2 MB

Wichtigste Erkenntnisse

- The gradual reorientation of U.S. strategic priorities toward the Indo-Pacific signals a likely recalibration rather than a full withdrawal of American military commitments in Europe, reshaping NATO’s deterrence framework.

- A U.S. drawdown could expose structural weaknesses in Europe’s defense architecture, particularly in strategic airlift, ISR, refueling, and integrated air and missile defense — capabilities still heavily dependent on U.S. assets.

- Divergent threat perceptions between Eastern and Western Europe risk deepening intra-alliance divides, complicating burden-sharing and procurement coordination as defense spending rises unevenly across member states.

- Germany, France, and the United Kingdom are emerging as the core actors positioned to fill capability gaps, yet their leadership balance will depend on aligning industrial, operational, and political agendas under sustained fiscal pressure.

- A reduced U.S. footprint would accelerate Europe’s pursuit of strategic autonomy but also test the continent’s ability to maintain credible deterrence against Russia without a singular transatlantic anchor.

- The extent to which Washington’s realignment remains a tactical adjustment or evolves into a genuine strategic withdrawal will determine the future cohesion and credibility of the transatlantic alliance.

The reorientation of U.S. strategic priorities toward the Indo-Pacific has reshaped Washington’s approach to Europe. As competition with China intensifies, a gradual recalibration of American military presence and commitments on the European continent becomes increasingly likely. This shift raises questions not only about the future of NATO’s deterrence architecture but also about Europe’s capacity to assume greater responsibility for its own defense. In this evolving landscape, the challenge for European allies is twofold: to adapt to a potential redistribution of U.S. resources and to develop the industrial, operational, and political mechanisms necessary to sustain strategic stability on the continent.

Against this backdrop, the paper explores the implications of a potential partial U.S. withdrawal from Europe, assessing its political, military, and economic consequences, as well as the prospects for enhanced European defense cooperation and autonomy.

U.S. Posture and Commitments in Europe

One must see the partial withdrawal of US forces not only as a consequence of resource reallocation but also as a means of pressure to encourage European states to strengthen their own defense capabilities and increase their capacity to ensure regional security.

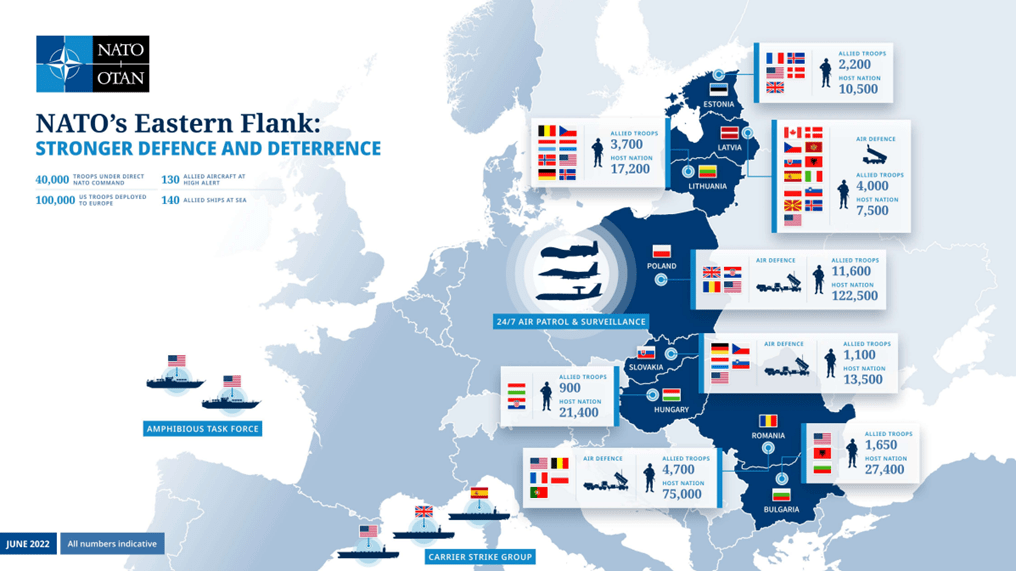

Currently, there are between 75,000 and 105,000 US military personnel stationed on the European continent, with most serving in the Air Force and Navy. In addition, the US has more than 40 military facilities of various levels, a significant number of armored vehicles, aircraft, multiple launch rocket systems, and about 100 tactical nuclear warheads deployed in Europe. Based on IISS estimates that direct US defense expenses in Europe account for roughly 5 to 6 percent of the US national defense budget, and applying that ratio to the FY2025 national defense topline of about 900 billion dollars, annual US costs related to European security are approximately 45 to 54 billion dollars, including funding for personnel, infrastructure, exercises, and joint programs.

A “partial withdrawal” means a reduction in the number of troops, infrastructure, equipment, and weapons. However, it is impossible to predict the scale and specific parameters of such a reduction at this stage. Under the current U.S. administration, decisions regarding the number of American troops in Europe may at times be influenced more by the President’s personal approach and the advice of his closest advisers than by recommendations from institutions such as the National Security Council or the Pentagon, as illustrated by the June 2025 decision to strike Iranian nuclear facilities without prior congressional approval.

A complete withdrawal would sharply weaken US influence over European countries and deprive Washington of important military and logistical bases and infrastructure, such as Ramstein Air Base in Germany and the Rota naval base in Spain, which play a key role not only for the European but also for the global US military presence.

Furthermore, a complete withdrawal of troops would inevitably undermine the trust of allies and cause a deep crisis in NATO, creating a strategic vacuum that Russia could exploit to expand its influence. Thus, despite the political rhetoric and the Trump administration’s desire to cut spending, the United States cannot afford to completely abandon its military presence in Europe.

At the same time, a second pathway cannot be excluded. Congress could frame a structured strategy through the annual defense authorization and appropriations process, directing the Department of Defense to rebalance force posture toward the Indo-Pacific while setting ceilings for permanent presence in Europe, replacing some rotations with prepositioned stocks, and conditioning drawdowns on allied capability gains and readiness benchmarks. Such a plan would likely phase changes over multiple budget cycles, require detailed reporting by the Pentagon and the NSC, protect key enablers such as airlift, refueling, ISR, and missile defense, and expand cost-sharing and joint procurement with European allies.

In practice, the president could still order a symbolic reduction of about 10 percent or a deeper cut of up to 50 percent on political grounds. Congress, by contrast, could codify posture changes in law, phase any drawdown over multiple budget cycles, link it to allied capability milestones, safeguard NATO Article 5, and shift forces and funding to higher priority theaters.

Strategic Consequences of a Partial Withdrawal

A partial withdrawal of the US from Europe will inevitably lead to a shift in the strategic balance of power on the Eurasian continent. Such a move will have mixed consequences: some countries will lose some of their strategic capabilities, while others will have the opportunity to strengthen their positions and expand their influence.

Politically, one of the most significant potential consequences is the fragmentation of NATO. A decline in US commitment could expose hidden fault lines within the alliance, leading to differences of opinion between Eastern and Western European members regarding threats. Eastern European countries directly threatened by Russian aggression may demand swift and decisive action. In contrast, Western European states may lean toward diplomatic solutions, undermining NATO cohesion and complicating collective responses. In addition, the emerging power vacuum could weaken regional deterrence, prompting Russia to escalate conventional and hybrid threats, including cyberattacks, disinformation campaigns, and covert operations to destabilize vulnerable states.

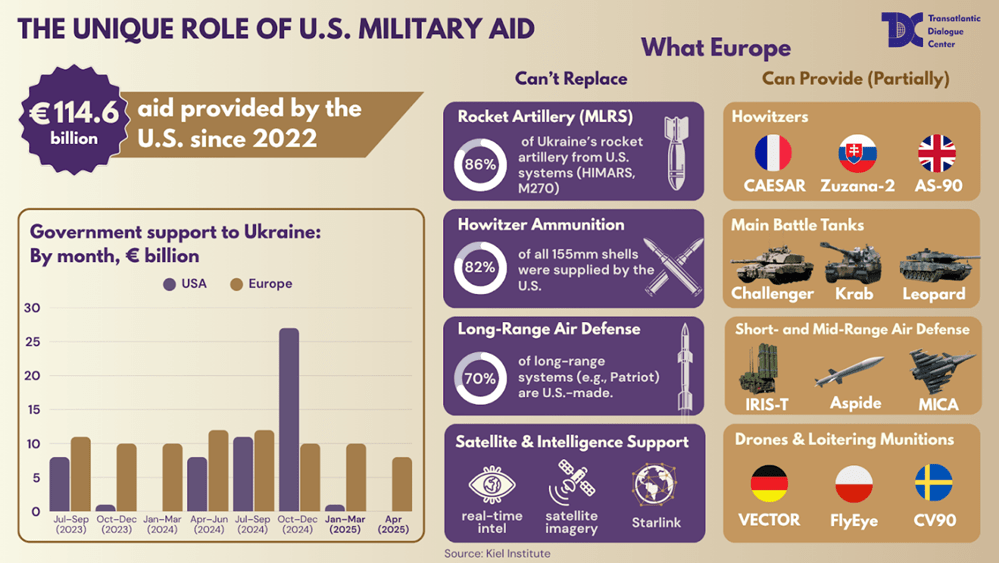

From a military perspective, Europe’s ability to effectively fill the gaps left by the partial withdrawal of US troops remains uncertain, despite recent initiatives such as the European Commission’s ReArm Europe Plan/Readiness 2030, which aim to strengthen defense procurement cooperation and enhance European strategic autonomy. European militaries continue to experience substantial capability gaps in key areas, such as strategic airlift, air refueling, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), and integrated air and missile defense systems – all areas traditionally supported by US capabilities.

The potential of the European defense industry to replace US forces and capabilities is promising but limited. Europe has a cutting-edge defense industrial base with major companies such as Rheinmetall, Airbus Defense, BAE Systems, Leonardo, and Dassault capable of producing complex weapons. However, significant barriers remain: a fragmented market that discourages cross-border buying, duplication across national programs, and limited surge capacity with long lead times for munitions and air-defence components. Accelerating joint defense procurement and industry consolidation, necessary to meet Europe’s security needs after the withdrawal of US troops, remains a challenge, although they are increasingly recognized as strategically necessary.

Economically, the US defense industry may initially benefit from increased short-term procurement in Europe aimed at addressing military capacity shortfalls, but will likely face market share losses as Europe develops its own alternatives. Politically, reduced involvement in European affairs could undermine US diplomatic influence around the world, weaken alliances, and negatively impact trade interests in a strategically important region.

Prospects for European Strategic Autonomy

In the event of a partial withdrawal of the United States from Europe, the following question naturally arises: who, and to what extent, is capable of filling the niche that would be created if such a scenario were to actually materialize?

As noted earlier, not all countries would suffer strategic losses in the event of a reduction in the US presence. Germany, France, the United Kingdom, and Italy appear to be the most likely candidates to play a key role in partially compensating for the decline in US influence, taking advantage of the situation to strengthen their own influence and expand their strategic capabilities. Germany has the necessary financial resources, human potential, technological capabilities, and, most importantly, the political will and a long planning horizon to implement multi-year programs. Berlin operates on binding medium-term financial frameworks, uses ring-fenced funds and multi-year procurement contracts, and aligns ministries and industry on capability roadmaps that extend into the early 2030s.

This setup lets Germany commit now to large, sequenced projects such as layered air and missile defense, a sustained munitions surge, integration of new combat aircraft, renewal of heavy land forces, and infrastructure for forward basing.

With the arrival of a new leadership headed by Friedrich Merz, Germany has significantly changed its military-political course, declaring its intention to become one of NATO’s mainstays on the European continent. As part of this strategy, Berlin plans to increase its military budget from the current 2.4% of GDP (about €95 billion) to 3.5% of GDP (about €162 billion) by 2029, which will be the largest expansion of defense spending in the history of modern Germany.

Another key contender for regional leadership alongside Germany is France, which has historically held a strong position in the European security architecture. In recent years, France has consistently contributed around 10% of NATO’s total budget, making it one of the Alliance’s main financial and military donors.

France’s unique position in Europe rests on its independent nuclear deterrent. With about 290 warheads on submarines and combat aircraft, Paris retains assured strike-back capability and signals a potential, limited nuclear umbrella for European partners, while keeping exclusive national control. This helps backstop any erosion of U.S. guarantees. Although the arsenal is smaller than that of Russia and the United States, continuous modernization sustains credibility and strengthens France’s role in burden-sharing debates.

The United Kingdom, which has the most powerful navy in the North Atlantic Alliance after the United States, is also considered one of the leading contenders for the role of potential leader in the European security architecture. London has officially announced its intention to increase defense spending to 5% of GDP by 2035, as has France, which should significantly strengthen its military capabilities and expand its presence in key strategic regions, including the North Atlantic and High North, the GIUK Gap, the Baltic and North Seas, the Mediterranean and Eastern Mediterranean, the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, and the wider Indo-Pacific, particularly the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. The UK’s status as a nuclear power remains an equally important factor: the country has approximately 225 nuclear warheads.

Italy has signaled ambition, planning to raise defence spending from 1.49% of GDP (≈€35 billion) to 2% (€46.8 billion) by 2025 and toward 5% (€117 billion) by 2035. Yet even with these targets, Italy’s military capabilities, industrial depth, and political weight still trail Germany, France, and the UK, making it a less likely candidate to anchor Europe’s security architecture in the near term.

Despite the allied agreement to raise defence spending, uneven progress will challenge alliance cohesion as a structural variable in collective security. Frontline states under direct Russian pressure may achieve the 5% benchmark earlier, while others will lag behind, reflecting differentiated threat perceptions and resource constraints. This divergence can intensify burden-sharing disputes, complicate force planning and basing as collective action problems, and provoke contestation over procurement and industrial policy – dynamics that may escalate into intra-alliance political conflict.

Prospective European Leadership Framework

No European country alone is capable of fully compensating for the possible weakening of the American presence. The most likely scenario might be the creation of a coalition of states most interested in maintaining stability and defense capabilities in the region. In practice, this coalition would likely include Germany, France, and the United Kingdom as the core, complemented by Eastern European and Baltic countries that are directly exposed to Russian threats.

These states, being the most vulnerable and motivated, would be the first to come forward with concrete security initiatives, assume leadership in developing new mechanisms of cooperation, and actively lobby for Europe’s strategic interests within NATO and the EU. The western part of the continent, in contrast, would play a more supportive role, contributing primarily through financial resources and political backing, but without the same urgency or direct involvement in operational planning. This division of roles would create a balance in which the “big three” and frontline states drive the agenda, while others reinforce it from the rear, ensuring that Europe as a whole maintains cohesion in the face of a reduced American presence.

Cooperation between these states will most likely be based on the principles of balance and mutual control, preventing any one power from dominating security issues. At the same time, the “big three” (Germany, France, and the UK) will take on leading strategic roles, given their economic, military, and technological capabilities.

However, this approach is fraught with a number of potential problems.

- First, there is a risk of internal divisions arising from different perceptions of threats, interests, and foreign policy priorities.

- Second, European countries face the need to significantly increase their defense spending, which causes political and social tensions in the context of limited budgetary resources.

- Third, the absence of a single leader, such as the US, may complicate operational decision-making in crisis situations, weakening Europe’s overall strategic effectiveness.

- Finally, a possible reduction in the US military presence could weaken the deterrent factor in relations with Russia, increasing the risk of destabilization on the eastern borders of the EU and NATO.

In this context, Ukraine will become the main assistant to the “big three,” since its unique experience in resisting Russia provides practical knowledge of modern warfare, resilience, and adaptation that are indispensable for strengthening the broader European security architecture. In this sense, Ukraine’s role is not limited to being a symbolic partner: it becomes a practical teacher whose battlefield-tested knowledge directly strengthens NATO’s collective resilience and the strategic stability of Europe as a whole.

In the long term, Europe’s ability to adapt to a potential U.S. drawdown will depend not only on individual states’ ambitions but on the institutional capacity of both NATO and the European Union to align priorities and resources. Rather than relying on one dominant leader, Europe’s strategic resilience will hinge on networked cooperation – through joint defense procurement, interoperability, and collective investment in technological innovation.

Conclusion

Considering all factors, a partial withdrawal of US troops from Europe is probable. The priority is shifting to the Indo-Pacific region due to China’s growing power and the risk of a crisis around Taiwan. Resources are limited by the budget, personnel shortages, and the burden on the defense industry, which requires long-term contracts and capacity expansion. At the same time, the US still needs extended nuclear deterrence, space and cyber capabilities, early warning, and maritime communications security in Europe, so it’s more about calibrating its presence than abandoning its alliance commitments.

The most likely scenario is a phased reduction of the permanent contingent with increased rotations and reliance on pre-positioning. The security burden will shift to the “big three.” The UK will fill the sea and underwater component, the projection of force by aircraft carrier groups, cyber and electronic warfare, and support the Black Sea and the North Atlantic. France will provide independent nuclear deterrence, readiness for expeditionary operations, air strike capabilities, and medium-range air defense. Germany is taking on heavy land forces, logistics, repair, and ammunition, as well as the deployment of layered air defense/missile defense in Central Europe.

The remaining allies are assigned niches in counter-UAV, close air defense, mine countermeasures, and anti-submarine warfare. Critical gaps that Europe must quickly fill include strategic air transport and refueling, ISR, integrated air defense/missile defense, sustainable ammunition stocks, and MRO capabilities. The US will retain the C4ISR framework, the nuclear umbrella, and its readiness for rapid reinforcement.

In the end, the question of how quick and deep the cuts will be is still up in the air. It is difficult to predict specific steps: the choice between symbolic cuts and more noticeable reductions will depend on developments in the Indo-Pacific region, Russia’s behavior, the willingness of Europeans to increase spending, and restrictions imposed by Congress, basic agreements, and NATO plans. The logic of the moment suggests evolution rather than a sharp break, with the US reducing its “heavy footprint” but retaining strategic functions, and Europe translating its ambitions into measurable combat readiness.

The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in the papers published on this site belong solely to the authors and not necessarily to the Transatlantic Dialogue Center, its committees, or its affiliated organizations. The papers are intended to stimulate dialogue and discussion and do not represent official policy positions of the Transatlantic Dialogue Center or any other organizations with which the authors may be associated.

This publication was compiled with the support of the International Renaissance Foundation. It’s content is the exclusive responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views of the International Renaissance Foundation.