3 MB

Key takeaways

- Russian air operations against Ukraine have turned NATO’s eastern flank into a zone of recurrent airspace violations, creating a structural gap between the intensity of the threat and the caution of collective responses.

- The pattern of “managed ambiguity” in handling drones and missiles — intercepts, protests, and reclassification of events as mere “incidents” — reflects deliberate efforts to avoid escalation but also keeps most cases below alliance crisis thresholds.

- Frontline states such as Poland, Romania, and Moldova bear disproportionate operational risk, prompting legal and procedural changes on interception, while more distant allies prioritize alliance unity and strict non-entry into Ukrainian airspace.

- NATO and EU instruments are converging on a model of “defensive integration without operational entry”: deeper sensor, training, and command coordination with Ukraine, but no shared authority to engage Russian assets over Ukrainian territory.

- This restraint functions as short-term risk management but gradually weakens deterrence by normalizing spillover and signaling to Moscow that carefully calibrated airspace pressure carries limited cost, especially as political fatigue in Europe grows.

- Over the medium term, continued incidents and potential diversion of U.S. attention to other theaters could force Europeans to choose between a more integrated airspace protection architecture with Ukraine or accepting higher strategic risk at their own borders.

Russian air operations against Ukraine have turned large parts of Europe into a de facto front line of contested airspace. Drones, cruise missiles, and military aircraft launched toward Ukrainian targets routinely pass close to, skirt, or spill over the borders of NATO member states, triggering intercepts, airspace closures, and diplomatic protests from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea and the High North. For frontline countries, these episodes are no longer anomalies but a recurring pattern that blurs the line between the war “in” Ukraine and the security of Europe as a whole.

Yet despite this accumulation of incidents, Europe’s collective response has remained cautious and fragmented. Governments have strengthened national air defences, expanded air policing missions, and increased support for Ukraine’s own air and missile defence, but have stopped short of adopting a truly joint model of airspace protection with Ukraine. Proposals for a partial “closure of the sky” or a shared European “air shield” resurface after major incidents, only to run into familiar concerns about escalation, legal authority, and alliance cohesion.

This paper examines how Russian aerial incursions are reshaping Europe’s security environment and what that means for the future of air defence cooperation with Ukraine.

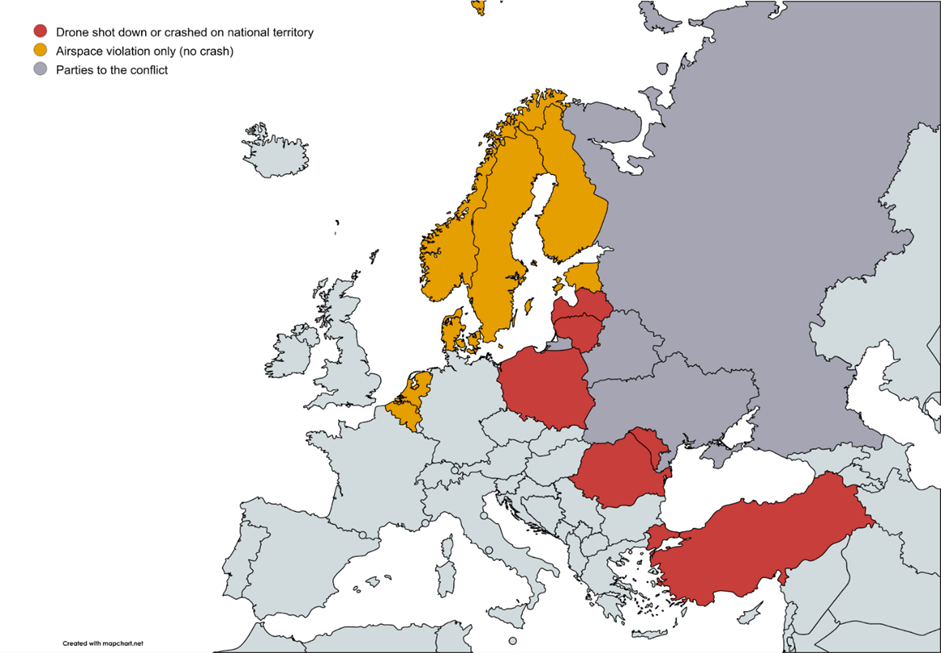

Mapping the Scope of Russian Aerial Incursions

Airspace tensions have become a defining feature of Europe’s security environment across multiple regions. On NATO’s eastern frontier, countries such as Poland, Romaniaа також в Baltic states regularly report drone intrusions, missile overflights, and unauthorized entries by Russian military aircraft-typically linked to strikes on nearby Ukrainian targets. In Northern Europe, Finland, Swedenта Norway have faced brief but deliberate airspace violations involving reconnaissance and fighter jets. The Black Sea region has seen Turkey intercept unidentified drones approaching from offshore, while Western European states, such as Belgium, have reported increased drone activity near strategic infrastructure. Beyond the Alliance, Moldova has experienced repeated cross-border incursions and debris fallout tied to Russian operations along Ukraine’s southern border. These varied incidents reflect a geographically dispersed but operationally connected challenge to the integrity of European airspace.

Heavily Affected European Countries

Countries closest to the war in Ukraine have experienced the most frequent and severe violations of their airspace by Russian military assets, but the exposure is not evenly distributed. Event-based monitoring suggests that Moldova and Romania together account for the vast majority of recorded spillover incidents along Ukraine’s western border corridor, which helps explain why both states have treated drone debris and cross-border intrusions as a persistent security problem rather than isolated accidents.

Poland remains a critical frontline case as well, not necessarily because it has the highest overall count, but because it has documented multiple high-profile incidents of Russian drones and missiles crossing into its territory, including the discovery of an undetected cruise missile deep inside its airspace and a mass drone incursion in 2025. These events have prompted live intercepts, NATO consultations, and formal diplomatic protests.

Moldova, though militarily neutral and outside NATO, has faced regular spillovers from Russian strikes against southwestern Ukraine. Russian drones and missiles have crossed Moldovan airspace or crashed on its territory on multiple occasions. Authorities have repeatedly closed airspace during active drone routes and summoned Russian diplomats to protest violations. Lacking its own air defense systems, the country has relied on airspace monitoring, diplomatic pressure, and international visibility to manage the threat, consistently framing these incursions as unacceptable risks to civilians and national sovereignty.

Romania has reported several cases of Russian drones breaching its airspace, particularly in the Danube region, with wreckage recovered on Romanian soil. Authorities have increased their air patrols and summoned Russian diplomats in response.

Turkey has intercepted Russian aircraft near its maritime borders and shot down a drone approaching from the Black Sea, framing its responses as firm but calibrated to avoid escalation. The Baltic states have faced recurring aircraft and drone incursions from Russia, including a multi-jet intrusion into Estonian airspace that prompted NATO consultations. In these frontline cases, governments have responded with heightened air patrols, updated interception laws та protocols, and calls for greater NATO engagement.

Moderately Affected European Countries

A broader group of European states has encountered Russian airspace violations with moderate frequency. This includes NATO members along the eastern and northern flanks – Finland, Sweden, Norway, as well as Turkey and Belgium. While these countries have not faced the same volume or severity as Romania or Moldova, their experiences reflect a clear pattern of deliberate airspace pressure by Russia.

Finland та Sweden have recorded several brief violations, typically involving Russian military aircraft entering or skirting their airspace over the Baltic Sea. Both countries scrambled jets, issued public condemnations, and strengthened regional coordination.

Norway has reported rare but notable violations in the Arctic, reinforcing its readiness posture in the High North. Belgium has investigated suspected surveillance drone activity near military installations and responded by increasing security and monitoring without attributing direct responsibility publicly

Across this wider group, states generally opt for a combination of military readiness and diplomatic restraint. Violations are documented and addressed through formal protest, interception, and regional cooperation, with the shared objective of upholding sovereign airspace without triggering escalation.

Non-European Countries Affected

Russian air provocations have not been confined to Europe. In East Asia, Japan and South Korea have frequently scrambled jets in response to Russian military aircraft entering or nearing their air defense zones. Japan has recorded direct airspace violations, including an incident in which its fighter jets fired warning flares to deter a Russian patrol plane. South Korea has also reported repeated Russian incursions into its air defense identification zone during joint Russian-Chinese military flights, and has responded with intercept missions and official protests.

In North America, the United States and Canada have tracked long-range Russian bombers and reconnaissance aircraft approaching their Arctic airspace. While most of these flights remained just outside national borders, they required intercepts from NORAD jets and reaffirmed the need for continuous surveillance across the northern air defense perimeter.

These cases illustrate that Russia’s challenge to international air norms is not limited to its immediate neighborhood. From Europe to East Asia and North America, countries are responding with a mix of military vigilance, diplomatic engagement, and regional coordination aimed at deterring further violations and maintaining control over their skies.

Why “Weak” Responses Are Structurally Rational

European and NATO-aligned governments have reacted to Russia’s airspace violations with noticeably uneven intensity, and the variation is not random. It follows a fairly consistent geography of risk: the closer a country is to Russia and to the Ukrainian theater, the more it tends to treat intrusions as an immediate security problem rather than a diplomatic irritant. Yet even the most exposed states often appear cautious. What observers describe as “weakness” is usually not a lack of awareness; it is the structural difficulty of responding to airspace incidents in a way that remains both credible and safe.

The first constraint — real-time ambiguity. Many episodes unfold within minutes, and the object can be small, low flying, intermittently visible on radar, or affected by electronic warfare that distorts navigation and communications. In that window, decision makers rarely have complete certainty about what the object is, whether it is armed, whether it is malfunctioning or maneuvering intentionally, and where it will go next, so the incentive is to avoid an irreversible kinetic action based on incomplete information.

The second constraint — the operational trade-off of interception. Shooting down a target may reduce immediate risk, but it almost guarantees a secondary one. Debris will fall somewhere, and if it falls on the defender’s territory and causes damage or civilian harm, the political and legal burden shifts instantly to the defending state. That reality pushes governments toward tracking, shadowing, warning procedures, and engagement only under clearer conditions, because a technically successful intercept can still produce a domestic crisis that undermines public support for air defense policy.

The third constraint — escalation dynamics. Air defense is among the most direct military instruments available, and when the violator is Russia, governments tend to assume that a single shootdown could trigger a rapid chain of retaliation, counterclaims, and alliance pressure that outpaces diplomacy. Even if a broader response never materializes, the incident can harden political positions and reduce room for controlled de-escalation. Many states, therefore, prefer to preserve decision space rather than be pushed up an escalation ladder by a border episode.

The fourth constraint is alliance politics. NATO’s deterrent strength rests heavily on unity, and unity often requires responses that all allies can support despite different threat perceptions, legal cultures, and risk tolerances. This creates a structural bias toward standardized procedures, collective messaging, and actions that clearly fit within territorial defence. Such measures are easier to sustain politically and legally across the Alliance than dramatic unilateral moves that might expose internal divisions. Within this framework, frontline states facing repeated spillovers from strikes on Ukraine may push for tougher measures, while more distant allies tend to favor options that contain incidents without redefining thresholds for the entire Alliance.

Taken together, these constraints produce a managed ambiguity in which states react quickly and visibly, but often choose measures that reduce risk and preserve control, even when that looks insufficient to outside observers.

This is where the deliberate classification of many cases as “incidents” becomes important. Labeling an episode as an incident does not mean it is treated as harmless; it means it is treated as not meeting the political threshold for alliance escalation mechanisms. Romania’s handling of drone spillovers near the Danube has often followed this logic: public acknowledgement, condemnation, and defensive adjustments, while emphasizing that the events are a spillover from strikes on Ukraine rather than deliberate attacks on NATO territory. Poland’s response to the 2022 missile tragedy was guided by a similar concern: leaders acted seriously, but avoided triggering an alliance crisis once the event was assessed as not being a deliberate Russian strike on Poland.

NATO’s institutional language reinforces this compartmentalization because Article 4 consultations are politically meaningful and can, in their own right, become escalatory if used too frequently. The result is, again, a managed ambiguity: states may respond militarily in defensive ways, but rhetorically and procedurally keep many episodes below the level of a formal alliance emergency. Today, frontline states are more likely to press for consultations as violations become repeated or large-scale, while more distant allies tend to favor keeping the “incident” category as broad as possible, precisely to avoid a situation in which repeated gray-zone pressure forces hard choices.

The trend line across Europe is therefore mixed. On the one hand, repeated violations are pushing countries toward tougher rules, faster decision loops, and higher readiness, especially near the eastern flank. On the other hand, the longer the conflict lasts, the more political fatigue becomes a strategic variable. Governments face the accumulating costs of sustained alertness, defence spending trade-offs, economic pressures, and public exhaustion. Fatigue does not automatically lead to capitulation, but it does create incentives to prefer quieter management over dramatic confrontation, and it can widen the space for voices arguing that stability is worth making concessions.

In this context, a historical analogy remains politically powerful: Europe’s response to German aggression in 1938, particularly the policy of appeasement associated with the Munich Agreement. The situations are not identical. Today’s Europe has collective defence structures, nuclear deterrence, vastly different economic interdependence, and an active support effort for Ukraine that has no direct equivalent in the late 1930s. Still, appeasement was not just a moral failure; it was a strategic misreading that allowed an aggressor to learn that risk-taking would be rewardedта it shifted the eventual cost of resistance upward.

The practical takeaway is not that Europe is simply repeating 1938. It is that prolonged conflict can normalize abnormal behavior and produce incremental accommodation. When the primary instinct is to keep crises small, to label them incidents, and to avoid “provoking” the aggressor at almost any cost, the aggressor may interpret this as strategic space rather than restraint. Over time, that dynamic can harden the conflict, extend it, or make its eventual settlement more difficult, because weak or inconsistent reactions reduce deterrence and increase the incentive to keep testing the boundary.

These structurally cautious responses shape not only how states react to individual incidents, but also how far they are willing to go in changing the architecture of air defence around Ukraine. This becomes most visible in debates about whether parts of Ukrainian airspace should be placed under some form of external protection.

Prospects for a Partial Airspace Closure Over Ukraine

A partial closure of Ukrainian airspace – in practice a limited no-fly zone – remains unlikely in the medium term, not because the idea lacks operational logic, but because it would require a political mandate that most allies are not prepared to grant. From Kyiv’s perspective, the argument is consistent: stronger external support for air protection, whether framed as “closing the sky” or creating a protected corridor, would save civilian lives, limit damage to infrastructure, and reduce the chances that missiles or drones will deviate into neighbouring states. More effective interception over Ukraine should mean fewer cross-border incidents and debris fallouts on NATO territory.

Turning this into policy, however, forces governments to answer questions they prefer to keep theoretical: who has the legal authority to engage Russian targets, over which airspace, under what rules, and how retaliation would be handled. Those are precisely the decisions most governments want to avoid. That is why the limiting factor is political, not technical. Once enforcement shifts even partly into Ukrainian airspace, the line between support and direct participation becomes hard to defend.

Instead, allies are deepening defensive integration without crossing that line. Within the Ukraine Defense Contact Group, the Integrated Air and Missile Defense Coalition aligns contributions around shared priorities: systems and interceptors, but also training, sustainment, and long-term operability. NATO’s Security Assistance and Training for Ukraine (NSATU) coordinates training and the flow of assistance from Allied territory, improving coherence while explicitly staying out of Ukrainian airspace. The Prioritised Ukraine Requirements List (PURL) focuses funding and procurement on urgent capability packages. Together, these instruments push integration forward through organisation and resourcing, while leaving the operational boundary intact.

As this cooperation matures, interests are diverging more clearly between “states that suffer” and “states that decide”. Frontline countries, repeatedly exposed to spillover, see compressed warning times and rising domestic pressure, and tend to move from ad hoc monitoring toward standing rules, legal authorities, and routines built for recurrence. Larger Western European allies, by contrast, remain wary of anything that blurs the line between supporting Ukraine and directly fighting Russia. For Germany and France, in different ways, the priority is to prevent a NATO–Russia war, harden NATO’s perimeter, and help Ukraine defend itself, rather than extend NATO enforcement into Ukrainian airspace.

NATO and EU policies reflect this compromise. The Alliance strengthens Integrated Air and Missile Defence and air policing along the eastern flank, but frames these measures strictly as defence of Alliance territory. Cooperation with Ukraine grows through training, planning, equipment, and interoperability, while the formal position remains that NATO will not enforce Ukrainian airspace. The EU complements this with resilience, monitoring, and capability‑building rather than combat roles. The emerging model is defensive integration without operational entry: allies help Ukraine see earlier, coordinate faster, and intercept more effectively, while NATO itself avoids assuming legal responsibility for policing Ukrainian skies.

This restraint is often justified as deterrence through caution, but it also reflects a broader bet on time. Many European governments act on the assumption that Russia’s strategic focus will remain on Ukraine, and that the risk of a direct attack on NATO stays low as long as certain thresholds are not crossed. Incidents are therefore managed as technical and legal problems rather than as steps toward war. Underlying this is a belief that the conflict can be contained until Russia’s leadership, economic constraints, or strategic exhaustion create a more favourable moment for negotiation.

In that context, “partial airspace closure” remains politically attractive but strategically constrained. It promises fewer drones over Poland or Romania and fewer fragments falling on NATO territory, but only at the price of making NATO an operational actor in a war zone. For now, most European governments judge that price to be too high. They prefer a structure in which Ukraine receives more air defence systems, intelligence support, and interoperability, while NATO increases its own readiness on the border and improves its ability to manage incursions on Alliance territory – a form of risk management that prioritises avoiding immediate escalation, even if it leaves long-term deterrence only partially addressed.

Taken together, these choices point to a consistent preference for deeper integration without direct enforcement over Ukraine. Yet even within that boundary, governments still face practical decisions about how far joint air defence with Ukraine can go in the coming years.

NATO-Ukraine Air Defense Cooperation, Scenario-Based Analysis

Even though a fully fledged arrangement for joint airspace protection with Ukraine remains politically unlikely in the near term, the recurring pattern of Russian drones and missiles drifting toward NATO border areas prompts European governments to think in terms of feasible options rather than slogans.

In practice, what is often described as a “shared air shield” is not one single decision but a spectrum of possible measures, ranging from purely defensive reinforcement within NATO territory to steps that would approach direct involvement over Ukraine. If such a concept were ever to move from debate into policy, it would most plausibly take the form of incremental choices that preserve escalation control, legal clarity, and Alliance cohesion.

Those constraints narrow the menu, but they do not eliminate it. States that are repeatedly exposed to spillover, especially along the eastern flank, have strong incentives to reduce risk, raise predictability, and prevent border incidents from becoming routine. The scenarios below, therefore, map the practical changes that could occur if cooperation deepened – from measures that are already compatible with NATO’s current posture, through options that remain politically contentious, to those that are close to impossible under present conditions.

Realistic Scenarios

Scenario 1: Reinforced Border Shield

In this scenario, NATO allies strengthen air defence on the Alliance’s eastern flank to protect their own territory. In practice, this means more frequent air policing patrols, more surveillance flights, upgraded radars and alert systems, and more joint drills along the border. Elements of this are already visible in routine scrambling of fighters, persistent surveillance near the eastern flank, and periodic reinforcement packages when the threat level rises.

The political logic is straightforward: this approach keeps all detection, tracking, and any potential engagement decisions strictly within NATO sovereign airspace and territory, under national rules of engagement and NATO air policing procedures. It is legally simple because it is framed as routine territorial defence rather than operations over Ukraine, and it signals readiness without crossing the threshold into direct involvement in the war. The main limitation is cost and tempo: maintaining high readiness is expensive and strains personnel, but it remains the most politically acceptable option for the Alliance.

Scenario 2: Sensor and Command Integration with Ukraine

In this scenario, NATO and Ukraine deepen technical integration in early warning, tracking, and command processes, without giving NATO forces the authority to engage threats in Ukrainian airspace. The core is a shared air picture, faster data exchange, interoperable procedures, and better coordination of cues for Ukrainian air defences. The attraction is that it improves effectiveness without changing the legal boundary: Ukraine remains responsible for engagements over Ukraine, and NATO remains responsible for engagements over NATO territory.

This scenario is increasingly plausible because it fits the existing pattern of support, training, and interoperability, including Ukraine’s gradual adoption of NATO-compatible communications and situational awareness practices. The countries most inclined to push this forward are those closest to the risk – especially Poland, the Baltics, Romania, and the Nordics – because earlier detection and better tracking reduce spillover into their own airspace.

Unlikely Scenario

Scenario 3: Pre‑emptive Interception Before Border Crossings

This scenario implies intercepting Russian drones or missiles on their trajectory before they cross into NATO airspace, potentially while they are still over Ukraine. It can look technically rational, because an earlier intercept may reduce the chance of debris falling in populated NATO areas.

Politically and legally, however, it remains highly unlikely. It would require either operating weapons in or over Ukrainian territory, or adopting a standing doctrine that treats an approaching object as engageable before a formal border violation occurs. That crosses a major threshold because it can be interpreted as NATO taking direct action against Russian assets in the Ukrainian theatre. Even if a single country tried to do it unilaterally, it would raise alliance cohesion problems and create a pathway to direct NATO–Russia confrontation.

Nearly Impossible Scenario

Scenario 4: NATO‑Enforced Partial Airspace Protection Over Western Ukraine

This is a limited no-fly zone in substance, even if it is branded differently. NATO aircraft and/or NATO air defence systems would actively enforce protection over parts of Ukraine – for example, western regions – by engaging Russian drones, missiles, and potentially aircraft.

Under current conditions, this scenario is close to politically impossible because it would make NATO a direct combat actor. Enforcement is not symbolic; it would require actual engagements, and Russia would likely respond militarily or politically in ways that create rapid escalation. It also lacks a treaty basis comparable to NATO’s collective defence mandate, as Ukraine is not covered by Article 5. Operationally, it would require sustained resources and a clear escalation‑management plan that most governments do not want to own.

Conclusion

Europe’s security outlook is becoming more precarious as Russian aggression continues. Governments from Warsaw to Vilnius have voiced deep alarm after repeated airspace violations, yet many remain hesitant to build truly integrated defences with Ukraine. Even when a joint European air defence “shield” is discussed, most allies still prefer cooperation that strengthens Ukraine without merging command responsibility or creating obligations that could be read as direct participation in the war. The result is a patchwork response: eastern flank states push for faster, tighter coordination because the risk is immediate, while more distant capitals emphasise caution, alliance unity, and incremental steps.

That hesitation matters because the war is no longer a short emergency; it has become a structural condition. The longer the conflict continues, the more the question of shared airspace protection will shift from “controversial” to “unavoidable”. Sustained Russian pressure normalises a dangerous rhythm of incidents, raises the cost of permanent high alert, and gives Moscow repeated opportunities to test reactions at low risk. Over time, deterrence becomes less about one dramatic decision and more about whether Europe can maintain credible readiness without exhausting itself.

In that context, deeper integration – including a shared air picture, faster cross-border warning, interoperability standards, and coordinated air defence planning – would not only protect Ukraine. It would also reduce spillover risks for Poland, Romania, and the Baltic region, and strengthen NATO’s ability to manage escalation by improving decision speed and situational clarity. Prolonged restraint can therefore make stronger steps more necessary later, precisely because weak or uneven reactions encourage continued probing.

The wider global context only heightens the stakes. A serious crisis over Taiwan involving the United States and China would likely pull U.S. attention and resources toward the Indo-Pacific, forcing Europeans to carry a heavier share of deterrence and defence at home. Russia could seek to exploit that distraction by increasing pressure on Europe, betting that allied bandwidth and stockpiles are already strained. Even without direct coordination between adversaries, a simultaneous crisis in Asia would harden Europe’s trade‑offs, accelerating decisions on readiness, industrial capacity, and long‑term defence planning. The price of defending Europe would rise, and the margin for slow, fragmented policy would shrink.

In such conditions, “black days” for Europe become plausible – not only in the sense of higher risk and cost, but also of greater clarity. A harsher environment would be dangerous, yet it could strip away illusions and make alliance utility undeniable. If Europe is forced into that moment, the idea of a joint airspace protection model with Ukraine is likely to move from theoretical to practical – not necessarily as a formal no‑fly zone, but as a more integrated, interoperable, and collectively managed air defence architecture in which Ukraine is treated as a pillar of Europe’s air security rather than a separate battlefield at the continent’s edge.

The conclusion is, therefore, a warning with a concrete policy implication. Europe, and especially the states directly affected by Russian spillover, are right to be concerned, but caution cannot substitute for strategy. The longer the war lasts and the greater its cost, the more urgent the question of shared airspace protection will become. Munich in 1938 shows how dangerous it is to assume that limited concessions will cap an aggressor’s ambitions. Today, assuming that Russia will be satisfied with Ukraine while treating repeated violations as mere incidents risks repeating that pattern of miscalculation. Europe still has time to choose preparation over improvisation, and unity over fatigue. If it waits until the next crisis forces coherence, the eventual price is likely to be higher.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations with which the authors may be associated.

This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. It’s content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.