2 MB

Key Takeaways

- Hungary’s Divergence from EU Policies: Since the early 2010s, Hungary has diverged from key EU principles, particularly regarding migration policies, misuse of EU funds, and violations of democratic rights, creating tension with Brussels.

- Rule of Law Crisis: Hungary’s democratic institutions, including judicial independence and media freedom, have weakened under Viktor Orbán’s government, leading to criticism from EU institutions over rule-of-law violations.

- Blocking Financial Aid to Ukraine: Hungary has blocked over €9 billion in EU financial aid intended for Ukraine under the European Peace Facility (EPF). This includes blocking partial reimbursements for arms and other critical assistance. Hungary has also opposed 41% of EU resolutions supporting Kyiv, disrupting EU unity and decision-making.

- EU Financial Penalties: The EU has frozen up to €30 billion in funds earmarked for Hungary, including allocations for recovery, cohesion, and home affairs, as a result of rule-of-law violations. Financial sanctions have proven to be the EU’s most effective tool in pressuring Hungary.

- Hungary’s Leverage through Veto Power: Hungary has used its veto power to block important EU decisions, especially those related to sanctions against Russia and financial aid to Ukraine, leveraging this position to negotiate the release of frozen EU funds.

- Dependency on EU Funds: Despite its disputes with the EU, Hungary remains heavily reliant on EU funding, which plays a critical role in sustaining its economy. This dependency is a major reason why Hungary is unlikely to consider leaving the EU.

Hungarian policy has been at odds with the European Union since the early 2010s. Migration policies condemned by the European Court of Human Rights, alleged misuse of the EU funds, and consistent violations of the rights and freedoms of Hungarian citizens cause exasperation of many Brussels politicians. The divergence in values became even more evident in February 2022, when the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine started. As of May 2024, Hungary has blocked a total of €9 billion in financial aid to Kyiv that the EU attempted to pass, as well as 41% of the EU’s proposed resolutions on Kyiv.

Budapest’s controversial actions have disrupted EU unity, leading member states to seek ways to resist Orbán. As a result, the EU has initiated multiple legal proceedings against Hungary. This research aims to examine the instruments the European Union employs in that regard, analyze their efficiency, and evaluate Budapest’s prospects for its future in the EU.

Hungary’s Non-Compliance with EU Policies

First, we will look into how exactly Hungary’s policies have been deviating from EU legislation.

The Rule of Law Crisis

Democracy in Hungary has been weakening since Viktor Orbán became Prime Minister in 2010. In 2012, the government reformed the electoral system to benefit the ruling Fidesz party. The judiciary also became less effective, with the new Supreme Court administration system allowing the selection of a court leader loyal to the government.

Finally, the Fidesz government also extended its political power to public space, imposing control mechanisms in the media, academia, and civil society at large. As for the media, every third journalist admitted to having withheld or distorted information in order to avoid negative consequences. The academic freedom, in its turn, was reportedly violated in 2018, when a pro-government Hungarian magazine published a list of more than 200 people labeled as ‘mercenaries’ and allegedly funded by George Soros to overthrow the government.

Unlawful Migration Policies

In 2015, the movement of migrants into the EU increased significantly. Hungary’s borders were crossed by 411,515 irregular migrants. Trying to avoid dealing with them, Hungary constructed fences at the Southern borders with Serbia and Croatia and reduced legal protection offered to the refugees. Climbing through or damaging a fence was criminalized. In 2016, the police got a permit to push migrants to the other side of the fence. Further amendments significantly reduced support mechanisms provided for asylum seekers. Refugees who applied for asylum could only do so in the so-called transit zone and were detained throughout the time of the procedure.

Photo: Dániel Németh. Source: BalkanInsight

These policies were highly criticized on the basis of international and EU law. Because of reception conditions in Budapest, several EU member states halted transfers to Hungary under the Dublin III mechanism. The European Court of Human Rights also condemned the above measures in the Ilias and Ahmed v. Hungary case in March 2017 and then repeatedly in November 2019.

Ukraine Financial Aid Blockages

In February 2022, Russia started a full-scale invasion against Ukraine. The European Union showed solidarity with Kyiv and adopted a few packages of sanctions and other restrictive measures against Moscow. Shortly after, the European Commission proposed financial support measures for Ukraine. Since then, a great deal of financial aid packages have passed, which have been extremely important in funding the fight against Russian forces and supporting the economic and humanitarian resilience of Ukraine.

Under the Common Foreign and Security Policy framework, this decision-making process and renewal of certain measures require unanimity among the Member States. However, Hungary has been reluctant to extend its agreement over adopting sanctions and aid packages. In December 2022, Budapest refused to approve a loan of €18 billion to Kyiv to support various needs, including the operation of hospitals, emergency shelters, and the electricity supply. Some recent instances include blocking a €50 billion aid in December 2023 and a €6.6 billion package in May 2024.

Circumventing Russian Oil Sanctions

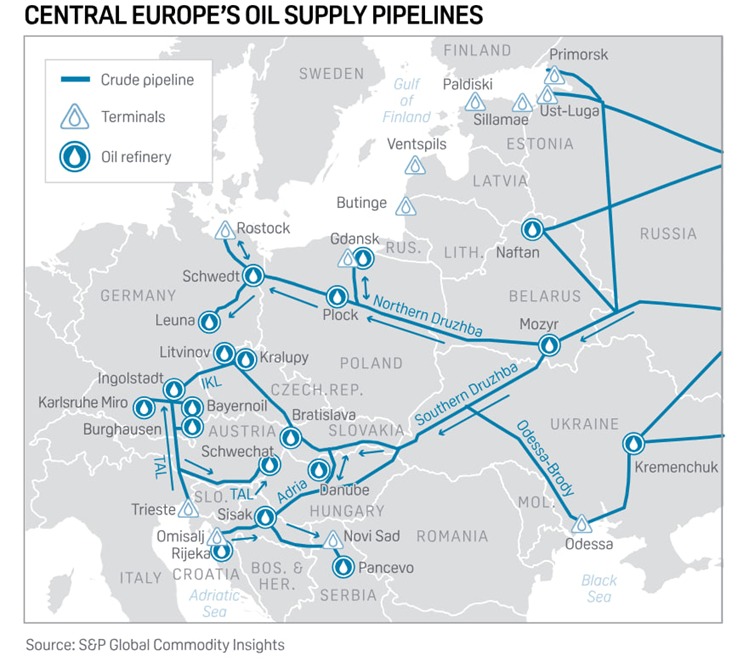

In June 2022, the Council of the EU adopted a sixth package of sanctions, which included prohibition of the purchase, import, and transfer of sea-shipped crude oil and specific petroleum products from Russia to the EU. There was, however, an exception for those EU member states that are dependent on Russian crude oil due to geographical position, including Hungary and Slovakia. Hungary, as well as some other Central European countries, have so far been successful in avoiding the bans through exemption by importing Russian oil through the pipeline system Druzhba.

Considering Hungary’s reliance on the Russian energy supply, it is no surprise that Budapest expressed frustration after Ukraine imposed an embargo on the Russian oil company Lukoil. In response, they started importing oil from another Russian supplier, Tatneft. EU member states showed dissatisfaction that Budapest continued purchasing Russian energy while they had to refrain. However, Brussels officially refused to intervene.

EU’s Legal Framework for Penalizing Hungary

In response to many of the above-mentioned violations, the EU has used legal measures against Budapest. In this section, we will analyze these instruments and estimate their effectiveness.

Article 7

Article 7 of the Treaty on the European Union (TEU) aims to ensure that all Member States respect the common values of the EU, including the rule of law. In case there is a Member State that violates one of the values, two procedures can be applied, namely, the preventive mechanism and the sanctioning mechanism. The former allows the EU to give a warning to the Member State that risks making a serious breach, while the latter confirms the breach was made and enables the Council to suspend certain rights of the Member State, including its voting rights in the Council.

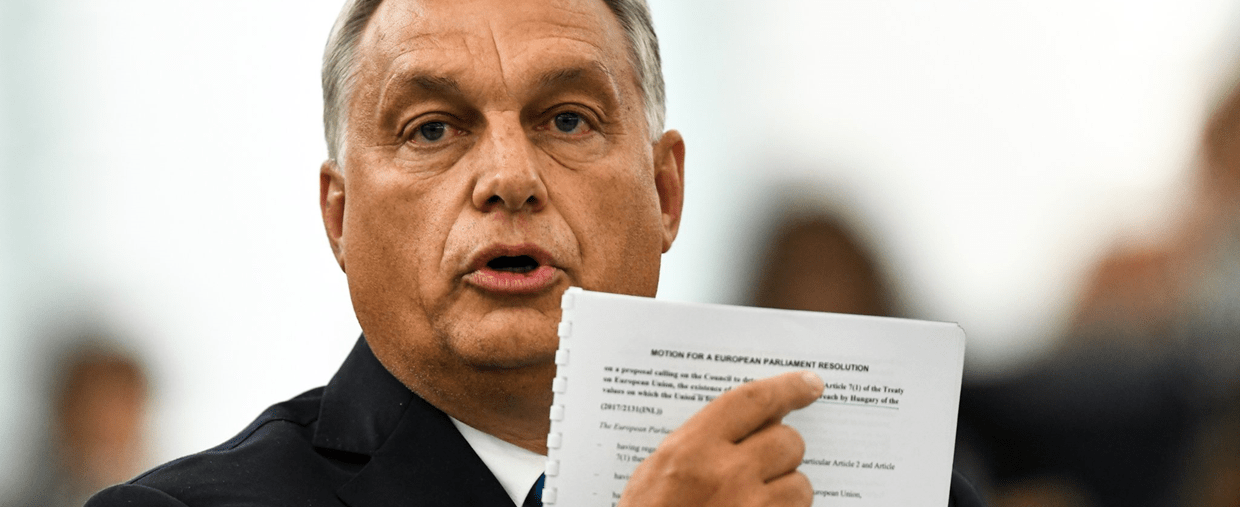

The Article 7 procedure was triggered against Budapest in September 2018, when the European Parliament concluded that there was a ‘clear risk of a serious breach of the EU founding values in Hungary.’ In particular, Orbán’s government was accused of weakening judicial independence, perpetuating cronyism, diluting media pluralism, abusing emergency powers, passing anti-LGBT legislation, and hindering asylum rights.

However, the procedure has not progressed since then. Hungary has been under the first chapter of Article 7 for six years. In May 2022, the European Parliament (EP) adopted a resolution calling on incoming presidencies to organize hearings under Article 7 ‘regularly and at least once per Presidency.’ The seventh and last such hearing occurred under the Belgian Presidency on 25 June 2024.

In September 2022, the European Parliament passed a resolution calling for action regarding Article 7 procedure. MEPs stated they were worried ‘about several political areas concerning democracy and fundamental rights in Hungary.’ They also noted the ‘inability of the Council to make meaningful progress in countering democratic backsliding’ and warned that ‘any further delay in acting under Article 7 rules to protect EU values in Hungary would amount to a breach of the principle of the rule of law by the Council itself’.

With these considerations in mind, lawmakers have called for the EU to impose the second step. It would shift the procedure from indicating a ‘risk of a serious breach’ to stating that the breach has already happened, i.e., determining the ‘existence of a serious and persistent’ violation. However, this phase can only be initiated after one-third of member states or the Commission submit a proposal. So far, none of them has expressed their intention to do so.

Article 7 procedure was also invoked against Poland in 2017 after the then-governing Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, PiS) took political control over the judiciary and challenged the primacy of EU over national law. In May 2024, the procedure was officially closed with the explanation that Poland had launched a series of legislative and non-legislative measures to address these concerns. Even so, some claim that the wrap-up, based on ‘commitments’ by Poland’s new coalition government under Donald Tusk, was rushed, and it wasn’t taken into account that few concrete measures were actually implemented.

Overall, the Article 7 procedure appears to be too bureaucratic and slow to be successful. Not only do decisions take years to be formed and made, but the accused state might not even appear to be concerned by them. At the same time, one should not completely write off the potential of Article 7. In case the Council was to activate the next step, a withdrawal of voting rights from Hungary would be just one vote away. This would strip Budapest of important leverage and clear the way for adopting decisions without the need to negotiate for veto withdrawal.

Financial instruments

EU legislation offers multiple punitive mechanisms that can lead to financial sanctions. To name a few, these include budget conditionality mechanisms and infringement procedures.

Budget conditionality mechanism, a new regime of conditionality protection, came into force in 2021. It allows the EU to suspend certain payments or make financial corrections regarding the Member State, in case it violated any principles of EU law. It’s worth noting that this mechanism is different and independent from the Article 7 procedure, and focuses on finance and economic measures rather than values.

On 27 April 2022, the European Commission officially triggered the conditionality mechanism against Hungary. This meant the beginning of a process of assessment and information exchange with Budapest, which lasted until mid-September. On 18 September 2022, the Commission concluded that systemic breaches of the principles of the rule of law still persisted in Hungary, and therefore, the Council of the EU should implement measures to protect the Union budget.

In December 2022, the Committee of Permanent Representatives in the EU found the required majority to impose measures for the protection of the Union budget against the consequences of breaches of the rule of law in Hungary. As per the decision, around €6.3 billion in budgetary commitments were to be suspended. Even though Orbán’s government had adopted a range of remedial measures before, the European Commission concluded that those were not effective, and funds would be frozen regardless.

On the other hand, the so-called infringement procedure stems from the EU treaties and may be applied against the Member State in case it fails to implement EU law or newly adopted national legislation violates EU law. The process is triggered by the Commission. It can then pass the case to the Court of Justice, which might impose financial sanctions.

Since 2017, the EU has been opening from 22 to 32 infringement cases against Hungary per year. However, bringing the infringement procedure to the court is a path filled with obstacles. It can take up to one year for the Commission to refer the case to the Court of Justice, followed by another year or two for the hearings to take place. Even if the risk of violation is stated at the beginning, it can easily be dismissed because the consequences of the breach go beyond EU competencies. Moreover, even if the court confirms the violation and imposes measures, actually implementing them can take another several years.

One of the infringement cases dates back to 2021 when Budapest adopted the law commonly referred to as anti-LGBTQ+ law. It prohibited or limited access to content that portrayed the so-called ‘divergence from self-identity corresponding to sex at birth, sex change or homosexuality’ for individuals under 18. The Commission began infringement proceedings in July 2021, stating a potential breach of EU legislation. After five months, it was concluded that Hungary had failed to fulfill its obligations. In 2022, when there was no satisfactory response, the Commission referred the case to the Court of Justice of the EU.

In February 2023, the case was published in the official journal of the EU. At this point, it was important to secure support from the Member States. Human rights NGOs worked hard to do so and succeeded in gathering support from largest-ever number of intervening states. The hearing was supposed to take place in summer 2024, but as of now, there has been no updates on this issue.

at Hungary’s parliament in protest against anti-LGBT law in Budapest, Hungary, July 8, 2021. Source: Reuters

Another infringement case worth mentioning was initiated against Budapest two years ago and renewed this summer. Specifically, it dealt with the migration policies mentioned above. In December 2020, the Court of Justice ruled that Hungary had limited access to asylum procedures for those seeking international protection. In particular, it was unlawfully keeping asylum seekers in so-called “transit zones” under detention-like conditions and violating their right to appeal. However, the Hungarian government protested against these accusations and largely ignored the verdict. Only “transit zones” have been closed since then.

Because of inaction, the European Commission filed a legal action once again. As a result, in June 2024, the Court reiterated that Hungary was “disregarding the principle of sincere cooperation” and “deliberately evading” the implementation of the EU’s asylum laws, causing significant impacts on neighboring member states. This time, a €200 million fine was also imposed as a lump sum, plus a €1 million fine for each day the wrongdoing persists. Orbán expressed frustration over such a decision, refusing to pay anything. In August 2024, he even offered to send migrants to Brussels by bus. ‘If Brussels wants illegal migrants, Brussels can have them,’ State Secretary said.

Nevertheless, thanks to the existence of numerous procedures, various financial sanctions have been successfully implemented. In total, the number of frozen EU funds for Hungary amounted to 28.6 billion euros in December 2023. These funds can be divided into three macro-areas, which proceed in parallel:

- National Recovery and Resilience Plan (5.8 billion), blocked due to violations of the rule of law and judicial independence;

- Cohesion Policy Funds (22.6 billion), 6.3 billion of which were frozen through the rule of law conditionality mechanism, 12.9 billion were tied only to the implementation of judicial reforms, and 3.4 billion were blocked for non-compliance with horizontal enabling conditions (the mentioned anti-LGBTQ+ law, the law on academic independence, and the law on treatment of asylum seekers).

- Home Affairs Funds (223 million), 69.8 million of which are from the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund (AMIF), 102.8 are from the Border Management and Visa Instrument (BMVI), and 50.5 are from the Internal Security Fund (ISF).

Thus far, budgetary conditionality is potentially the most effective tool available. They stand out from other tools by moving procedures from the subjective realm of values to the objective realm of finance, thereby offering a clear method to illustrate how corruption functions. In addition, Recovery Plans (as the one mentioned above) primarily depend on states meeting their financial commitments, focusing on economic criteria rather than ambiguous values, which enhances their effectiveness. By combining budgetary conditionality with the milestones outlined in the Recovery Plans, the EU significantly boosts its ability to enforce the rule of law reforms among Member States.

Legal Workarounds

The EU has found another way to deal with Hungary’s blockages of financial aid packages to Ukraine. Ever since one of the first attempted blocks in December 2022, certain Member States have been seeking a way to bypass the necessity of unanimity and approve a package without Hungary’s consent. Back then, it was proposed that the €18 billion of aid was not covered by the EU budget as planned but instead distributed among individual Member States. In that case, a unanimous decision would no longer be required. However, Budapest ended up abandoning its veto against the package.

In June 2024, the EU once again came up with a workaround that allowed the release of up to €1.4 billion to purchase military aid for Kyiv. EU chief diplomat Josep Borrell explained that since Hungary abstained from an earlier agreement to allocate the proceeds from Russia’s frozen assets, it ‘should not be part of the decision to use this money.’

Hungary’s Response to the Measures

Orbán’s government appears reluctant to give up its power in favor of improving the rule of law and thus has been actively resisting any legal punishments by the EU. For instance, in 2022, the Hungarian Prime Minister repeatedly dismissed the whole of the EU and described ‘Brussels’ that ‘fulfills commands of a globalist elite’ as a threat to Hungary’s sovereignty.

Since the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Budapest has acquired new leverage against the EU. The Hungarian government has been actively employing its veto position to resist Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) decisions on the imposition of sanctions packages against Russia. For example, in February 2023, they insisted on the removal of specific individuals from the EU sanctions list. The blockage of the proposal to reduce the renewal period of sanctions from six to twelve months proved once again that Budapest values its influence over the EU. The goal of such resistance could be to negotiate some benefits, such as securing the release of certain funds. In December 2023, the EU released €10 billion in cohesion funds for Hungary. The official explanation by the Commission states that they noticed ‘guarantees to say that independence of the judiciary will be strengthened.’ However, it coincided with Orbán’s opposition campaign to block €50 billion in special funds to sustain Ukraine’s budget, as well as some other military aid packages. The convergence of these events poses a question of whether the EU was trying to appease Hungary to win its consent for Ukraine’s aid. Nevertheless, the Commission denied such accusations. In March 2024, the European Parliament decided to sue the Commission over a €10 billion payment to Hungary, arguing it breached the EU executive’s duty to safeguard taxpayers’ money from misuse.

summit at the European Council in Brussels on 26 October 2023. Photo: Ludovic Marin / AFP. Source: Telex

Why Does Hungary Stay?

In July 2024, the situation escalated to the point where the Polish Deputy Foreign Minister expressed doubts about Hungary’s membership in both the EU and NATO. Nevertheless, Orbán did not react. It appears that EU membership remains crucial for the Hungarian government despite the frequent criticisms of the EU and numerous disagreements with European values. This is primarily because Hungary’s unstable economy heavily relies on EU funds, making it unlikely for them to consider leaving the EU.

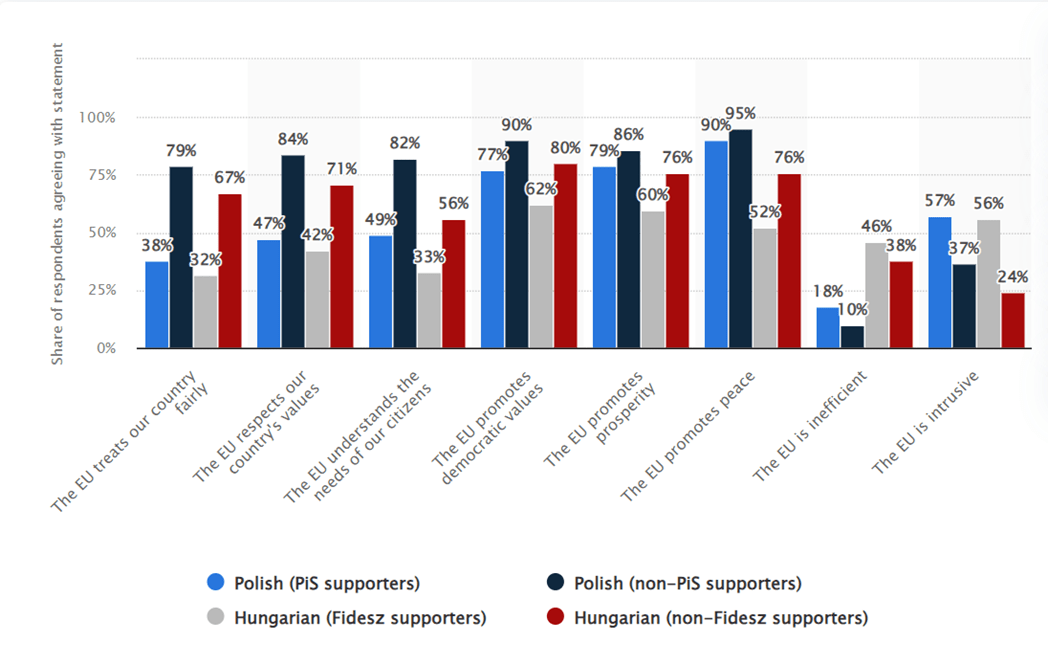

Even so, Budapest appears to use only those funds in its favor. Hungary leads in the number of investigations initiated by the EU’s anti-fraud agency, OLAF, regarding the misuse of EU funds. Additionally, research has indicated that EU funds have not consistently enhanced productivity – companies that received funding grew slower than those that did not. Hungarian citizens appear to understand that a significant portion of the funds was either embezzled or distributed among pro-government groups. Yet, most of them are still not willing to consider the idea of leaving the EU. According to the poll published by Statista Research Department in 2024, both Fidesz and non-Fidesz supporters mainly agree that the EU promotes prosperity – the figures amount to 60% and 76%, respectively. Even though only 32% of Fidesz supporters think that the EU treats their country fairly, around two-thirds of non-Fidesz supporters agreed with the statement. In general, there is a trend of criticism by those who vote for Fidesz and significantly more support from the non-Fidesz side.

by support for respective governing parties. 2024. Source: Statista

Another survey indicates that about half of Hungarians support closer integration with the EU, while 35% align with Orban’s sovereigntist view that Brussels should ‘give us the money and leave us alone.’ Among this group, 15% openly back a ‘Huxit’ (Hungary exiting the EU), although they remain a small minority, even among Fidesz voters. 73% of Hungarians are still in favor of EU membership, according to Eurobarometer data (2023).

Conclusion

Hungary has consistently violated EU legislation for more than ten years. In particular, there have been serious rule of law deficits; human rights and freedoms were not guaranteed to every Hungarian; asylum seekers were treated poorly and against international law. Budapest has also shown defiance of official EU policies by refusing to support multiple Ukraine aid and Russia sanction packages. The country continues to import Russian energy despite most Member States avoiding doing so.

To address these violations, the EU used a range of punitive mechanisms against Hungary. First, there is the Article 7 procedure, which has so far been successful in confirming a ‘clear risk of a serious breach’ of the EU law but hasn’t progressed further to adopting any concrete measures. Next, there are multiple financial instruments, such as the budget conditionality mechanism, which allows the Union to block part of the funding to Hungary, and infringement procedures, which require a Court of Justice ruling to impose such sanctions.

In essence, financial instruments have proved to be the most effective. Restricting access to funding appears to be an issue for Orbán’s government, considering his frustration over these measures and the fact that the Hungarian economy relies on EU funding. At the same time, it has also led to Budapest weaponizing its veto position and using it as political leverage to block the EU’s crucial decisions on Ukraine. Presumably, these actions aim to bargain for benefits, such as the release of some funds.

As Hungary is not planning to leave the Union anytime soon, the EU is only capable of exerting pressure on the Hungarian government through various legal instruments. As of now, around €30 billion of funds are frozen for Budapest. This is a great deal of money – it amounts to approximately 5% of Hungary’s gross domestic product in 2023. This gives the EU significant leverage of its own. If the procedures progress, Hungary will not only feel the economic consequences of its violations, but the second step of the Article 7 procedure will also suspend its voting rights in the Council. This would considerably limit Orbán’s ability to express his anti-democratic views and prevent him from further undermining fundamental European values.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations the authors may be associated with.