2 MB

Key Takeaways

- NATO’s Future at a Crossroads: Trump’s reelection amplifies concerns about U.S. security commitments, pushing Europe to consider greater independence in defense and burden-sharing within NATO.

- Defense Spending Disparities: While Eastern flank countries lead in defense spending, public resistance in many European nations hinders progress toward stronger security budgets.

- Modernizing Deterrence: NATO’s shift from “deterrence by retaliation” to “deterrence by denial” requires significant investments in troop readiness and advanced capabilities to counter the Russian threat.

- Strategic Autonomy Challenges: With 63% of military equipment currently imported from the U.S., the EU is launching a €1.5 billion Defense Industrial Strategy to localize arms production and reduce dependency on American supplies to address growing security needs.

- Nuclear Deterrence Debate: France’s proposal to extend its nuclear umbrella to other European nations reflects growing uncertainty about U.S. support, though political and logistical hurdles remain significant.

- Urgency for Action: Europe’s security environment demands immediate political courage, collective decision-making, and effective communication with citizens to navigate rising threats and geopolitical instability.

U.S. commitment to European security has been a topical issue throughout the 2024 U.S. presidential election campaign, fueling much debate among policymakers, analysts, scholars, and media. The reelection of Donald Trump on November 5 has only intensified the talks about the future U.S. security commitment to Europe. Main concerns are raised by the controversial nature of some of his remarks about NATO and his plans for a rapid end to the Russo-Ukrainian war. Some of the expressed opinions worry about the detrimental outcomes of the next administration’s decisions for Europe. Others anticipate that European member-states will benefit from the future developments, should they unite and put enough effort into adjusting to any changes in U.S. global strategy. Although no real plans of the coming administration are known yet, this paper seeks to assess the predictions of experts and politicians, the future American leadership’s strategy in Europe, and the consequences that certain decisions may bring for the geopolitical and security situation on the continent.

Decades of dependence on U.S. security assurances and military presence in Europe helped the continent overcome the destruction of WW2 by focusing primarily on economic integration. Yet the EU’s efforts to spill the integration over the political and defense sphere proved unsuccessful. The potential loss of sovereignty in foreign and security policy, highly valued by the EU member-states, additional financial spending, and possible overlaps with NATO have stood in the way of integration. Their defense capabilities have been further reduced after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, showcasing their readiness to integrate Russia into a Western system through trade and economic relations. Apparently, this strategy did not live up to the hopes placed on it.

What seems clear is that the Trump administration won’t be able to withdraw the U.S. from NATO unless the Senate approves it. According to the 2024 National Defense Authorization Act, two-thirds of the Senate should consent to a decision to leave NATO. Nevertheless, Trump’s rhetoric has put significant pressure on NATO member-states since his first tenure as U.S. President.

Defense Spending

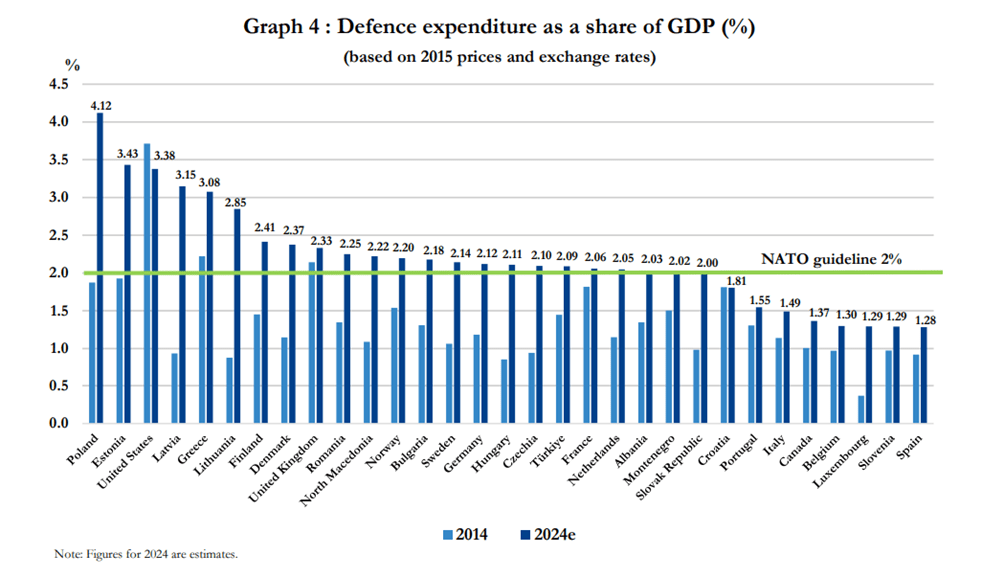

Donald Trump has made his position clear about burden-sharing within the Alliance, frequently calling on European member-states to reach the defense spending target of 2%. In February 2024, he even stated that he would “encourage” Russia to target any NATO allies he believes have failed to fulfill their financial commitments. In this regard, Trump’s approach to NATO is described as transactional. Notably, 23 out of 32 countries are expected to spend at least 2% of GDP by the end of 2024. Poland is leading among those meeting this financial obligation, contributing 4.1% of its GDP to defense. Estonia and the U.S. follow it with 3.4%. The Eastern flank countries demonstrate their prudent perception of the Russian military threat, having reached the NATO guidelines and aiming for a further increase.

Some suggest that the existing threat from Russia requires the NATO members to raise their defense spending to 4%, which seems impossible for most allies in the coming years. There is also speculation that Trump may demand that allies agree on increasing the defense expenditure to 3% at the 2025 NATO summit in the Netherlands.

More than a decade ago, U.S. Defense Secretary Robert M. Gates called NATO “a two-tier alliance,” divided into those willing to contribute to transatlantic security both financially and militarily and those mostly benefiting from security guarantees and reluctant to take on the burden of alliance commitments. This idea has recently been reinforced. Some analysts and former Trump administration staff, including Keith Kellogg, national security adviser to Vice President Mike Pence, proposed turning NATO into a “tiered alliance,” where member-states would be split based on their defense spending: those that comply with the NATO 2% guideline would enjoy the security guarantees while the rest would be deprived of the same protections.

An increase in European NATO members’ defense budgets largely depends on the leaders’ political courage and public support. The latter varies across Europe. While some states’ population expresses support for strengthening their country’s security and defense, such as Bulgaria (almost 60%), Sweden (55%), Albania, and Norway (around 50%), most citizens of the others would rather prefer their governments cut defense spending. These include the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Italy, Luxembourg, Estonia, Croatia, etc., where only approximately 30% of the population wants their countries to spend more. The primary reason for such statistics lies in people’s interest in domestic issues their countries encounter. However, given the instability of the European geopolitical environment, alongside a direct threat posed by the Russian Federation, the governments have to seek ways to communicate their security worries with the public.

NATO’s Deterrence and Defense

The 2022 Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine has provoked fundamental changes to NATO’s defense and deterrence strategy. Since 1991, NATO’s defense has mostly been based on deterrence by retaliation. This essentially means convincing an aggressor that NATO will strike back in case of an attack. Yet the main flaw of this strategy is its responsive nature, which can mean an inevitable loss of territories. After the 2022 Madrid Summit, a new NATO Strategic Concept has revitalized deterrence by denial, responding to a new geopolitical reality and security threats to the Alliance. Its main objective is to deploy sufficient forces to prevent an aggressor from an invasion due to the costs or risks that outweigh its benefits from such an action. Both strategies constituted NATO’s pillars of deterrence during the Cold War. The latter has regained relevance since the Russo-Ukrainian war returned Europe to the reality of large-scale conventional warfare.

As a part of the 2022 Strategic Concept, a new NATO Response Model has been introduced, increasing the number of high-readiness forces from 40,000 to 300,000 troops, available for deployment within a month, with an additional 500,000 ready for deployment within 6 months. However, implementing the “deterrence by denial” strategy requires a conventional force balance with an adversary. While it was relatively achieved during the Cold War era, the current situation shows that the Alliance needs to continue building up its troops in order to deter the Russian threat.

Furthermore, European NATO allies have to upgrade their air, land, maritime, cyber, and space capabilities, which involves the deployment of defense industries, investment in cutting-edge technologies, advanced military training, and strengthened interoperability among member states.

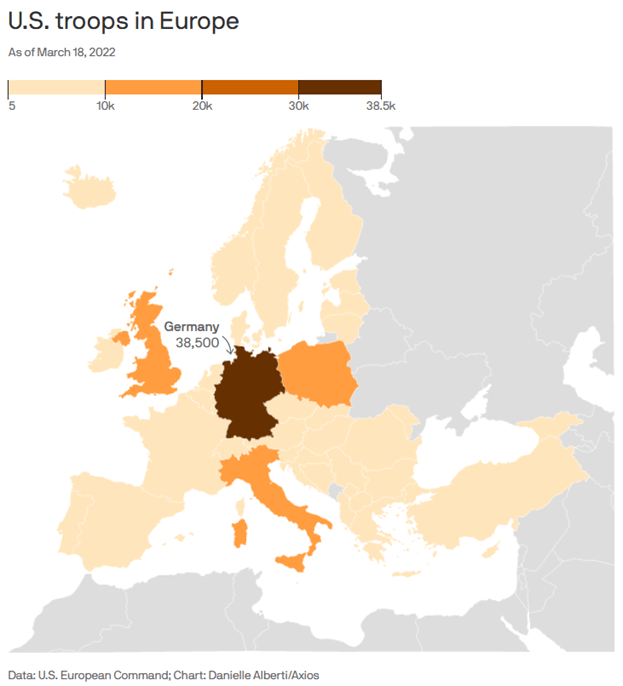

U.S. Military Presence in Europe

Considering the current developments, Donald Trump’s intent to reduce the U.S. security commitment to Europe and its role within NATO raises questions about the future of U.S. troops stationed on the continent and potential alternatives for their presence. At present, there are approximately 100,000 U.S. troops stationed in Europe. Notably, in response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Pentagon deployed 20,000 additional forces across the continent. A drastic decrease in U.S. defense support for Europe should encourage it to take greater responsibility for its security.

Certain European states, such as Germany and Italy, are considering reintroducing mandatory conscription. 9 EU countries already have military service for their citizens: Cyprus, Greece, Austria (non-NATO country), Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland, Sweden, and Denmark. This topic has been quite sensitive for the continent, widely known for its pacifist public sentiment, commitment to peacekeeping and humanitarian initiatives, and relatively peaceful existence over the past decades. For some states, this issue is even more intricate since it will require amending their constitutions. Given the rise of populist political parties in Europe, parliaments may face a lack of support for such initiatives, potentially turning the reinstatement of conscription into a casualty of political contention.

However, the harsh reality of the contemporary security environment in the European region suggests that the lack of military-qualified manpower threatens to undermine NATO deterrence and defense.

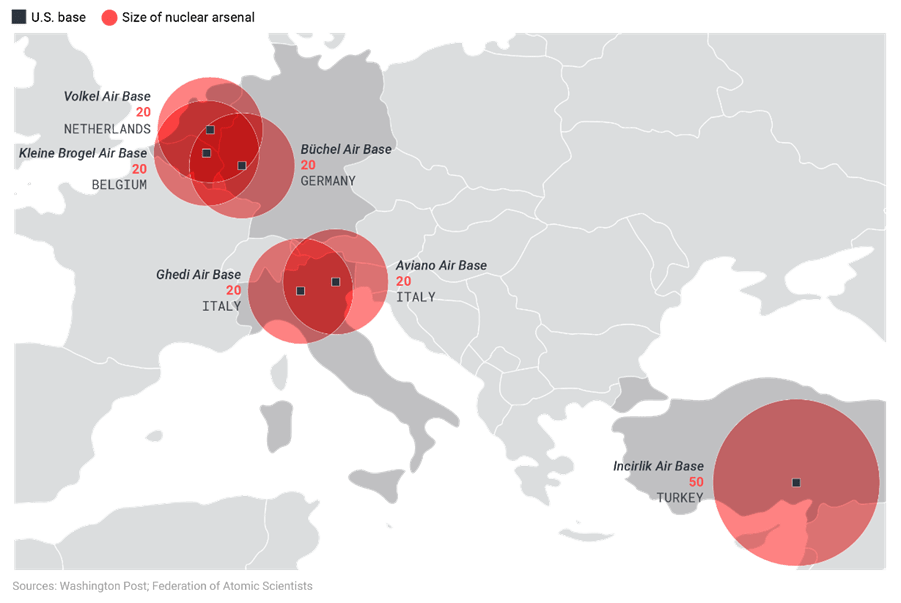

Nuclear Umbrella

One of the potential scenarios for the future of NATO proposes the U.S. maintaining its nuclear umbrella in Europe while leaving conventional forces to the discretion of European NATO members. While some argue that Trump is unlikely to withdraw America’s nuclear deterrent from Europe, certain European leaders have begun initiating some discussion on this matter.

The UK and France are the only European NATO members possessing nuclear arsenals. Emmanuel Macron has called for strengthening the continent’s nuclear security pillar by extending the French nuclear deterrent to the rest of Europe due to the concerns surrounding future U.S. security commitments within NATO. While some believe that British and French arsenals are not enough to ensure the nuclear deterrence of the Russian Federation, others assume that nuclear restraint doesn’t depend on the quantitative characteristics of an arsenal. The enormous destruction that the usage of nukes can lead to should already discourage an aggressor from launching a strike against a nuclear country or alliance. Therefore, when considering the UK’s and France’s involvement in the European nuclear umbrella, political courage and collective decision-making are the key factors shaping the Alliance’s ability to deliver an adequate response. Yet despite their NATO commitments, they hold exclusive control over their nukes. For this reason, further discussions and enhanced cooperation among the NATO allies are crucial for any significant changes. Equally important is the political will in Paris and London to share nuclear decision-making.

Despite some countries’ efforts to raise this topic, the majority of states continue to rely on the U.S. nuclear umbrella, as its withdrawal is believed to be unlikely even under the Trump administration due to its importance to U.S. national security.

Defense Industry in Europe

Another vital problem that Europe has faced in light of war close to its Eastern borders is low efficiency, underfunding, and overall vulnerability of the European defense industrial production and dependence on U.S. weapon supplies. For instance, between February 2022 and June 2023, 63% of the military equipment imported by European countries came from the United States.

It’s worth mentioning that while Europe’s dependence on U.S. arms supplies was revealed, the United States has significantly benefited from the rising need for weapons in Europe and Ukraine. Not only has the country increased its global role as an arms supplier, but it has also resumed the active work of its weapons production enterprises. By supplying Europe, including Ukraine, and other allies worldwide with arms, it started replenishing its own stocks with more sophisticated munitions.

Should Trump be willing to cut U.S. support for Ukraine, some argue that Europe should take over the financial expenditure to purchase weapons for Ukraine from the U.S. This is primarily explained by the fact that the total GDP of the EU and European countries exceeds Russia’s GDP by more than fivefold. This also fits into the narrative Donald Trump and his supporters have been leveraging throughout the presidential election campaign, which consisted of the fact that Europe should take on the financial burden of supporting Ukraine since its security depends on the country’s success in the first place. Considering Europe’s long-term interests, ramping up its defense industrial production is pivotal for its security autonomy from the U.S.

Common security and defense have long been overlooked by European leaders and consistently undermined by individual states in Europe. Interestingly, the EU’s treaties prohibit allocating its funds for military purposes. The urgent necessity to provide Ukraine with ammunition led the EU states to understand that the stocks should be replenished and the production needs to accelerate and increase in scale. Therefore, in 2023, the European Commission initiated the EU’s Defense Industrial Strategy, intending to provide long-term funding and encourage the development and procurement of defense projects on the EU’s territory. One of the most important goals of the strategy is to ensure that the EU countries allocate at least half of their defense procurement budgets to products manufactured in Europe by 2030. To start implementing the Strategy, the European Commission has proposed the European Defence Industry Programme, under which €1.5 billion in financial support from the EU budget will be provided to fund defense industry projects between 2025 and 2027. While this is already a big step forward, the negotiation process is very protracted, especially when it comes to funding. This may affect any initiative, once again showing the need for changes to respond faster and more effectively to current challenges.

But are the European arms manufacturers ready to partially replace the supplies coming from the U.S.? Geographically, three of Europe’s top ten aerospace and defense companies are headquartered in the United Kingdom, three in France, and the rest in the Netherlands, Germany, and Italy.

Deutschland

In this regard, Germany is worth mentioning. After German reunification, the country’s defense industry contracted by as much as 60%. Nevertheless, Germany has the potential to become one of the key arms suppliers in Europe. Rheinmetall and Diehl Defense are major German contractors that have already significantly expanded their production due to increased demand. Despite the Russian threat, the German government is still delaying the decision-making process on revitalizing the German defense industry, on which the future of European security depends to a large extent.

Sweden

Prominent for its decade-long neutrality, Sweden had to ensure its own security, especially given its geographic location. Prioritizing security has created the conditions in which Sweden has become one of Europe’s leading states in military technology, manufacturing, and air power. And this makes it a great asset for NATO after joining the Alliance in 2024. The Swedish defense industry is one of the largest in Europe, manufacturing some of the most sophisticated types of arms. Apart from Sweden’s ability to boost NATO with its defense industry, the Alliance can also significantly benefit from Swedish technological capabilities. Its high-tech has enjoyed years of considerable funding and can compete on a global level now. Considering Chinese technological advancement, Sweden can strengthen NATO by contributing its technological know-how to deter Russian and Chinese hybrid and cyber threats.

Conclusion

Judging by the facts, European security autonomy from the U.S. is unlikely to be achieved shortly, considering long-term American security commitments to NATO and Europe lagging behind in key areas such as the defense industry, aligning defense budgets to existing challenges, and lack of political courage and public awareness of the necessary changes. However, European security has reached a point where the continent’s future depends on political will to take on responsibility and address external threats while navigating domestic discontent and instability. No matter the outcome of the Russo-Ukrainian war, the political developments of the recent decades have shown that the Russian threat is to remain in Europe, while other additional challenges are looming on the horizon.

Despite the U.S. reorientation toward the Indo-Pacific region, Europe remains the key American ally, supporting the U.S.-led international world order and, what’s more important, facing the same adversaries willing to challenge their democracy, open economy, and the rule of law. Even though the Trump administration is likely to pursue a transactional approach toward the U.S. allies, Europe represents vital support for the U.S. efforts to diminish challenges to the existing international system. The benefits of this partnership should be a key incentive for its preservation. But Europe has to work toward ensuring its own security.

Disclaimer: The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations the authors may be associated with.