2 MB

Key takeaways

- A growing number of Eastern European countries are withdrawing from the Ottawa Convention, arguing that current security realities demand rearming with anti-personnel mines.

- Originally signed in a period of post-Cold War optimism, the Convention reflected a shift toward human security and was seen by many Central and Eastern European states as a gateway to NATO and EU integration.

- That foundational logic is now being challenged by a new strategic environment, where Russia’s refusal to join the treaty—and its widespread mine use in Ukraine—creates a dangerous asymmetry for neighboring countries.

- These states frame their withdrawal not as an abandonment of humanitarian norms, but as a necessary adaptation to defend territorial sovereignty against a militarily unconstrained adversary.

- While NATO countries remain committed to broader arms control regimes, the precedent of treaty withdrawal under national security pretexts could spread to other agreements governing cluster munitions or conventional weapons.

- The erosion of even selective disarmament norms risks undermining the legitimacy of the global arms control system—particularly if more states begin to prioritize strategic deterrence over humanitarian commitments.

Why Are Countries Withdrawing from the Ottawa Treaty?

In recent months, several countries bordering Russia—including Ukraine, Poland, and the Baltic states—have announced their intent to withdraw from the Ottawa Convention banning anti-personnel mines. This rare move challenges long-standing humanitarian norms and raises a legitimate question: Do such decisions reflect isolated wartime exceptions or a broader shift in international arms control regimes?

The Origins of the Ottawa Convention

It is useful to look at the historical background to understand the context in which the Ottawa Convention and similar international agreements were created and adopted. The 1990s, the period of the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War, was a key period that marked the beginning of active discussions on the prohibition of anti-personnel mines. During this period, the international arena saw a transition from ideological confrontation between the two blocs to attempts to develop universal humanitarian norms aimed at reducing the consequences of armed conflicts.

One of the most pressing problems at that time was the widespread use of anti-personnel mines, tens of millions of which remained in conflict zones, especially in Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Balkans. The consequences of their use were long-term and far-reaching, creating humanitarian disasters and threatening the safety of civilians. This led to a shift from state-centric approaches to security to the concept of human security, which became part of the new humanitarian agenda.

However, the convention was not adopted solely on humanitarian grounds. The widespread use of anti-personnel mines caused significant damage to agricultural development, hampered infrastructure reconstruction, and impeded the economic rehabilitation of post-conflict regions. In addition, for a number of states, especially in Central and Eastern Europe (Poland, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia, and others), accession to the Ottawa Convention was seen as a demonstration of commitment to democratic and humanitarian values, which was considered one of the political and reputational conditions for integration into the structures of the European Union and NATO.

There were also technical considerations. Some states, including Germany, Canada, Sweden, and Norway, concluded that anti-personnel mines were an obsolete type of weapon and could be replaced by modern technologies, including sensors, unmanned systems, reconnaissance, and early warning systems.

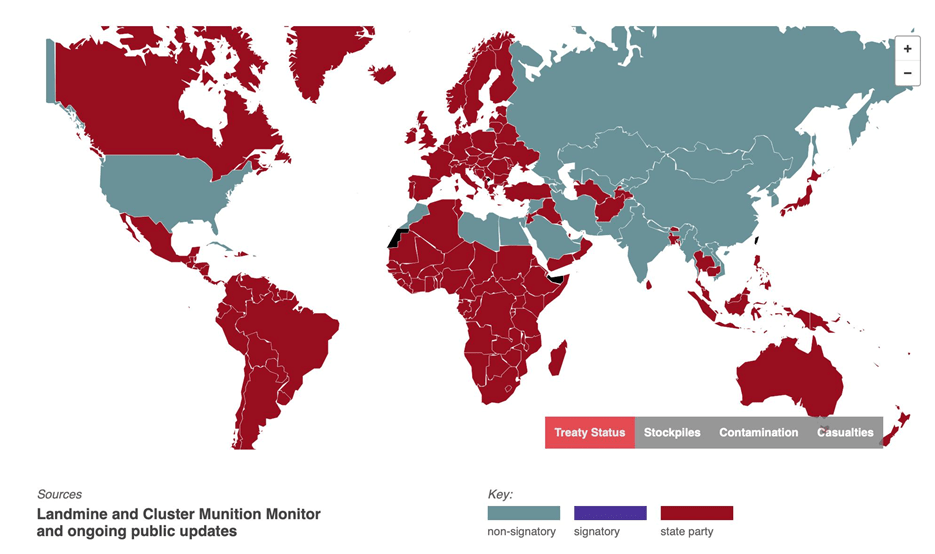

However, not all countries considered it possible to renounce the use of mines. Among the states that refused to accede to the Ottawa Convention are, in particular, the United States, the Russian Federation, China, India, and Pakistan. In their view, anti-personnel mines remain an important element of defense strategy, particularly in the context of border security or conflict in disputed territories (such as the situation between India and Pakistan in the Kashmir region). In addition, these countries pointed to an emerging imbalance: the renunciation of mines creates a military-strategic asymmetry, giving an advantage to potential adversaries who are not bound by similar commitments. This explains their refusal to participate in multilateral agreements restricting specific types of weapons.

The Russian Threat and the Return of Mines as a Strategic Tool

Having considered the historical context, it is worth asking what the arguments are of the states that have announced their withdrawal from the Ottawa Convention. The rhetoric and motives of these countries shape a single narrative. The main argument is as follows: when the convention was signed and ratified, the possibility of armed aggression by the Russian Federation against European states, let alone scenarios of annexation of territories, was not taken into account.

Since Russia is not a party to the Ottawa Convention and systematically uses anti-personnel mines during its invasion of Ukraine, a number of countries directly bordering Russia have no guarantees that such weapons will not be used against them. This creates an asymmetrical situation in which one side has a potential tactical advantage due to means that are prohibited for other parties to the agreement. In this context, these states view withdrawal from the Ottawa Convention not as a renunciation of their international humanitarian obligations, but as a necessary measure to ensure national security and protect their territorial integrity and sovereignty.

The withdrawal from the Ottawa Convention by countries on NATO’s eastern flank is not merely a tactical adjustment. It signals a growing view that existing arms control regimes are no longer adequate to protect national security in a high-threat environment. These moves reflect a shift in thinking: that humanitarian norms, while ideal, may be overridden when adversaries operate outside the same legal boundaries.

Are Other Treaties at Risk?

A sudden change in rhetoric raises a logical question: could this trend spread to other international arms control agreements? It seems possible, but with an important condition. NATO member states are not likely to take steps that could lead to an escalation of the conflict. All international legal obligations that these countries are renouncing are interpreted by them exclusively in the context of defending their own territory and reducing the risk of direct military confrontation with the Russian Federation.

It should be emphasized that any agreements involving not only restraint but also elements of offensive action or potential retaliation, such as:

- The Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR, 1987),

- The Hague Code of Conduct on Ballistic Missiles (HCoC, 2002),

- Strategic Arms Reduction Treaties (START I, II, New START)

are unlikely to be adopted. The strategic line of states directly bordering Russia is to minimize the likelihood of armed conflict or, at least, to reduce its scale and consequences. Rejecting these conventions would do the exact opposite.

However, there are international agreements from which nations could theoretically withdraw under the pretext of self-defense, such as:

- The Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM, 2008);

- United Nations Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW, 1980), in particular Protocol II on mines, booby traps and other devices;

Each of these agreements restricts the use of certain categories of weapons which, in the scenario of a change in the geopolitical situation or an increase in threats, may be considered by states as instruments of defensive deterrence. Consequently, in view of the deteriorating security situation on Europe’s eastern flank, it cannot be ruled out that the issue of revising commitments under these documents may be put on the agenda.

Could This Be the Start of a Global Arms Control Backslide?

While recent withdrawals from the Ottawa Convention may appear isolated, they raise broader concerns about the resilience of international arms control regimes in an increasingly insecure world. NATO countries are unlikely to abandon core disarmament agreements without the outbreak of a major direct conflict with Russia. However, the precedent set by Eastern European states, prioritizing national defense over humanitarian norms, could prompt similar decisions elsewhere if the global security climate continues to deteriorate.

A global domino effect remains unlikely in the short term, especially among states not engaged in active conflicts. Yet in regions facing heightened military threats or asymmetric warfare, countries may begin to view certain treaties, particularly those limiting defensive capabilities, as constraints rather than safeguards. In such cases, governments could reassess or withdraw from agreements like the Convention on Cluster Munitions or the CCW protocols, framing their actions as necessary adaptations to new threat environments.

Ultimately, the erosion of even a few disarmament norms could weaken the entire architecture of international humanitarian law. As more states weigh the strategic costs of legal restrictions, the legitimacy and enforceability of global arms control standards may be gradually undermined.

Conclusion: A Cautionary Shift, Not a Trend—Yet

The recent withdrawals from the Ottawa Convention do not yet amount to a systemic unraveling of arms control norms, but they send a strong signal. In a deteriorating security environment, humanitarian principles may be increasingly subordinated to strategic imperatives. The precedent these countries are setting could open the door for a broader reevaluation of other treaties should geopolitical tensions intensify. As history shows, arms control regimes are only as strong as the strategic stability that underpins them.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations with which the authors may be associated.