3 MB

Key Takeaways

- Scale and Documentation: Over 128,000 cases of Russian war crimes in Ukraine are documented, with extensive efforts by Ukrainian courts and international bodies to prosecute perpetrators.

- International Legal Action: The ICC has issued arrest warrants for top Russian officials, including Vladimir Putin, highlighting the international community’s commitment to accountability.

- Universal Jurisdiction: Countries like Germany, Lithuania, and Argentina are using universal jurisdiction to prosecute Russian war criminals, even without direct ties to the crimes.

- Special Tribunals: Various models for special tribunals are being considered to address the crime of aggression, with Ukraine opposing hybrid tribunals due to immunity issues.

- Technological Advancements: Platforms like WarCrimes.gov.ua and tools like AI and OSINT are enhancing evidence collection and documentation efforts.

- Civil Society Involvement: Ukrainian human rights organizations are playing a crucial role in documenting war crimes and supporting investigations.

- Historical Precedents: The principle of universal jurisdiction has been successfully applied in cases like the Rwandan genocide and the trial of Augusto Pinochet, setting important precedents.

- Challenges and Constraints: Universal jurisdiction faces barriers like varying national legislation and the potential for trials in absentia, but remains a critical tool for justice.

- Global Cooperation: International efforts are vital in prosecuting war criminals, reducing safe havens for perpetrators, and ensuring that justice is served.

Over 128,000 cases of Russian war crimes in Ukraine — each leaving countless ruined lives in its wake — have been documented in the Unified Register of Pre-trial Investigations. Yet, the law has already set its sights firmly on the Russian war criminals. With 530 charges filed by Ukrainian domestic courts, the ICC arrest warrants, including one against Vladimir Putin, the primary orchestrator of the war, charges against Russian war criminals issued by the United States, and ongoing war crimes investigations conducted by over 20 other countries, it is apparent that accountability can and should be pursued even before the full restoration of peace.The vicious cycle of impunity cannot exist forever. Ukrainian society strongly demands bringing the perpetrators to justice — throughout every level of the command hierarchy. However, the scale of the problem poses numerous logistical and legal challenges. Only through joint action and assistance from international partners can justice be restored. This article explores various avenues for holding perpetrators accountable, with a particular focus on the principle of universal jurisdiction and the ability of individual states to contribute to achieving justice for Ukrainian war victims.

I. Сore International Crimes: Legal Avenues for Prosecuting Russia and Its Leaders

By launching a full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022, Russia has demonstrated that massive human rights violations and blatant disregard for international humanitarian law constitute the official policy of the criminal Kremlin regime. The international community has swiftly exhibited its determination to work together to restore legal order. Shortly after the invasion, the International Criminal Court’s chief prosecutor, Karim Khan, based on the referrals from 40 State Parties, announced the commencing of investigations of “any past and present allegations of war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide committed on the territory of Ukraine since 21 November 2013.”

The Russian Federation has resorted to the commitment of heinous crimes against Ukraine, including the crime of aggression, war crimes, und crimes against humanity. Furthermore, according to the PACE resolution from 27 April 2023, Russian actions regarding the deportation and forcible transfer of Ukrainian children to Russia or temporarily occupied territories can be classified as a crime of genocide. Despite the non-binding nature of the resolution, it contains important political calls and is a step towards a legal investigation of the crime of genocide. Pursuant to the Rome Statute, the International Criminal Court has jurisdiction over the four gravest crimes of concern to the international community mentioned above.

The commission of the crime of aggression[1] essentially involves the highest political and military authorities of the state; in other words, it is a leadership crime. In accordance with the Kampala Amendments on the crime of aggression, the International Criminal Court is authorized to exercise jurisdiction solely over States Parties to the Rome Statute. This provision does not extend to Russia, as it is not a party to the Statute. Although Ukraine is yet to ratify the Rome Statute, it has twice accepted the court’s jurisdiction over atrocity crimes committed on its territory, with the second declaration from February 2014 being open-ended in nature. As a matter of fact, the ICC can also investigate the crime of aggression if there is a referral from the UN Security Council; however, the latter is paralyzed by the Russian veto power. This creates a major accountability gap regarding the crime of aggression.

Given that the ICC is not a feasible option in the prosecution of crimes of aggression perpetrated against Ukraine, discussions have been underway to establish a special tribunal that could bring to justice the highest officials, primarily Putin. The potential models for a future tribunal vary widely, including one created on the basis of an agreement between Ukraine and the UN with approval from the General Assembly, another established by a treaty under the auspices of the Council of Europe, and even a hybrid tribunal that would be integrated into the Ukrainian judicial system. And while so far, G7 States have been promoting the last option, Kyiv’s stance is principled — a hybrid tribunal has no room for discussion, as it will not be able to overcome the immunities of the so-called “troika” (the Russian president, prime minister, and the minister for foreign affairs). This position is crucial, as it underscores that the blood of the Ukrainian people stains not only the hands of the perpetrators but also the consciences of those who issue criminal orders.

Without underestimating the importance of finding a mechanism to investigate the crime of aggression, it is necessary to emphasize the important work of the ICC in investigating other core crimes. On 17 March 2023, the ICC issued arrest warrants against Vladimir Putin and Maria Lvova-Belova, the Russian Children’s Rights Commissioner, charging them with the illegal transfer of Ukrainian children to the Russian Federation. According to the Children of War initiative, more than 19,500 children have been deported by Russia since the start of the full-scale invasion, though the actual numbers can be higher.

[1] In accordance with Article 8bis (1) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, it is “the planning, preparation, initiation or execution, by a person in a position effectively to exercise control over or to direct the political or military action of a State, of an act of aggression which, by its character, gravity and scale, constitutes a manifest violation of the Charter of the United Nations.”

Children have been extensively instrumentalized by the Kremlin propaganda: under the guise of “rescuing” Ukrainian children, Russia has set up a mafia-like criminal network consisting of multiple entities, including the Russian Orthodox Church, that is engaged in deporting, re-educating, and indoctrinating these children with “Russian traditional values.”

A year later, on 5 March 2024, the ICC issued two further arrest warrants against two top-level Russian military commanders responsible for the war crimes of attacking civilian objects and causing excessive harm to civilians in violation of the Geneva Conventions, to which Russia is still a party. The number of arrest warrants increased on June 24, 2024, when the ICC deemed the evidence sufficient to target Sergei Shoigu, the former Russian Minister of Defence, and Valery Gerasimov, the Chief of the General Staff of the Russian Armed Forces. They are individually responsible, among other offenses, for the Russian army’s missile strikes against Ukraine’s electricity infrastructure. This implies that if the suspects are within the territory of one of the 124 State Parties to the Rome Statute, they will be promptly arrested and surrendered to the ICC — an important step significantly reducing the number of safe havens for individual war criminals.

Russian war crimes can also be investigated and prosecuted in Ukrainian domestic courts, as well as in other countries, opening more prospects for justice.

II. Documenting War Crimes: No Perpetrator Will Go Unnoticed

While holding the Russian top leadership accountable might take years because of the need to prove their criminal intent, Ukraine focuses on investigating war crimes committed by “direct perpetrators.” According to the Prosecutor General of Ukraine, Ukrainian law enforcement is currently investigating 128,000 war crimes. Such a large number of cases would pose a challenge to any system attempting to adopt a human-centered approach to avoid re-traumatizing war crime victims. Moreover, Ukraine is dealing with a wider range of war crimes that have not been subject to prosecution before, such as crimes against the environment and cyberattacks.

Russian illegal actions in Ukraine are not sporadic — there is a clear pattern of grave human rights violations, including but not limited to killings, deprivation of liberty, torture, sexual violence, enforced disappearances, attacks on civilian infrastructure, and extrajudicial executions. By denying access to places of detention of Ukrainian POWs and illegally detained civilians, Russia continues to ignore the mandate of the ICRC and the relevant UN agencies.

In order to unite the efforts of state authorities and civil society, Ukraine launched special platforms for the public to report war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by Russia in Ukraine, such as WarCrimes.gov.ua and Svidok. Modern technologies are relatively new but extremely helpful in the process of evidence collection: for example, Palantir is used for analyzing vast quantities of data, and Microsoft is employed for voice recognition of criminals allegedly calling for genocide. The use of AI and OSINT tools allows for real-time collection of evidence and unveils serious human rights violations, giving hope that no perpetrators will be able to go unidentified.

A large share of work in documenting war crimes is carried out by Ukrainian human rights organizations that united their efforts by founding the “Ukraine. 5 AM Coalition” shortly after the full-scale invasion. Among the participants are ZMINA, Media Initiative for Human Rights, Truth Hounds, Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, and other experienced organizations. Their methodology includes organizing field missions to de-occupied areas, directly engaging with victims and witnesses, and integrating information gathered from open sources. Their findings significantly enhance the investigations carried out by the ICC, Ukrainian domestic courts, and potentially foreign courts that may initiate cases under the principle of universal jurisdiction.

III. Universal Jurisdiction: Justice Without Borders

The origins of universal jurisdiction date back to the time when pirates were considered the greatest enemies of mankind — states could punish them regardless of nationality. Today, the international community recognizes that certain crimes are of such magnitude that they pose a threat to the entire global order and thus cannot be tolerated. These include war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and torture.

Taking on its modern shape after the Second World War, the principle gained significant recognition in the 1948 Genocide Convention, the 1949 Geneva Conventions on the laws of war, the 1984 Convention against Torture, and was reinforced through several other human rights treaties. The principle postulates that any state’s national authorities may investigate and prosecute individual perpetrators of international crimes regardless of the location of the alleged crime and irrespective of the nationality and residency of the perpetrators and victims. In other words, without having any “link” to the crime committed, states might still prosecute it in the name of safeguarding universal values.

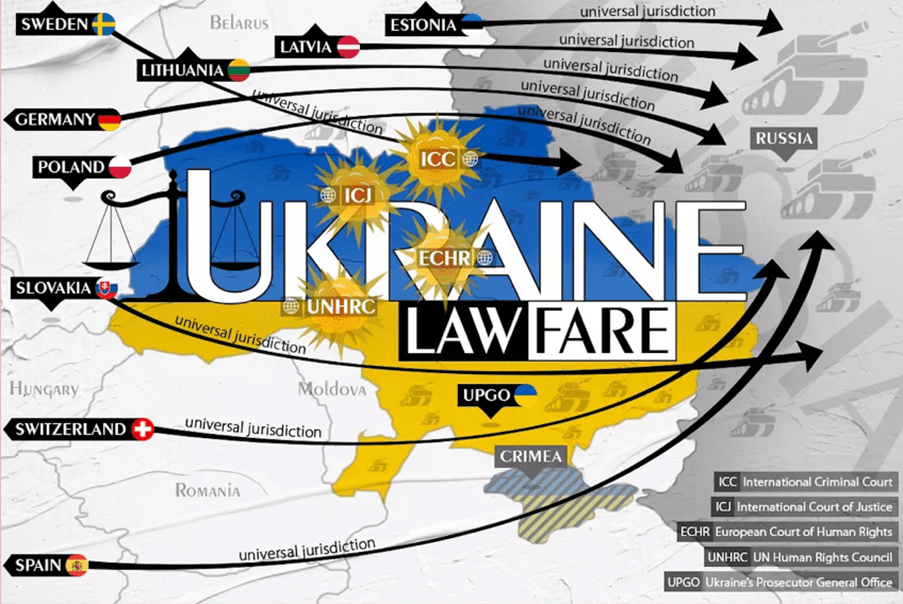

To date, around 150 states have incorporated universal jurisdiction into their legislation to some extent, as Amnesty International reports. The involvement of various systems of jurisdiction, especially in countries where survivors of Russian war crimes as well as witnesses are currently residing, is extremely important for Ukraine. Several states have already launched preliminary universal jurisdiction investigations, starting from Germany in early March 2022, and followed by Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Sweden, Spain, Polen, Slovakia, France, Norway, and Switzerland. Some of these cases are not aimed at specific individuals but are rather carried out for the purpose of collecting evidence and patterns of war crimes. The most recent case of submitting a legal complaint at a foreign court (outside of Europe and the US) took place on April 15, 2024, in Argentina: The Reckoning Project filed a lawsuit on behalf of a Ukrainian man tortured by the Russian occupiers. If Argentina, which already has extensive experience in fighting for justice through universal jurisdiction, decides to open an investigation, it will once again highlight the fact that the safe harbor for Russian criminals is shrinking.

One of the most prominent cases of the use of universal jurisdiction includes the trials of those responsible for the 1994 Rwandan genocide. In 2001, Belgium convicted and issued sentences ranging from 12 to 20 years against four Rwandan citizens, and in 2010, Finland sentenced Francois Bazaramba, a former Rwandan pastor, to life in prison for his involvement in the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

Just recently, on 15 May 2024, the top criminal court in Switzerland sentenced former Gambian interior minister Ousman Sonko to 20 years for committing crimes against humanity, including killing, torture, rape, and unlawful detentions. Previously, he had left Gambia and sought asylum in Switzerland. The conviction of such a high-ranking official marks an unprecedented level of success for universal jurisdiction in Europe. As journalist Madi MK Ceesay stated, “the trial demonstrates that no matter what, the long arm of justice can always catch the perpetrator,” reports The Associated Press.

An important case relating to the immunities of the state leaders and universal jurisdiction is the case of Augusto Pinochet. Though he was not ultimately extradited, his arrest in London in 1998 following the arrest warrant issued by a Spanish court demonstrates the implementation of universal jurisdiction and sets an important precedent. Despite claims of presidential immunity from prosecution, the UK’s highest court ruled that such immunity does not extend to grave crimes like torture, extrajudicial killings, and forced disappearances.

IV. Barriers and Benefits of Universal Jurisdiction

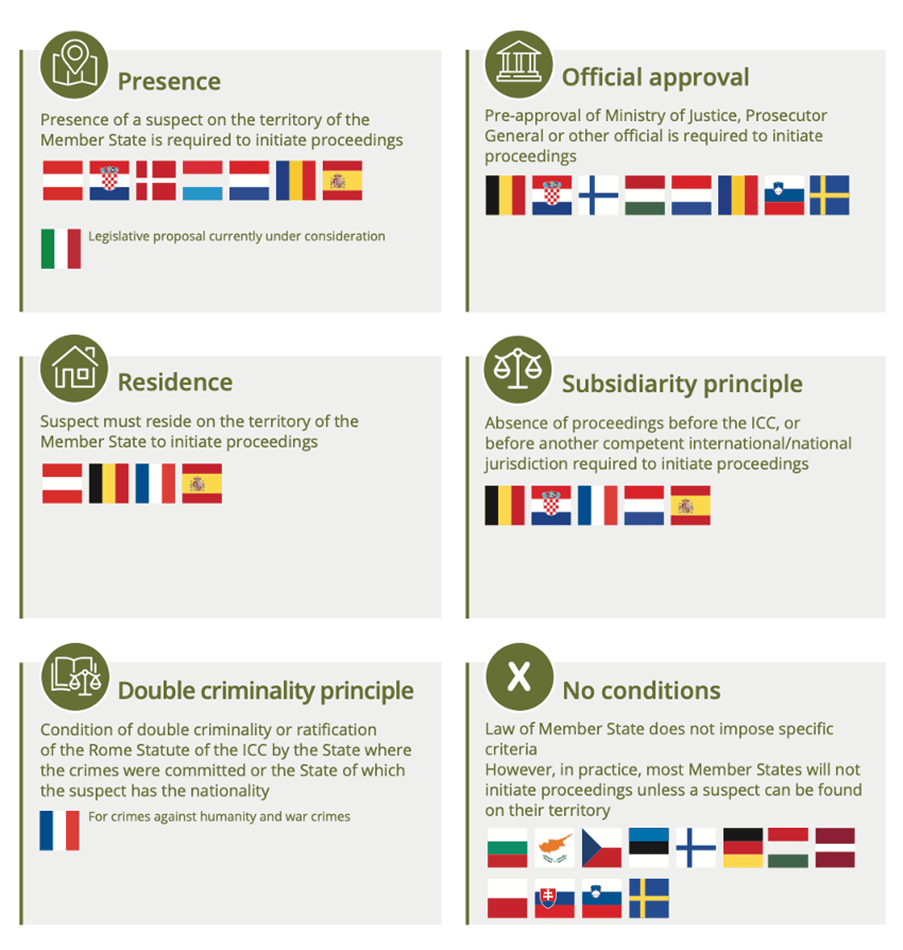

While such issues as the establishment of a special tribunal necessitate international consensus, the decision to resort to universal jurisdiction rests with individual countries, depending on their political will and the intricacies of the national legislation. It is worth focusing on the latter aspect, as countries vary in their interpretation and establishment of the conditions for universal jurisdiction. Indeed, some countries do not even require complaints from victims, and legal proceedings can advance in case there is sufficient evidence. Conversely, in other systems, even the presence of victims does not allow for the launch of the investigation due to various constraints.

Universal jurisdiction can be categorized into two types: absolute and conditional.

Under absolute universal jurisdiction, prosecution of the most horrendous crimes can be initiated regardless of where the crime was committed and what nationality both the victim and the perpetrator are. In Europe, several states exercise this type of universal jurisdiction, with Germany being the most prominent example. In November 2021, it became the first country to convict a member of the Islamic State (IS) for genocide against the Yazidis, an ethno-religious minority in Iraq, and crimes against humanity. Furthermore, in January 2024, a German court sentenced a former Syrian colonel to life in prison for committing crimes against humanity. Neither of them had any relation to Germany.

Still, the majority of states can only exercise universal jurisdiction if there is a stronger link between the alleged crime and the state itself. For example, Austria, Spain, and Switzerland can initiate criminal proceedings only if the suspect is present in their territory. France invokes universal jurisdiction solely if the victim is its national or the alleged perpetrator is a French citizen or resident. Before 2022, the federal war crimes statute of the United States allowed for the investigation of war crimes committed anywhere, provided that either the victim or suspect is a member of the U.S. Armed Forces or an American national.

Three months into the Russian brutal invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. Justice for Victims of War Crimes Act (JVWC) was introduced and subsequently, on January 5, 2023, signed into law by President Biden. It enables prosecution of alleged war crimes committed by foreign nationals overseas if the latter are found in the territory of the US. This decision, though having no retroactive effect, lays the groundwork for the United States to bring to justice those committing war crimes against the Ukrainian people.

Another constraint for the universal jurisdiction system is the potential of conducting trials in absentia, that is, without the physical presence of the defendant. Many countries see absentee trials as problematic due to the challenges they pose for ensuring the right to a fair trial. Unlike in Ukraine, which allowed for the possibility of trials in absentia back in 2014, this procedure is impossible in many states, though no international treaty explicitly prohibits exercising jurisdiction in absentia. In aiming to achieve justice as fast as possible, Ukraine still ensures the presence of a defense lawyer for the accused in accordance with the European Convention on Human Rights. Of course, the majority of these criminals are within Russian territory, and it is highly unlikely that Russia will agree to extradite its citizens. Nevertheless, such cases are intended to send a clear message to perpetrators that their freedom of movement is significantly restricted, accountability is inevitable, and the threat of prosecution will loom over them forever. Moreover, it provides victims with a sense of acknowledgment and validation. This aligns with one of the legal maxims: “Justice delayed is justice denied.”

There are reasons to believe that the international community will play a crucial role in aiding victims in their pursuit of justice. In December 2023, the U.S. Department of Justice filed charges against four Russian soldiers for unlawful confinement, torture, and inhuman treatment of an American citizen during the war in Ukraine. The Office of the Prosecutor General of Ukraine noted that “it was the first case of accountability for war crimes committed during the Russian aggression under the jurisdiction of foreign countries.”

In regards to Europe, in October 2023, three cases concerning war crimes of the Russian soldiers were filed in Germany by the NGO named “Clooney Foundation for Justice.” The cases are related to the missile strike near Odesa that resulted in the deaths of 22 civilians, the unlawful detention and execution of 4 men in the Kharkiv region, and a sequence of executions and sexual violence committed near the Kyiv region in early 2022. When German authorities deem the evidence convincing, they can launch a criminal investigation, which might further lead to the issuance of warrants for the suspects. Through Europol and Interpol systems, the enforcement of these arrest warrants can extend well beyond Germany.

Moreover, according to the federal justice minister of Germany, in the procedure regarding targeted firing at fleeing civilians in Hostomel, five Russian shooters have already been identified. France has also initiated an investigation after the France-Presse journalist was killed by a Russian rocket in the Donetsk region, and Lithuanian law enforcement is investigating the killing of the Lithuanian filmmaker in Mariupol along with other violations of international humanitarian law.

Conclusion

Russian heinous crimes committed in Ukraine have prompted the international community to explore various paths towards bringing Russian top leaders and subordinate offenders to justice. The International Criminal Court and potential special tribunals are certainly key mechanisms, but the Ukrainian system needs more immediate assistance and relief. Hence, it is crucial that other countries utilize universal jurisdiction mechanisms for prosecuting criminals, gathering evidence for subsequent judicial proceedings, and ensuring that victims feel validated in their experiences.

In the Ukrainian situation, the international community has many avenues for evidence collection, given that the war is ongoing. There are no obstacles like recreating age-old historical events and gaining access to witnesses. Many actors are involved in documenting Russian war crimes and are willing to share evidence — from national authorities to civil society organizations — and society’s expectations are high, with over 70% of people demanding that crimes be prosecuted.

Administering international justice is an intricate, time-consuming, and resource-intensive process, impeded by various inherent challenges. Nevertheless, universal jurisdiction can be an effective complement to international justice mechanisms of holding perpetrators of war crimes, genocide, and crimes against humanity accountable, and sending a signal that the cycle of impunity will eventually be broken.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations the authors may be associated with.