1 MB

China’s (In)convenient Ambiguity and Deteriorating Image

The Russian invasion of Ukraine stands out as the largest conflict in Europe since World War II, both in scale and intensity. Its far-reaching consequences extend beyond the borders of Ukraine and Russia, affecting global markets with rising prices, disrupted supply chains, and food insecurity. Naturally, this war has been a source of anguish for many in the international community, ranging from major powers to fragile states desiring a swift end to the conflict. Consequently, various suggestions and positions have emerged regarding a political resolution to this armed confrontation. Mediation efforts to support peace talks between Ukraine and Russia have been offered by actors such as the UN, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Israel, the Vatican, and Iraq, among others. However, the lack of a more proactive role by the People’s Republic of China, one of the key global players, has prompted curiosity and speculation. Furthermore, the discussion of whether China and Russia will form an alliance in its traditional sense pushed Western politicians to suggest China could play a major role in establishing peace by exerting pressure on the Kremlin to withdraw its troops and stop the invasion.

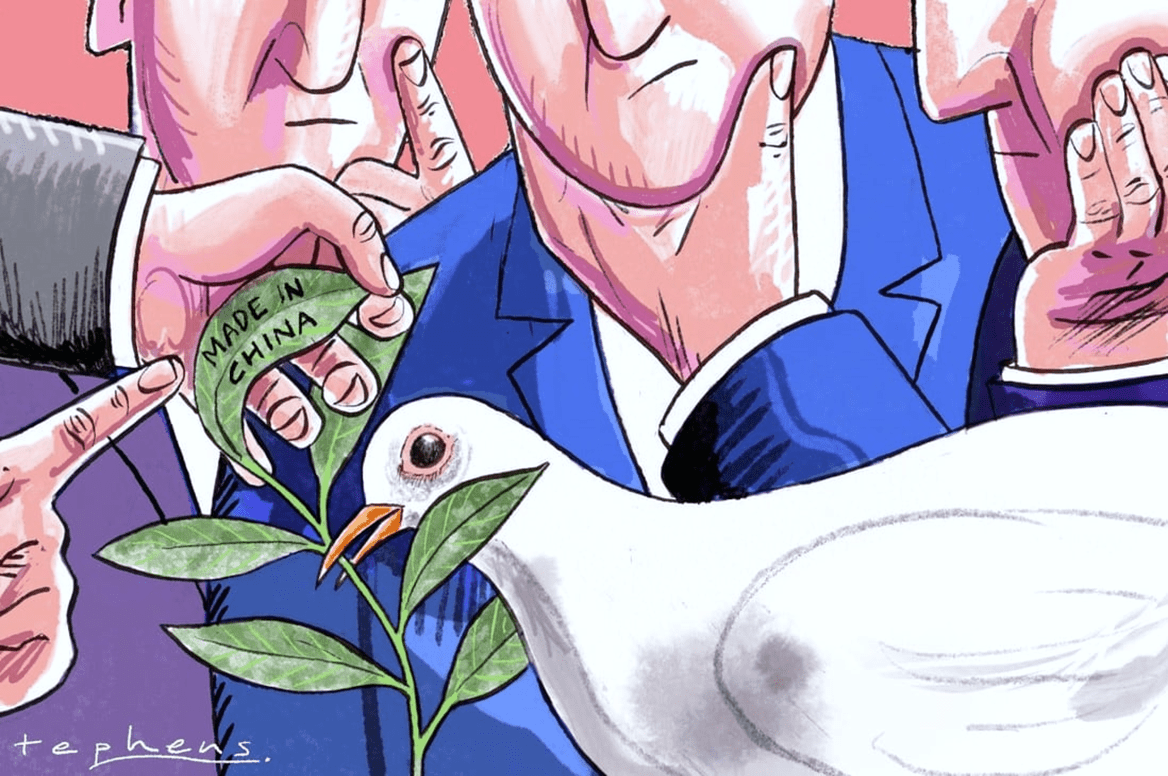

It took Beijing a considerable amount of time, precisely a year since the full-scale Russian invasion, to contemplate its stance on the war. From the initial days of the attack, PRC claimed a neutral position, which allowed for flexibility and maneuverability in alignment with its national interests. This Chinese perspective on the war has been criticized by many, particularly in the West, who perceive China as hypocritical.

China has derived certain benefits from its ambivalent position and a previously signed declaration of “no-limits friendship” with Russia, which has enabled it to take advantage of low prices for Russian goods, particularly oil and gas, thereby compensating for Russian losses due to sanctions. It also allowed Beijing to find another spot for criticism of the US-led liberal international order, therefore ramping up the ideological contestations between China and the United States. It also joined certain Asian, African, and Latin American countries with alternative stances on the Russian war against Ukraine potentially reaching their support for its position. PRC got an opportunity to exercise its influence on these countries and regions, especially aiming to crack the US framing of the wider conflict between democracies and autocracies. China has also shown diplomatic support for Russia, including its refusal to endorse any United Nations General Assembly resolutions condemning the attack on Ukraine and the attempted illegal annexation of Ukrainian territories. The Chinese framing of the invasion as a “crisis in Ukraine,” coupled with its anti-Western rhetoric that aligns with Russian propaganda, raises concerns among Western officials and PRC’s neighboring countries.

Additionally, China has faced criticism for its perceived manipulation of international law and the divergence between its stated fundamental principles, such as respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, and its reluctance to label Russia as an aggressor. The call for China to play a significant role in ending the war and exert pressure on the Kremlin has been repeated, particularly in the West. Consequently, China’s image has suffered a decisive blow due to its “neutral stance” on the conflict. Previous factors such as China’s unwillingness to openly investigate the causes of the COVID-19 pandemic, its vaccine diplomacy, allegations of espionage and intellectual property theft, Chinese loans and debt traps, and human rights violations in Hong Kong and Xinjiang have further contributed to the deterioration of China’s image.

Furthermore, China’s image has worsened due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, as it finds itself grouped among authoritarian powers, including Russia, which appears to pursue revisionist foreign policies and threaten Taiwan through military maneuvers around the island. China’s failure to criticize Russia for its actions in Ukraine and the numerous war crimes committed by Russian troops has further undermined its image, leading to furious reactions from Western political figures. Moreover, concerns arose during Xi Jinping’s visit to Moscow and his support for Vladimir Putin’s reelection in 2024, particularly in light of the International Criminal Court issuing a warrant for the arrest of President Putin and his Commissioner for Children’s Rights due to the forced deportation of children from Ukraine to Russia, where Russian families subsequently illegally adopted many.

Critics argue that China’s so-called “neutrality” essentially sides with Russia. The only positive pressure exerted by the PRC so far relates to the unacceptability of using nuclear weapons.

After a year of ambiguity, China finally presented its peace proposal and offered mediation efforts, which was quite different from what many in the West had anticipated. This has sparked intensive debates regarding China’s delayed delivery of the so-called “peace plan” and raised questions about Beijing’s suitability as a mediator between Ukraine and Russia.

To comprehend why China proposed diplomatic services a year into this brutal war and why this plan, or rather a position, remains vague, one must examine the broader context of China’s actions, considering domestic factors and external influences. To grasp Beijing’s maneuver properly, one must consider the continuity of Chinese foreign policy and strategic culture, its guiding philosophical principles, historical factors, the Chinese interpretation of diplomacy and international relations, and its vision of China’s status and role within the global system. Of particular interest are the key figures within the People’s Republic of China, especially Xi Jinping and his “diplomatic thought,” as he envisions the PRC assuming a more prominent and significant role in international affairs.

Decoding Chinese Diplomacy: Self-Perception, Principles, and Beijing’s Vision for International Relations

Before delving into Chinese peace proposals and examining Beijing’s potential as a mediator, it is crucial to understand the fundamental principles of China’s foreign policy and how China perceives its role in international affairs. Throughout history, China had believed in its central role in the world, even during ancient times when it lacked a complete understanding of other powers that could rival it. According to Chinese belief, their civilization was the only true one, and they welcomed outsiders to their land with the hope of transforming them, though without insisting on it.

Chinese exceptionalism as a reflection of traditional beliefs

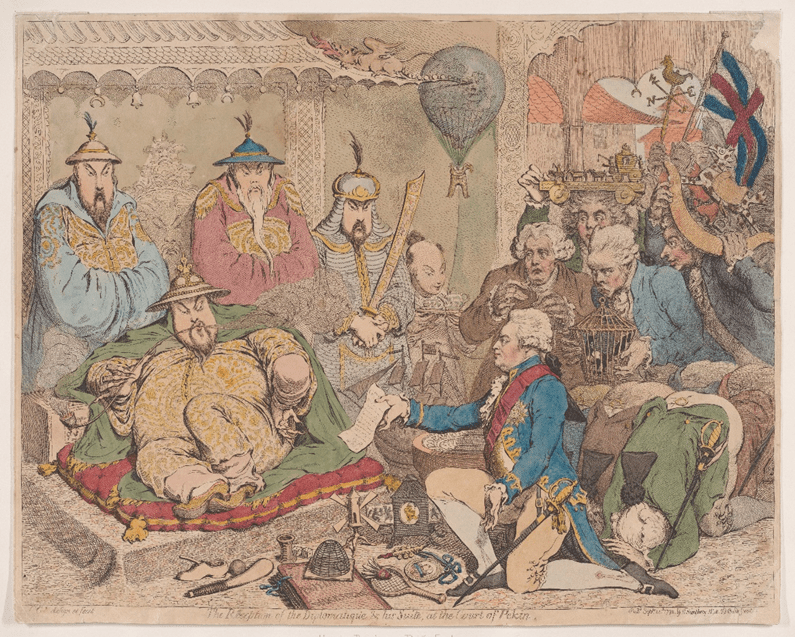

To illustrate how China treated foreigners or “barbarians,” according to some Chinese texts, it is essential to recall the first British attempt to establish a permanent embassy in China and negotiate free trade and equal relations. George Macartney, the head of the diplomatic mission, intended to convince the Chinese Emperor of China’s backwardness compared to Britain, where the industrial revolution provided numerous economic benefits. However, the diplomatic mission proved unsuccessful due to significant gaps in perceptions. In the eyes of the Emperor, the British people were seen as arrogant and uninformed barbarians seeking special favors. China perceives itself as superior to others, especially regarding culture, political system, and values. Interestingly, even the name of the country 中國, “Zhōngguó” could be interpreted differently – “Middle,” “Central Country,” or “Middle Kingdom” as the country was named during specific periods, implying its special role and being the center of the world. While this perception is accurate, China has been trying to advocate and popularize these ideas in a non-violent and peaceful manner, acknowledging their universal nature. In China’s version of exceptionalism, China did not export its ideas but allowed others to seek them.

James Gillray, September 14, 1792. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1917.

This sense of being a unique nation, or in other words, Chinese exceptionalism, still exists in the strategic thought of Chinese leaders. China has persistently maintained a high level of influence and sought to convince its neighboring countries to accept its role in the world, despite historical ups and downs and moments of division. According to traditional Chinese beliefs, history follows a cyclical pattern of decline and correction, and humans cannot fully control it. The optimal course of action is to strive for harmony with nature and the world. Chinese diplomacy aims to achieve “Great Harmony,” or, putting it differently, harmonious international relations, primarily seeking a world free of wars and conflicts.

Chinese philosophy and culture have shaped the vision of generations of Chinese leaders, with terms such as “peace,” “harmony,” and “harmonious world” present in the discourse of many political figures in China. Maintaining stability and development, both domestically and internationally, has become a primary task for China. China’s self-perception is represented by a sense of exceptionalism and a belief in its unique cultural values and political system. China views its peaceful rise as a distinct power, providing it with the natural right to promote just international relations and equality by safeguarding norms and principles such as non-interference in internal affairs and respect for sovereignty.

China’s world vision may appear cosmopolitan and overly idealistic to many observers. However, this self-perception of China, its role, and its vision of external affairs aligns, albeit with various contradictions, with Chinese-interpreted principles of realpolitik, such as those espoused by military strategist and philosopher Sun Tzu.

The role of peacemaking in China’s traditional foreign policy concept

To avoid delving too deeply into Chinese philosophy and traditions, which are genuine sources for understanding Chinese behavior, let us examine several principles China has pursued since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. As mentioned earlier, China presents itself as a pragmatic and peace-loving country, with “peace” deeply rooted in Chinese discourse for a significant period. China raised the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence in a joint Sino-Indian agreement in 1953. These principles include mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty, mutual non-aggression, mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality, and mutual benefit. These principles have played a significant role in promoting China’s vision of international relations and have been valuable in pursuing China’s foreign policy goals beyond its borders. These principles highlight the continuity of Chinese thought and align well with building a just and prosperous world, attracting many developing nations and striving to eliminate inequality.

China now presents itself as a peace-loving country that has not been involved in imperial wars and never initiated conflicts, aiming to contribute to the world through peacemaking. Indeed, there seems to be a contradiction when examining China’s track record of foreign military interventions, such as its participation in the Korean War in 1953 and the Vietnam War in 1979. The invasion of Tibet and the continuous display of aggression concerning disputed territories in the South China Sea and Taiwan further underscore this inconsistency. However, Chinese leaders maintain the perception that Beijing’s role in present-day international affairs is that of a guardian of peace, non-interference, and multilateralism. Throughout China’s rise and development, other foreign policy principles have been added to reinforce and complement the existing ones.

One of the critical foreign policy concepts was suggested by Deng Xiaoping and formulated between 1989 and 1991. The saying “韬光养晦” (Tāoguāngyǎnghuì) can be translated as “hide one’s capabilities and bide one’s time” or “keep a low profile.” The concept that dominated Chinese foreign policy for decades suggests that China should adopt a low-key and cautious approach to its foreign relations, notably regarding projecting its military, economic, and political power on the global stage. It emphasizes the importance of avoiding conflicts and confrontations that could impede China’s domestic development and stability. The underlying idea is that by maintaining a relatively low profile, China can focus on its internal development and economic growth while avoiding unnecessary friction or provocation with other nations. This approach seeks to minimize external interference, protect China’s sovereignty, and create a favorable international environment conducive to economic and social progress. However, it is essential to note that the “keep a low profile” approach does not imply complete passivity or isolationism. It recognizes that China should actively engage with the international community while aligning with its national interests and long-term strategic goals.

In this light, Hu Jintao, the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party from 2002 to 2012, pursued a policy course known as “China’s peaceful rise.” The concept of China’s peaceful rise emerged as a response to concerns among the international community regarding China’s growing economic and military power. It aimed to alleviate fears and promote a positive image of China’s rise as a responsible global player. The chosen policy direction focused on various aspects of China’s rise and encompassed several principles related to foreign policy:

- Peaceful Development: China commits to peaceful means in pursuing its development goals, avoiding hegemony and threats to other nations’ security while promoting international stability and cooperation.

- Mutual Benefit and Win-Win Cooperation: China advocates mutually beneficial relationships, equality, non-interference, and shared economic development in building partnerships with other countries.

- Harmonious World: China strives for a harmonious world order through peaceful coexistence, dialogue, and respect for diversity, emphasizing diplomacy, multilateralism, and peaceful dispute resolution.

Xi Jinping’s foreign policy as a paradigm shift

The guiding principles of China’s foreign policy depend on the international context, the domestic situation, and the leader’s personality. It is crucial to mention that China’s foreign policy entered a new era with Xi Jinping coming into power. While preserving most of China’s foreign policy principles, Xi sought to make China a more active player and assume greater responsibilities.

Under Xi Jinping’s leadership, China’s diplomacy has undergone significant transformations in a relatively short five years. Unlike his predecessors, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, who primarily focused on domestic issues during their initial terms, Xi has been actively engaged in foreign affairs. Xi Jinping advocates for “Major Country Diplomacy” (avoiding the negative connotation of “Great Power” and stressing that China is not seeking hegemony).

Xi’s ambitious foreign policy represents a paradigm shift from Deng’s low-profile diplomacy, which is irrelevant in the context of major-country diplomacy. China must pursue diplomacy that goes beyond the conventional norms of a typical major country and incorporates “Chinese characteristics.” Xi Jinping’s evolving perception of China’s position in the international system is paramount. While previous Chinese leaders, starting from Mao, generally viewed China as being on the periphery or semi-periphery of the Western-dominated international system, Xi holds a different belief. He asserts that China has shifted from the periphery or semi-periphery and has now positioned itself at the center. Xi explicitly states that China is “closer than ever to the center of the global stage” and “closer than ever to fulfilling the Chinese dream of national renewal.”

Xi Jinping is committed to strengthening China’s influence in the discourse on international relations. From the “China dream” (national rejuvenation) and the “community of common destiny of mankind” to the concept of a “new type of major country relations” and “win-win cooperation,” Xi Jinping is determined to introduce Chinese concepts and ideas into global discussions on world affairs. While some analysts argue that Xi prioritizes foreign policy and political issues over economic ones, it is important to note that they are often intertwined.

“Win-win cooperation” remains a cornerstone of China’s foreign policy today. Wang Yi, a top Chinese diplomat who summarized Xi Jinping’s views on justice and win-win cooperation, stated, “Rather than one side winning and another losing, both must be winners. We are duty-bound to do all we can to assist poor nations. Sometimes, we must prioritize ethics and justice over our interests; sometimes, we must forfeit our interests for the sake of ethics and justice. We must never pursue our interests alone or think only in terms of gain and loss.”

The concepts and principles presented above show how China and its leaders offer a different vision of international relations and the role China aims to play in it. Based on these principles, it is evident that China’s behavior regarding the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its willingness to participate in the peace process and act as a mediator aligns with the principles mentioned earlier, albeit with some inconsistencies.

The Chinese “Peace Plan”: Better Late Than Never?

Amid substantial pressure from the West and reputational damage to Beijing’s international image regarding its stance on the war, China decided it was time to take action. On the anniversary of the full-scale Russian invasion in February, China presented a 12-point position on the “political settlement of the Ukraine crisis.” However, some observers mistakenly labeled China’s position as a “peace plan,” which is far from reality. This position raised further questions and concerns due to its vague and abstract list of principles that China is standing on. Most of the points align with the Chinese foreign policy and diplomacy principles mentioned earlier. However, without providing concrete and detailed suggestions to ensure a just peace, the Chinese position, which is not a plan, reminds us of the Minsk agreements of 2014-2015 that yielded no tangible results. The position lacks a sequence of actions, leaves the role of parties ill-determined, and fails to criticize the Russian invasion. It also needs to address the role China could play in achieving lasting peace, aside from stating its readiness to participate in post-war reconstruction. The language used in the document raises questions as it refuses to label the Russian invasion as a “war” and instead refers to it as a “crisis.”

Revealing genuine motivation behind China’s position

Given the gaps in the released document, one could assume that China is testing the ground and checking the international community’s reactions. In fact, Beijing has nothing to lose, as it had hesitated for too long. The re-election of Xi Jinping for an unprecedented third term and China’s willingness to assume a greater role in international affairs could explain why China has initiated this charm offensive.

Against the backdrop of the recently negotiated rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia, where China played the role of mediator, it boosted Beijing’s confidence in arranging and facilitating peace talks between Ukraine and Russia. In essence, China’s position allows Beijing to remain vague, continue building relations with Moscow, and still claim to have voiced its position. It seems that China is trying to sit on two chairs simultaneously. By referring to the principles of sovereignty and territorial integrity, China attempts to please Ukraine, which seeks to regain control over the occupied territories by Russia. On the other hand, by discussing the “legitimate security concerns of all countries,” China is, in fact, justifying the Russian invasion.

The rhetoric used in the document, such as “abandoning Cold War mentality,” “expanding military blocs,” and “avoiding fanning the flames,” aligns with the traditional rhetoric used by China and Russia to counter the United States and the liberal international order ideologically. By referencing the Cold War mentality and blocs, China demonstrates its concerns, particularly regarding its rivalry with the US. While China may compete with the United States economically and militarily, it lacks one crucial element — alliance networks.

The United States has successfully built networks of reliable and trustworthy partners, such as the QUAD (Australia, India, Japan, US) and AUKUS (Australia, UK, US), which aim to deter potential aggression from Beijing in the Indo-Pacific. Furthermore, as mentioned in the document, China’s opposition to “unilateral sanctions” without authorization from the United Nations Security Council indicates China’s sensitivity to anti-Russian sanctions and the West’s determination to confront aggressors. If China were to invade Taiwan, Beijing would face the same fate as Moscow. This point in the document does not enhance China’s international image and questions its credibility as a peace broker and independent third party, as China provides diplomatic support for Russia in the UN and calls for the lifting of sanctions as a means to protect itself.

Therefore, it is crucial to note that China’s position on the Russian war against Ukraine is not solely about Russia and Ukraine. It revolves around the model of international relations, international order, and principles that China aims to defend. By framing the war between Russia and Ukraine as a conflict between NATO-Russia, US-Russia, and others, the recipients of China’s position are not only Kyiv and Moscow but also countries in other regions. The Chinese proposals should be viewed through the lens of Beijing, which strives to balance its relations between Russia and the West, as both are of crucial importance for China’s development and its growing role in international affairs. Despite ideological divergences, China’s deep integration into the global economy and export-oriented economic model necessitates maintaining stable relations with the West. By promoting its vision and principles in the document, Beijing is appealing to the Global South, which interprets the Russo-Ukrainian conflict in its own way, pursues its own interests, and seeks to balance American influence.

As Sino-American relations develop in a confrontational spirit across various domains, and with the recent spy balloon incident indicating a worsening situation, Beijing needs to gain the support of the Global South. Europe and the EU are also recipients of this position, evident from the geography of visits by Chinese former foreign minister Wang Yi, including France, Italy, Germany, Hungary, and discussions on the Chinese position at the Munich Security Conference with foreign ministers of Austria, Belgium, Ireland, Netherlands, the UK, and Ukraine, along with High Representative Josep Borrell. Given that relations between China and the EU are cooling and China’s image is harmed, China is interested in leveraging the EU’s strategic autonomy concept, allowing Brussels to balance its relations with Washington and develop ties with Beijing. The PRC attempts to distance itself from Russia by reiterating its peace and political settlement support. However, it does not convince European countries, as exemplified by Italy signaling its readiness to exit China’s BRI initiative, Lithuania adopting a hard line on Beijing, and overall support from EU members to reduce dependency on Russia and China.

International perception of the Chinese “peace plan”

The international reaction to China’s position varied. Russia officially welcomed China’s diplomatic activity, claiming support for China’s desire to resolve the conflict politically. However, Russia added that this should be done by acknowledging “new territorial realities,” which is not a good starting point for China and is unacceptable for Ukraine. Despite its official rhetoric, the Kremlin appears furious about China attempting to end the war without involving them. China and Russia are different countries with different national interests that only sometimes align. Hence, I would not characterize the Russia-China partnership as an alliance but rather a “political marriage of convenience.” China’s foreign policy is pragmatic. The war has provided China with important information on the capabilities and determination of other countries and pushed Russia into China’s embrace. Yet, if China seeks to use the Kremlin as an ally, it must halt the war until Russia faces unconditional surrender on the battlefield in Ukraine and until the Russian political system collapses. Regarding Ukraine’s evaluation, Kyiv responded cautiously to the Chinese position but identified points in the paper that could be discussed in detail. Of particular note is China’s decision to appoint Li Hui, an experienced Chinese diplomat with extensive knowledge of Russia, who served as a diplomat in China’s Embassy in the Soviet Union and as an ambassador to Russia. This appointment could play a significant role in further communicating China’s position and discussing concrete and detailed suggestions in Ukraine’s interests if China is genuinely willing to act as a mediator.

Speaking about the reactions from the West, it is noteworthy that many politicians view China’s expressed desire to mediate as a positive step. However, they doubt China’s true intentions and are concerned about various aspects of the published documents. Starting with the US, Jake Sullivan, National Security Advisor in the Biden Administration, criticized China, stating that the plan could be summarized by its first point, emphasizing respect for all nations’ sovereignty. He further added, “Ukraine wasn’t attacking Russia. NATO wasn’t attacking Russia. The United States wasn’t attacking Russia. This was a war of choice waged by Putin.”

Source: European Union, 2023.

The European Commission also criticized China’s 12-point plan to end Russia’s invasion of Ukraine as “selective” and based on misplaced ideas of security interests. The Commission pointed out that the Chinese plan is a political initiative grounded in an interpretation of international law that appears biased and may be seen as a justification for Russia’s aggressive actions. President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, believes that the Chinese document should be viewed in a broader context, as she states, “You have to see them against a specific backdrop. And that is the backdrop that China has taken sides by signing an unlimited friendship right before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine started.” NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg mentioned that China’s credibility had been questioned due to its failure to condemn the illegal invasion of Ukraine. This hesitation has contributed to a negative perception of China in the international community.

Can China Bridge the Divide? Assessing its Mediation Prospects in the Russia War against Ukraine

Based on the factors mentioned above, the position of China as a mediator between Ukraine and Russia is questionable for two reasons: its hesitation and lack of credibility. The two-faced moves of Beijing and the path of complicated balancing it has chosen will require time to rebuild trust and reputation. However, the main problem in mediating the peaceful settlement of the war does not lie in how China uses diplomacy or projects its influence and power. Firstly, neither side of the conflict has shown signs of negotiating readiness. Russia has taken various actions to make negotiations unfavorable, such as organizing sham referenda, amending the constitution, accepting “new subjects of the Russian Federation,” and committing war crimes and killing civilians. Ukraine has no choice but to fight until the last Russian soldier leaves Ukraine’s internationally recognized territories.

Additionally, China has limited influence on Russia and Putin. While Moscow depends on China to maintain economic stability, even in the face of sanctions, this does not constrain Putin’s actions aimed at using blackmail against other countries. For instance, Russia’s decision to station tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus shortly after Xi Jinping visited Moscow, where Russia and China issued a joint statement to refrain from escalating moves, raises concerns.

China’s willingness to be a mediator could be seen as a significant step in assuming the responsibility it seeks, aligned with its self-perception as a “major country.” However, it is worth noting that China’s limited involvement in conflicts as a mediator over the years has also sparked discussions. It is only now, under the leadership of Xi Jinping, that China is finally deviating from the principles formulated by Deng Xiaoping. Keeping a low profile is no longer a valid strategy, and Beijing is ready to participate more actively in international affairs. However, China’s endeavor to position itself as a mediator for peace is primarily driven by the prevailing global context, encompassing factors like the Sino-American rivalry and the broader political polarization. When examining China’s mediation experiences, most have occurred in turbulent conflict cases, and it cannot be claimed that they have yielded the desired results. For example, the recent mediation to resume diplomatic relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia, portrayed by various media as a “great success achieved by Chinese mediation,” is not as significant as it may seem. China entered the final stage of negotiations between the two countries, which countries like Iraq and Oman had already mediated for several years. Furthermore, they agreed to see China as an agreement broker due to the geopolitical situation in the region, where the Middle East is becoming more autonomous after the US withdrawal from Afghanistan, and countries are eager to build a post-American security architecture by limiting American influence. Therefore, having China as a mediator is suitable for this reason.

However, it would be unwise to completely ignore China and remove it from the list of potential facilitators. While China lacks diplomatic experience in successfully mediating conflicts of such scale as the Russian war against Ukraine, it would be better to focus on small but decisive and concrete steps, given that negotiations are presently not being considered as an option. There are several areas where China’s participation would be welcomed, and diplomatic actions in these domains would align with China’s position paper, international law, and the interests of the broad set of actors in the international community.

These areas include:

- China could facilitate progress in releasing and exchanging prisoners of war (POWs). If Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates participated in one of the POW exchanges between Russia and Ukraine, there is no reason why China cannot do the same. Additionally, if China is willing to be more ambitious, Beijing could attempt to arrange an “all for all” swap between Russia and Ukraine.

- The return of thousands of forcibly deported Ukrainian children is another area where China’s involvement could be valuable. If China undertakes the responsibility to resolve this problem, it will undoubtedly receive support from the international community.

- China could consider expanding the “Grain Deal” scope by increasing the range of transported goods or facilitating a similar agreement. Alternatively, China could support efforts to unblock most of Ukraine’s seaports to restore trade and supply chains, taking inspiration from Turkey’s actions.

These are a few suggestions where China’s participation could be helpful. Overall, China’s successful mediation prospects will largely depend on how China proceeds with its position paper and develops clear and detailed proposals. China needs to convince Ukraine, Russia, and the international community that its mediation efforts are worth a try. The first phone call between Xi Jinping and Volodymyr Zelenskyi after the invasion and visits from the Chinese special envoy to Ukraine and Russia will likely shed some light on China’s specific actions. For now, China needs to continue pressuring Russia over its nuclear rhetoric. In conclusion, assessing China’s diplomatic successes is better done by measuring actions rather than words. It is not enough for China to merely talk the talk; they also need to walk the walk and follow their diplomatic principles.