicians country-wide, on both sides of the aisle, through earmarked contributions. There have been other attempts to create PACs by the Ukrainian diaspora, but they were unsuccessful.

Lobbying activities

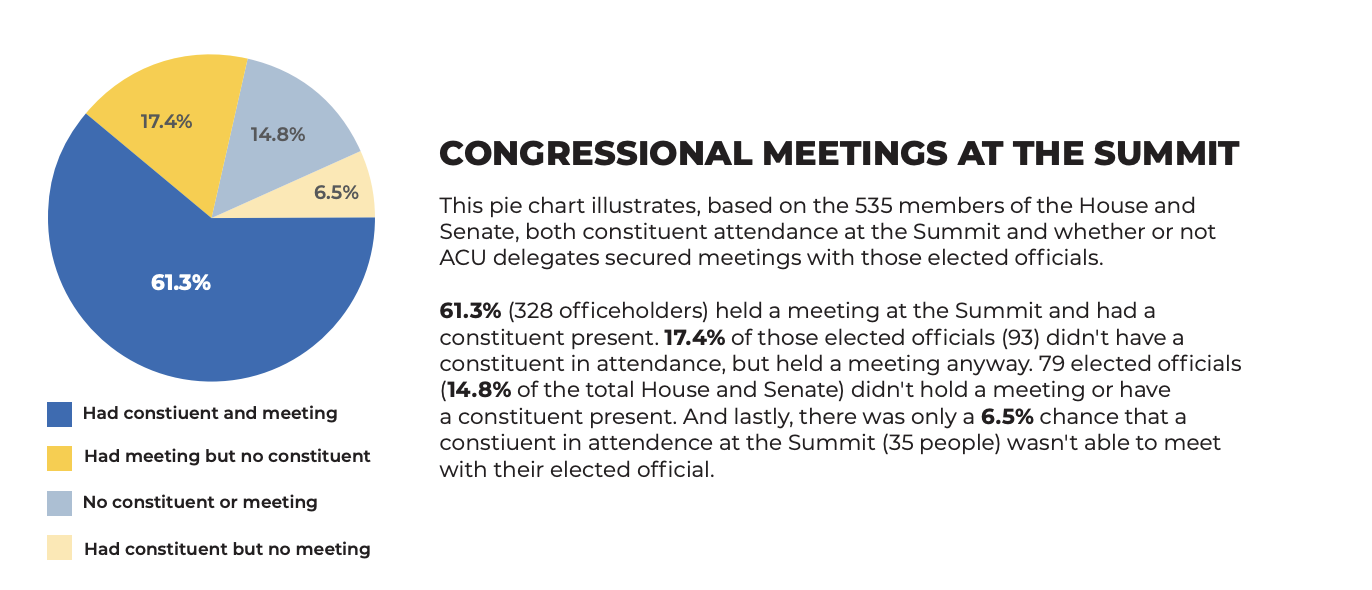

Since 2022, the ACU has organized a biannual community coordination event, the Ukraine Action Summit, in Washington, D.C. This event is not only an important tool for forming a coordinated advocacy effort, but it also serves as a primary event for lobbying officials of the U.S. government. Its impact is hard to overstate. During the sixth Ukraine Action Summit in spring 2025, more than 600 delegates met with more than three-quarters of the Senate and House to advocate for tightening sanctions on Russia. Data from previous summits has shown that usually those summits generate a tangible number of new co-sponsors for the bills they are advocating for.

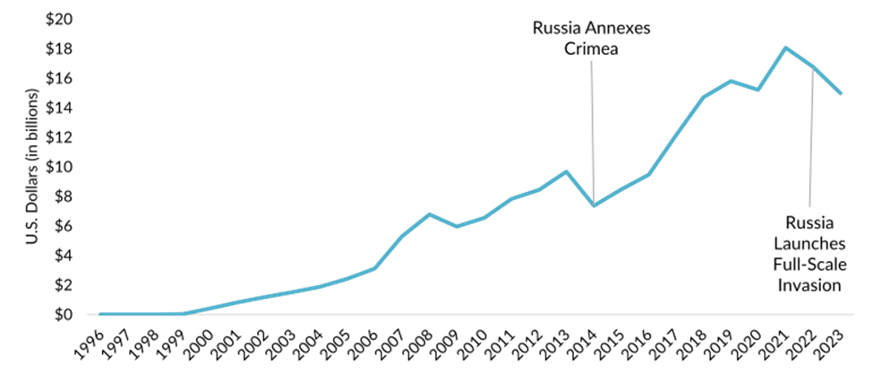

At the same time, the cause of Ukraine has attracted a significant number of Washington lobbyists to its side. Until 2022, the pro-Ukrainian lobby in the United States was fighting an uphill battle. In 2021, for example, the Russian clients paid over 42 million dollars to lobbying firms in Washington, which was 40 million dollars more than Ukrainians, achieving, however, much less success than Ukrainian efforts. The start of the war saw the Russian lobby all but disappear due to sanctions, while the Ukrainian cause has been adopted “pro bono” by many lobbying firms. Even as the biggest lobbying firms in Washington, such as Hogan Lovells, BGR, and Mercury, offer their services to the Ukrainian government, the diaspora lobbying still has a part to play. Razom for Ukraine has paid close to half a million dollars to lobbying firms since the start of the war.

Post-Maidan

Obama’s Administration

Since 2014, the “Ukrainian question” has become one of the most significant priorities of U.S. foreign policy. This has given the Ukrainian diaspora an unprecedented voice in the United States’ politics. During the Obama administration, up until 2017, this included the passage of bills such as:

- Support for the Sovereignty, Integrity, Democracy, and Economic Stability of Ukraine Act of 2014

- Ukraine Freedom Support Act of 2014

Victoria Nuland, the Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs, well-known for her pro-Ukrainian stance, is considered the main politician shaping the United States’ response during Obama’s presidency. Multiple American Ukrainian diaspora members had their hand in shaping the response of the Obama administration, including a pro-Ukrainian activist in the Democratic National Committee, Alexandra Chalupa, head of the Ukrainian Service at the Voice of America, Myroslava Gongadze, and the President of the UCCA, Tamara Gallo Olexy. Nonetheless, President Obama decided to follow a less confrontational policy, being hesitant to provide military equipment to Ukraine despite calls by the House and Senate. Some have considered this decision to have led to the widening of the conflict.

Trump’s First Administration

The Ukrainian diaspora’s relationship with the Trump administration was strained even before he took office. Paul Manafort, the chair of Trump’s presidential campaign, was investigated by Alexandra Chalupa for his alleged ties to the Russian government and Viktor Yanukovych before 2014. Even as the Ukrainian government was not involved in this, the scandal considerably damaged the relations between the two countries. Despite President Trump’s sometimes critical stance toward Ukraine, his administration actually increased support for the country, passing several important pieces of legislation, including:

- Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) in 2017.

- Javelin missile sales approval at the end of 2017.

- National Defense Authorization Acts of 2018, 2019, 2020, and 2021.

Even in this difficult situation, the Ukrainian diaspora was able to maintain broad support from the House and Senate, as can be seen from the almost unanimous support for the CAATSA Act in July 2017. Relations were further complicated by the Ukraine aid freeze and the following Trump–Ukraine scandal in 2019.

Biden’s Administration

In the first months of his presidency, Biden mostly followed the policy in place since 2014. However, the increased military presence of Russian troops on the Ukrainian border throughout 2021 led to increased aid to Ukraine. The invasion in February 2022 brought on an unprecedented change to both US-Ukraine relations and to the Ukrainian diaspora in the United States. It radically expanded the size, visibility, and political coordination within the Ukrainian American diaspora. This was especially evident through the emergence of the American Coalition for Ukraine (ACU), which became the primary coordination platform for the Ukrainian diaspora in the U.S. Many key pieces of legislation were pushed through in large part due to the support and advocacy of the diaspora, such as:

- Ukraine Democracy Defense Lend-Lease Act of 2022

- Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Acts (2022–2024)

- Rebuilding Economic Prosperity and Opportunity for Ukrainians Act of 2024

Despite many successes of the Ukrainian diaspora in securing the passage of pro-Ukrainian legislation, the support turned out to be insufficient.

Influence on Foreign Policy

The question of Eastern Europe and Russia was one of the main foreign policy problems for the U.S. throughout the Cold War. As the U.S. and Soviet Union became increasingly antagonistic in the second half of the 1940s and in the 1950s, this presented a possibility for the “captive nations” to garner support from the government and influence the views of U.S. foreign policy. For the Ukrainian diaspora, unlike the Baltic, this was the fight not only for independence but also for the very notion of the possibility of Ukraine’s existence. During the Cold War, the Ukrainian diaspora in the U.S. had to establish the understanding that Ukraine was not merely a region of Russia, but as a distinct nation deserving of independence, something that they were unable to do during the interwar years.

The Ukrainian diaspora was able to establish the recognition of Ukrainians as a distinct nationality through many campaigns. However, as was evident in the speeches of Margaret Thatcher y George H. W. Bush in 1990 and 1991, respectively, unlike with the Baltic states, Ukrainian independence was not supported either by the U.S. or the United Kingdom. The recognition of Ukrainian independence in December 1991 was, thus, an acceptance of a new reality, brought on by the pressure of voters of Eastern European diasporas and the rapid disintegration of the Soviet Union.

After the independence of Ukraine was proclaimed, the diaspora’s focus shifted to enhancing relations between Ukraine and the U.S. as well as garnering economic support for the country. To this extent, it once again had to contend with the “Russia-first” approach of the U.S. Eastern European policy. In the first years of Ukrainian independence, the relations between these countries were mainly concerned with the nuclear weapons issue, which was addressed by the Nunn-Lugar Act and later the Budapest Memorandum. These relations later deepened, in large part thanks to the establishment of the Congressional Ukrainian Caucus in 1997. The diaspora was noticeably activated during the Maidan protests and in the following Russo-Ukrainian War. It aimed to change the image of Russia in U.S. politics from a “strategic partner” to an aggressive revisionist power and to pressure the U.S. to increase aid to Ukraine. The diaspora has largely played a role on the grassroots level, changing public opinion while also engaging the higher levels of government through diaspora organizations and NGOs.

Role in U.S. Domestic Politics

The “Ukrainian question” in American politics

For decades after the end of the Cold War, U.S. support for Ukraine was largely bipartisan, with overlap with the internal political issues the United States faced. Whether this was due to the widespread support for the newly independent nation or just due to the relative unimportance of Ukraine, it is the United States politics that could be debated, but whatever the case may be, this meant that the support for Ukraine, for example, in caucuses was split almost completely evenly.

Revolution of Dignity and Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 pushed Ukraine to the forefront of foreign policy for the United States, and so the seepage of the “Ukrainian question” into American internal politics before the tumultuous 2016 elections was unavoidable. Many Russian-born narratives emerged in the political fringes in the United States, for example, the Nuland-Pyatt call was used by some in the American far-left and far-right to push a narrative of a CIA-backed “Color Revolution”, a widespread conspiracy theory in Russia since 2012. In the lead-up to the elections, the Russian government enacted a multilayered campaign to influence and disturb the elections, pushing even more conspiracy theories about Ukraine. This left the American Ukrainian diaspora to fight the effective Russian state-sponsored propaganda machine, something that it was unable to do. This misinformation campaign didn’t reach mainstream politics in the first years of the war, but it did plant the seeds of skepticism that later flourished in the MAGA movement.

It was the lead-up to the 2019 presidential elections that entangled Ukraine and its diaspora firmly in the webs of partisan politics. In the summer of 2019, President Donald Trump allegedly withheld around 400 million dollars in military aid from Ukraine to pressure its government to investigate Hunter Biden’s business dealings in the country. This was most likely based on allegations that Joe Biden had stopped investigations into Burisma, a Ukrainian gas company connected with Hunter Biden. This scandal, based on Ruso conspiracy theories, led to the impeachment inquiry and soured relations between Ukraine and the MAGA movement. Many conspiracy theories that were before unpopular amongst Republicans spread, as the Ukrainian issue became a proxy battleground of the U.S. culture war. The impact of this on the American Ukrainian diaspora has been significant, as it has led to a divided community. For many in the diaspora, the messages of the MAGA movement fit well with their own worldview, and so they dismiss the anti-Ukrainian conspiracy theories of the movement.

This divide doesn’t, however, follow the party lines strictly; during the Cold War, it was the Republican Party that was the fiercest supporter of the Ukrainian diaspora. While the harshest critics of Ukraine, such as Marjorie Taylor Greene and Matt Gaetz, are loud voices in the current Republican Party, the more traditional conservatives, such as Mitch McConnell and Lindsey Graham, still dominate the Senate and the House. Legislation supporting Ukraine has overall had strong support in both chambers of the Government, with funding most often stuck behind the actions of the President or other external considerations.

From Community to Congress

While most of the support for Ukraine comes down to the ideology and interests of American policymakers, there still exists considerable upward pressure from the Ukrainian diaspora and the American population. Even as Ukraine has lost supporters since 2022, especially amongst Republicans, the support is still high with both republicans and democrats. If this backing is maintained, the pressure will keep politicians from abandoning Ukraine. In this “grassroots” level, the Ukrainian diaspora has been vital, as they carry the main weight of promoting Ukraine through rallies and information campaigns. Moreover, the campaigns of the diaspora not only shape public opinion but also show the strength of the over one million-strong Ukrainian American community.

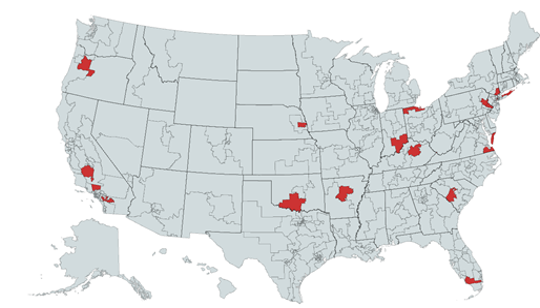

n some municipalities, the Ukrainian community is not only an influence but the main political force. During different waves of immigration to the United States, Ukrainians established many communities, and while most of them have lost their historical Ukrainian roots, some still represent concentrated Ukrainian clusters of influence. Such communities are especially common in the states of Illinois, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Michigan. In Delta Junction, Alaska, Ukrainians make up a significant part of the population, with the mayor, Igor Zaremba, being born in Ukraine. In Parma, the town with the largest population of Ukrainians in Ohio, the local Ukrainian-American community pushed the local officials and businesses to display Ukrainian flags. The city council in Chicago, which has a strong Ukrainian heritage, has introduced multiple resolutions about the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and the Philadelphia City Council debated calling for a no-fly zone in Ukraine in 2022.

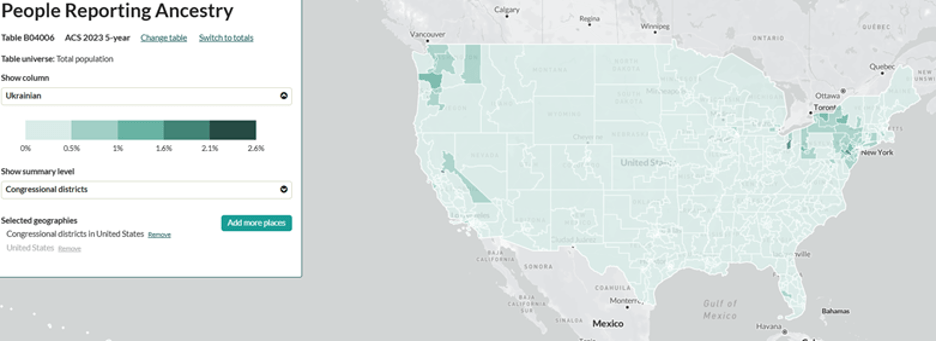

American Ukrainians have concentrated in certain counties, giving them a voice in the elections of the House; nonetheless, diaspora influence is less about numbers and more about visibility. Even in the congressional districts with the highest concentration of Ukrainians, they do not make up more than 2,6% of the total population. The power that the Ukrainian communities have on the district level comes down mostly to the cooperation with other diasporas and the work of community members. Ukrainian community members often serve as local organizers, donors, and volunteers for campaigns, which gives them access to decision-makers and visibility. At the congressional district level, the local Ukrainian American community centers are used as conduits to show the importance of Ukrainian diaspora issues to the politicians in Congress.

On the State level, the Ukrainian diaspora organizations have been able to effectively gather support. Most significant Ukrainian American diasporas are in the states of New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington, with other significant historical communities in Illinois, Connecticut, New Jersey, and California. Despite Ukrainians making up less than 1% of the populations of these states, in some cases, the votes of Ukrainians could have changed the outcome of not only local but even countrywide elections. For example, in the state of Pennsylvania, the Ukrainian diaspora of 120,000 could have swung the state for Harris in 2024.

A big part of diaspora influence comes from diaspora umbrella organizations; for example, the Illinois division of the UCCA has been actively organizing campaigns and protests as well as meeting with state representatives. Campaigning in the state legislature has been a way to garner support outside the federal level as well as to put pressure on the Senate and House. Multiple states recognized the Holodomor man-made famine as genocide in 2017, pushing the U.S. government to do the same in 2018, and many sent help to Ukraine in 2022.

At the federal level, Ukrainian diaspora advocacy is shaped by the national umbrella organizations such as the UCCA and ACU, which work with the Ukrainian caucuses in the Senate and House. Even at this level, the local organizations are important as the most pro-Ukrainian voices mostly come from states that have a well-developed diaspora community, which has influenced the politics at the lower levels.

Tactics (Holodomor campaign between 2014-2018)

The recognition of the Holodomor as a genocide stands as one of the clearest examples of how the American Ukrainian diaspora has been able to push change in the United States politics through using different levels of political engagement.

The Holodomor has always been central to the Ukrainian diaspora, even in 1933, the Ukrainians organized demonstrations and were able to raise the issue in the Congress. It was the campaigns after 2014, in the lead-up to the 85th anniversary of Holodomor, that finally led to the nationwide recognition of Holodomor as a genocide in March of 2018. This success can be explained by both the increased visibility of the Ukrainian diaspora and a long-term step-by-step mobilization from the community to Congress.

At the foundation of advocacy were grassroots initiatives. Ukrainian churches, cultural organizations, and youth groups have for decades organized public commemorations, protests, and media campaigns to educate Americans about the Holodomor. Through exhibitions, events, and articles in regional newspapers, they framed the famine as both a Ukrainian tragedy and a universal warning against totalitarianism. This was incredibly important to create civic visibility and generate the knowledge and moral legitimacy needed for further lobbying. Such events included many local “Remembrance” days over the years and especially the events surrounding the unveiling of the memorial to the victims of Holodomor in Washington, D.C., in 2015, which was spearheaded by the U.S. Holodomor Committee.

While organizing community events, the diaspora was actively involved in local politics. Community organizations worked with city councils, mayors, and county governments to secure local support for Holodomor Remembrance Days. These actions were particularly visible in Chicago, Cleveland, Philadelphia, and other cities in the northeastern states, where Ukrainian American populations are concentrated. By connecting remembrance events with municipal politics, the diaspora gained recognition as a socially active and reliable civic community.

Through community events, the Ukrainian Americans began engaging directly with their congressional districts, identifying sympathetic representatives and encouraging voter participation. Community leaders built relationships with candidates, hosted town halls, and supplied background information on Ukraine-related issues. These district-level connections were later decisive when legislators introduced or co-sponsored Holodomor recognition resolutions in Congress.

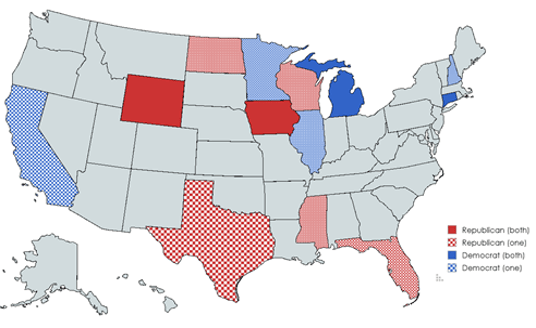

Perhaps the most important forces that pushed the United States to recognize Holodomor as genocide were the state assemblies and senates. Ukrainian diaspora organizations lobbied state lawmakers, many of whom represented constituencies with significant Ukrainian populations. Between 2016 and 2019, over a dozen states, including California, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Michigan, and New Jersey, adopted Holodomor genocide resolutions or gubernatorial proclamations. These achievements demonstrated the diaspora’s political capacity and helped to influence future national policymakers. Especially significant is that before the national recognition in March 2018, seven states and Washington, D.C. had already recognized Holodomor as genocide, mostly doing so in 2017.

At the federal level, the Ukrainian diaspora leveraged decades of advocacy to institutionalize its influence. Organizations such as the Ukrainian Congress Committee of America (UCCA) and Ukrainian National Women’s League of America (UNWLA) worked closely with members of the Congressional Ukrainian Caucus and Senate Ukraine Caucus. This collaboration led to bipartisan resolutions, such as the 2005 House resolution, the 2006 Holodomor Memorial Act, and most importantly, the Ukrainian Caucus-sponsored2018 Senate Resolution, recognizing the famine as genocide. After 84 years, the resolution that didn’t pass in 1934 was finally adopted due to increased influence and organization at all levels of the Ukrainian diaspora.

Coalition Building

Inter-Diaspora Coalitions

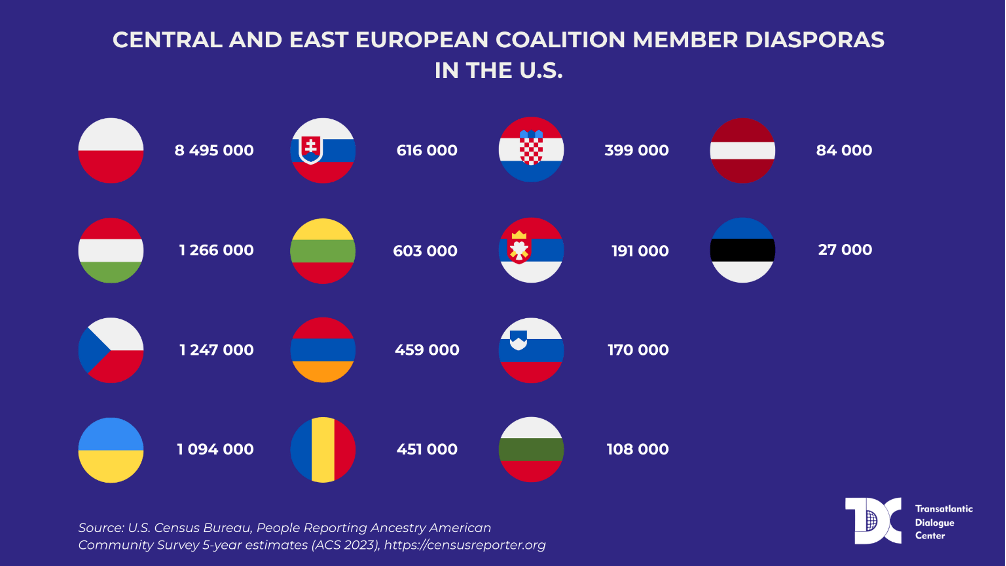

Russian aggression is the most pressing issue not only for Ukraine and its diaspora but also affects many countries in Eastern and Central Europe. As such, the Ukrainian diaspora has found many allies in other diasporas. Many of those states have cooperated with the Ukrainian diaspora since the Cold War. Those connections have been revitalized with the current situation and possess an important possibility to enhance the Ukrainian diaspora’s voice in American politics. The Central and Eastern European Coalition, which was established in 1994, contains 18 main national organizations of Eastern and Central European diasporas. This organization has focused heavily on supporting Ukraine, and considering that those diasporas make up a significant portion of the United States population, the significance of this should not be underestimated. Particularly, the votes of the Polish diaspora have at different times in its history changed the outcomes of American elections.1 This fact was not lost on the American politicians; for example, the Harris campaign in 2024 ran ads targeting the Polish, Ukrainian, and Lithuanian diasporas in the state of Pennsylvania.

It has been the Baltic diasporas that have proven to be the most supportive of Ukraine. Both the Joint Baltic American National Committee y the Baltic American Freedom League have already spent considerable time and money lobbying for pro-Ukrainian legislation in Congress. This cooperation has its roots in the Cold War, when diaspora groups of the Baltic states and Ukraine were each other’s main advocacy partners.

Domestic Political Co-operation

For the American Ukrainian cause to receive support beyond the diaspora, it is absolutely vital for advocacy to include organizations beyond the narrow Ukrainian focus. The Ukrainian diaspora has, since the Cold War, and especially since 2014, established connections with think tanks, advocacy groups, and other institutions that focus on democracy promotion, human rights, and international security. Many prominent NGOs have been supporting the Ukrainian diaspora, such as the Atlantic Council, the National Democratic Institute (NDI), the International Republican Institute (IRI), and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). These have been continuously publishing materials about Ukraine and the war, influencing the decision-makers in Washington. In 2014, the U.S.-Ukraine Foundation (USUF) established the Friends of Ukraine Network (FOUN) concentrating former leading officials and experts in task forces helping Ukraine.

International Networks of Ukrainians

The American Ukrainian diaspora has long been one of the leading Ukrainian diasporas in the world. It was in New York in 1967 that the Ukrainian World Congress (UWC) was established. The American Ukrainian community was one of the most active members of UWC during the Cold War, and while its headquarters are in Toronto, Canada, the UWC Mission to the United Nations is based in New York. Ukrainian diasporas have coordinated worldwide events such as the Stand with Ukraine demonstrations and Holodomor remembrance events held worldwide each year. Historically, the American Ukrainian diaspora has had strong ties with the Canadian Ukrainian diaspora. Canada has the second-largest Ukrainian diaspora after Russia, with around 1.25 million Canadians, or 3.4% of Canada’s population, reporting Ukrainian ancestry. Both diasporas share history and identity, and due to that, have always cooperated.

Diaspora Contribution to Independent Ukraine

Support for Independence

The gradual disintegration of the Soviet Union in the 1980s and 1990s led to a fundamental change in Ukrainian society, culminating in Ukraine declaring independence on August 24, 1991. As Ukraine established itself as a free nation, it faced a difficult challenge of defining its politics outside of the soviet legacy; a significant challenge compared to the Baltic states, which had been independent for decades before the Soviet occupation. This allowed the diaspora community to participate in the domestic politics of Ukraine for the first time.

In the lead-up to the referendum on 1st of December 1991, the North American diaspora played a key role in funding the Rukh movement. For example, the Toronto branch collected 200,000 dollars (around 250,000 euros today) to promote independence. This was mostly the extent of the political power of the diaspora in Ukraine, as even though diaspora members did fund some smaller parties in Ukraine, the impact of such movements was almost negligible.

Many diaspora members travelled to Ukraine after independence, and some stayed to work there, mostly as young professionals and governmental advisors. It should also be noted that many American-born Ukrainians went on to become important politicians in Ukraine post-independence, such as former Minister of Healthcare Ulana Nadia Suprun, former Minister of Finance Natalie Ann Jaresko, and former First Lady of Ukraine Kateryna Yushchenko.

Diaspora’s interest in Ukrainian politics was revitalized during the Orange Revolution and Revolution of Dignity. During the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election, the UCCA observer testified to voter intimidation. The UCCA was very active during the Orange Revolution, organizing the largest election observation mission in Ukraine’s history with over 2500 observers. In fact, the Ukrainian American community and its activists, such as Adrian Karatnycky, were so important to guaranteeing fair elections that it led some to believe the Orange Revolution was steered by the CIA. During the Euromaidan protests, the diaspora community organized protests all over the U.S. in support. As the protest evolved, the diaspora provided increasingly more monetary and humanitarian aid.

Aid and remittances

Following independence in the 1990s, Ukraine faced serious economic troubles, life expectancy declined, and crime rose to unprecedented levels. Besides lobbying the U.S. government to relax the immigration requirements and helping those who arrived in the country, the Ukrainian Americans, both older waves as well as the people who arrived post-independence, became an important source of aid and remittances for Ukraine.

First aid campaigns by the American Ukrainian community started even before the Ukrainian independence, as the United States chapter of the “Children of Chernobyl” organization sent over 40 million dollars in humanitarian aid to Ukraine. After independence, the flow of both official and unofficial aid increased significantly. Hundreds of diaspora organizations provided humanitarian aid to Ukraine, and many diaspora members supported their family members. However, by the mid-1990s, both the NGOs and the diaspora members had become more skeptical about providing help due to multiple high-profile cases of corruption in Ukraine. By the 2000s, the main source of money sent from the U.S. to Ukraine was the remittances sent home by Ukrainians who came to work in the U.S. after independence.

After the start of the Russo-Ukrainian war in 2014 and the full-scale invasion of 2022, remittances fell, most likely due to either Ukrainian men working abroad going back to Ukraine or due to their families leaving the country. During the first years of war, the number of organizations providing both military and humanitarian aid increased significantly, but the coordination remained mostly decentralized and community-based. It was not until 2022 that more significant aid networks emerged in the diaspora, and the focus shifted from informational campaigns to direct monetary aid.

Diaspora’s advocacy (the REPO Act)

Diaspora advocacy has proved to be the main driving force for a lot of legislation aimed at supporting Ukraine in the war. One example of the efforts of the American Ukrainian diaspora is the push for the passage of the Rebuilding Economic Prosperity and Opportunity for Ukrainians Act, a.k.a. the REPO Act. This act provided the backing for the confiscation and disposition of Russian sovereign assets and was backed by an organized effort of the diaspora community.

The idea of confiscating Russian assets in the United States gained its supporters in Washington after the 2022 invasion, even though some in the diaspora had been advocating for that since the start of the war. Following Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukrainian American communities, NGOs, and advocacy networks began campaigns calling for Russia to pay for reconstruction through seized assets. The debate over the legality of such seizures continued for most of 2022. In October of 2022, senators Jim Risch and Sheldon Whitehouse proposed the first version of the Russian Elites, Proxies, and Oligarchs Act (REPO Act), but they failed to gather sufficient support for it.

In the second half of 2023, the campaign for the renewed REPO Act heated up once again. In June 2023, the members of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, mainly from the Ukrainian Caucus, reintroduced the REPO Act in the House, and on the same day, it was also reintroduced in the Senate. As the bills made their way through various committees, the American Ukrainian diaspora became active to support them. In the center of those efforts was the Ukraine Action Summit in October of 2023. During the summit, the REPO Act was one of the main discussion topics, and meetings with lawmakers managed to secure an additional 23 cosponsors from the House and 2 from the Senate. At the same time, there were multiple actors spending money lobbying as well, for example, Razom Inc., Joint Baltic American National Committee, Baltic American Freedom League, and Foundation for Defense of Democracies all hired lobbyists to gain support for the bill. The REPO Act was passed and signed into law in April of 2024. In October of 2024, the United States used the REPO Act to cover 20 billion dollars’ worth of loans to Ukraine, and in September of 2025, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee proposed the REPO Implementation Act of 2025 to enhance the bill further.

Internal Challenges

Generational divides

The Ukrainians have arrived in the United States in multiple distinct waves. Diverging in their priorities and identity, these waves have often clashed and contradicted each other politically. American political polarization and the Russo-Ukrainian war have, in many ways, supercharged these divisions, even as supporting Ukraine has revitalized the Ukrainian identity. The conflicts between the second and the third wave immigrants, as well as between the third wave and the fourth wave immigrants, were more prominent during the Cold War, but their impact is still prominent in communities. The refugees that have arrived since the start of the war in 2014 relate more to the third wave political emigrants than to the fourth wave economic emigrants.

Diverse priorities

Compared to the Ukrainian diaspora in Canada, political mobilization has always been less central for the diaspora in the U.S. During the Cold War, the Ukrainian diaspora, alongside other Eastern European diasporas, leaned Republican due to the Republican Party’s anti-communist stance. This is still true today, even as many Ukrainians are divided by the Republican Party’s shaky stance on the Ukrainian issue. This can be attributed to the fact that the diaspora, being more religious and socially conservative than the average, tends to focus primarily on American internal politics. This is especially true for the evangelical Ukrainians from the fourth wave of migration.

Organizational competition and decentralization

Throughout the history of the American Ukrainian diaspora, it was plagued by infighting between different diaspora organizations carrying contradicting political ideas. This limited the cooperation between them for the entire Cold War. The most significant was during the Thirteenth Congress of UCCA, held in 1980, where the Ukrainian Liberation Front tried to take control over the UCCA, leading to the organization breaking in two. In the face of the Russo-Ukrainian war, the Ukrainian diaspora has been able to present a mostly united front, but once the conflict changes, the differences in aims will strain the ties between different organizations and their members.

Moreover, despite the consolidation of community organizations on the national level, the main community force still lies in the local diaspora groups. These groups have a significant everyday cultural impact on American Ukrainians, and they have been vital in organizing grassroots support for Ukraine. However, their impact on national politics is limited, and they lack the ability to coordinate with each other.

Sustainability of activism

the war continues, it is increasingly difficult to sustain the support of the American people and the activity of Ukrainian activists. Organizations across the globe have seen a decrease in donations and volunteers as the coverage of the war decreases. This will make it increasingly hard for the diaspora organizations to provide the support that Ukraine is expecting from them and to maintain the political power they have cultivated in Washington since 2022. If the war ends, the need for supporting Ukraine does not stop, but the extent to which the American Ukrainian community can support the rebuilding might be seriously limited by the lack of volunteers and funds.

Perils of partisanship

Over the past years, the political divide in the United States has deepened, and the Ukrainian diaspora has been deeply affected. Firstly, the diaspora itself is divided on political issues within the U.S., as a big part of the Ukrainian diaspora identifies more with conservative views, which do not align with the newer wave of younger emigrants. Secondly, supporting Ukraine has increasingly become a partisan issue both with the voters and within the Government. Polls show that support for Ukraine has drastically fallen amongst the republican voters, leading to the politicization of the topic. The changing views on Ukraine by the current administration have undermined the support in the House and Senate, which has historically been bipartisan. This presents the diaspora with a complicated task of increasing support for Ukraine while trying not to take sides in the boiling climate of U.S. internal politics.

Identity politics

The Ukrainian diaspora in the U.S. has historically been driven by strong identity and community ties. The ethnicity, language, and religion were the borders that divided communities and diaspora organizations; many groups were discounted as diaspora members due to perceived “lack of Ukrainianness”. Since the end of the Cold War, Ukraine, as an independent country, has made it easier for different ethnic groups from Ukraine to identify with the diaspora. Still, until the Maidan Revolution and the start of the war, this process was very slow, and to this day, the organizational divides persist. For those Americans whose parents or grandparents were excluded from diaspora, the road to connect themselves to Ukrainian American identity will be long and something that only steadfast work from the Ukrainian government and diaspora organizations can accomplish.

Future Outlook

Elections of 2026

Following the 2024 presidential elections, the U.S. is preparing for the next electoral cycle, with less than a year remaining until the 2026 midterms. It is predicted to be extremely heated as all 435 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives and 35 of the 100 seats in the U.S. Senate will be contested, and Ukraine will certainly be one of the main topics. It is likely that the main effort of the current administration in the lead-up to the election will go towards securing a peace treaty in Ukraine. Lately, the number of Republican voters supporting Ukraine has begun to rise again, showing that the impact of the “Ukrainian issue” may be a more significant determinant in the elections than previously thought.

For the Ukrainian diaspora to have a real influence in this election, local communities must take charge and organize in a way that is visible to House and Senate candidates, gathering votes not only from the Ukrainian diaspora but perhaps even more so from the other Eastern European diasporas. The Center for Demographic and Socioeconomic Research of Ukrainians in the United States has estimated that Ukrainian and Polish diasporas together make up over 5% of voters in eight states, meaning that, at least theoretically, they have the power to significantly influence the elections. All of this, if used correctly, will give the Ukrainian diaspora significant leverage in the 2026 elections.

Conclusion

Summary

The Ukrainian American diaspora has evolved from an ethnic community focused on cultural preservation into an important political actor with measurable influence in both Ukraine and the United States. Its success shows the importance of national diasporas as a foreign policy tool, from grassroots activism and cultural diplomacy to institutional lobbying and communication in Washington.

The Ukrainian American diaspora has long fought for the recognition of Ukraine in the United States. During the Cold War, they positioned themselves as advocates for human rights and freedom for “captive nations,” shaping American perceptions of Soviet oppression and introducing the idea of Ukraine as a distinct nation. After 1991, this focus shifted toward securing recognition of Ukraine’s independence and gaining support for the nation. Since 2014, and especially after the full-scale Russian invasion in 2022, the diaspora’s role has expanded dramatically, becoming a vital conduit of humanitarian aid, strategic communication, and political influence.

In American internal politics, Ukraine has moved from the margins of foreign policy to the center of partisan debate. While the “Ukrainian question” has at times been entangled in conspiracy theories and partisan polarization, Ukrainian American organizations have generally maintained bipartisan credibility, emphasizing democracy, freedom, and resistance to aggression.

The strength of the Ukrainian American diaspora lies in its ability to participate in politics at both the local and national levels. From local parishes and state assemblies to Congress, Ukrainian Americans have successfully built influence “up the ladder,” demonstrating that consistent civic participation and pressure can produce tangible political outcomes.

Yet challenges persist. Generational divides, limited issue-based voting, and competition among organizations have sometimes hindered the cohesion of the diaspora. To remain effective, Ukrainian American advocacy must continue evolving, expanding its political action tools, coordinating across organizations, and working closely with allied diasporas, such as those of Poland and the Baltic states. Sustaining bipartisan support will also require balancing moral appeals with pragmatic policy arguments that align Ukraine’s security with U.S. national interests.

Ultimately, the Ukrainian American diaspora’s greatest strength lies in its ability to bridge communities, nations, and narratives. As both a moral voice and a policy actor, it stands at the intersection of civic activism and statecraft, serving not only as a representative of Ukraine’s struggle for freedom but also as a contributor to the ongoing definition of America’s role in international politics.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations with which the authors may be associated.

This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. It’s content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.